Had fate decided otherwise, the many young pianists who died in the 1950s would have been the headliners of their generation. As it stands, these artists continue to command attention, albeit largely with their tragic early deaths as a defining characteristic of their fame. But in the case of these legends – Rosa Tamarkina, Dinu Lipatti, William Kapell, Richard Farrell, and others – they were already internationally admired for their masterful pianism and poised to continue on a trajectory of even more artistic triumphs and acclaim.

Had fate decided otherwise, the many young pianists who died in the 1950s would have been the headliners of their generation. As it stands, these artists continue to command attention, albeit largely with their tragic early deaths as a defining characteristic of their fame. But in the case of these legends – Rosa Tamarkina, Dinu Lipatti, William Kapell, Richard Farrell, and others – they were already internationally admired for their masterful pianism and poised to continue on a trajectory of even more artistic triumphs and acclaim.

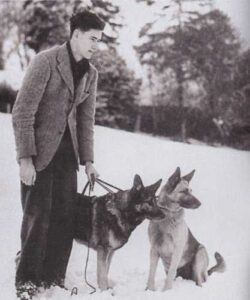

Another such pianist was Noel Mewton-Wood, who died by his own hand on December 4, 1953 at the age of 31. The young Australian had greatly impressed the cognoscenti of the musical world, playing in major centres with illustrious conductors. No less than Dame Myra Hess was awed by a performance he had given of Hindemith’s Ludus Tonalis when only 23: “The boy is truly remarkable – what he shall be like at 40-odd?” Legendary critic Sir Neville Cardus was also an admirer, after hearing him in Australia in 1945: “If Mewton-Wood can play the Diabelli Variations with this much authority today, how will he play them ten years hence?” Sadly, we would never find out.

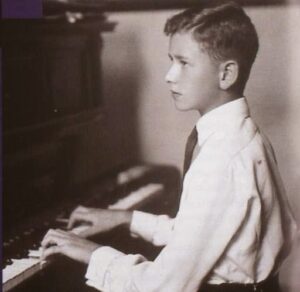

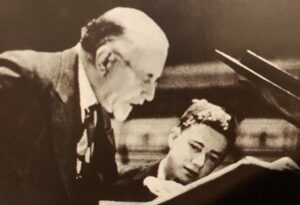

Noel Charles Victor Mewton-Wood was born November 20, 1922 in a suburb of Melbourne, Australia. His talent was cultivated by a mother who appears to have been quite a strong and determined character. The young boy took an entrance exam at the Melbourne Conservatory at the age of 7 when the minimum age was 15, and would be admitted on the condition that his mother no longer be responsible for his tuition. He studied there with Waldemar Seidel. The 8-year-old so impressed visiting legend Wilhelm Backhaus that a fund was created to enable him to study in Europe. He set sail for London, where he studied with Harold Craxton, and was later admitted to Artur Schnabel’s masterclasses in Lake Como.

Noel Charles Victor Mewton-Wood was born November 20, 1922 in a suburb of Melbourne, Australia. His talent was cultivated by a mother who appears to have been quite a strong and determined character. The young boy took an entrance exam at the Melbourne Conservatory at the age of 7 when the minimum age was 15, and would be admitted on the condition that his mother no longer be responsible for his tuition. He studied there with Waldemar Seidel. The 8-year-old so impressed visiting legend Wilhelm Backhaus that a fund was created to enable him to study in Europe. He set sail for London, where he studied with Harold Craxton, and was later admitted to Artur Schnabel’s masterclasses in Lake Como.

The young lad was apparently quite outspoken at a young age, not being afraid to be upfront even with the likes of both his teacher Schnabel and the great conductor Sir Thomas Beecham, who conducted his London debut in Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto on March 31, 1940. Mewton-Wood had auditioned for Beecham the year before at a Wigmore Hall session that lasted three and a half hours, leading the conductor to describe him as “the best talent I’ve discovered in the British Empire for years.” Their debut collaboration was attended by London’s musical elite, with no less than Sir Henry Wood stating that he was reminded of “all the great pianists of the past.”

Mewton-Wood played extensively in solo and chamber concerts (with violinists Josef Hassid and Ida Haendel, soprano Joan Hammond, and tenor Richard Tauber, among others), in addition to solo and concerto appearances. He toured his native Australia only once after his departure, in 1945, with later plans in the 1950s continually being pushed back in deference to the touring activities of other international pianists. He did regularly tour the UK – both as soloist and collaborative pianist – and also made tours of Europe, Turkey, and South Africa.

He was talented composer himself – he in fact hoped to focus all his attention on this in the future – Mewton-Wood was an exceptional interpreter of 20th century music, programming Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith, Busoni, and Prokofiev, collaborating with British composers Bliss and Britten: Bliss wrote his Piano Sonata for him and the Australian played Britten’s Piano Concerto with the composer on the podium (they premiered the revised version at the Cheltenham Festival on July 2, 1946), in addition to regularly accompanying his partner Peter Pears in performances of his songs.

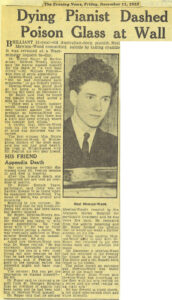

In late 1953, his partner William Fedrick – who had taken over management of his career – had complained of stomach pains, which Mewton-Wood did not take seriously due to his history of hypochondria. Alas, the situation this time was all too real: Fedrick had acute appendicitis and by the time he got to the hospital it was too late, and he died. The distraught pianist blamed himself for his lover’s death and attempted a suicide with an overdose of aspirin but was rescued by friends; he spent five days in psychiatric care and it was decided that he was no longer a suicide risk.

In late 1953, his partner William Fedrick – who had taken over management of his career – had complained of stomach pains, which Mewton-Wood did not take seriously due to his history of hypochondria. Alas, the situation this time was all too real: Fedrick had acute appendicitis and by the time he got to the hospital it was too late, and he died. The distraught pianist blamed himself for his lover’s death and attempted a suicide with an overdose of aspirin but was rescued by friends; he spent five days in psychiatric care and it was decided that he was no longer a suicide risk.

Sadly, this was not the case and his second attempt was successful. On December 4, 1953, after writing some 43 notes to friends, Mewton-Wood drank some cyanide he’d obtained from a lab in Cambridge. His doctor reported that spattered on the walls were the remains of the solution near a broken tumbler “which looked as thought it had been thrown against the wall.”

The Recordings

Mewton-Wood left a discography that is reasonably-sized given his early death, one which features more concerted works than solos: Beethoven’s 4th, the two Chopin, the Schumann, the three by Tchaikovsky (plus the Concert Fantasia), and some others. Many of these were available on 10-inch LPs on budget labels in the 1950s but few have been reissued since – the digital label Pristine Classical should be commended for having released remasterings of several of these accounts (click here) but a comprehensive edition has been lacking. A handful of broadcast recordings have been found and made available, though some remain unpublished and there are surely many more waiting to be located and issued. Below are but a sample of some of the artist’s commercial and broadcast performances.

Made when Mewton-Wood was about 19 years old, his first solo recordings – of Weber’s Sonatas 1 & 2 and the Chopin Tarantelle – find the young pianist playing with the qualities that would characterize his playing throughout his regrettably short life: beautiful tone, clear lines, rhythmic vitality, and attentive voicing.

Among Mewton-Wood’s first recordings from his 1941 sessions are a vivacious and heartfelt account of Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No.8 in G Major Op.30 No.3 with Ida Haendel. At age 19 his playing is notable not just for its technical brilliance – what tone, deft articulation, and mastery of pedal – but for the impeccable rapport with the violinist… truly collaborative music-making.

Here is a 78rpm-era account of the first edition of Schumann’s Etudes symphoniques Op.13 that was set down at three sessions at Decca’s West Hampstead Studios on December 15 & 16, 1948 and April 12, 1949 the earliest performance I’ve heard of the first edition. (You can hear a few major changes in the final movement; Raymond Lewenthal would play this version some time later but I had not been aware of Mewton-Wood having done so).

These 78s, made just as LPs were coming into use, capture his playing in fine fidelity despite the obvious crackle of the original discs and changes in acoustic discernible in parts recorded at different sessions. What an array of dynamic and tonal shadings, with impeccably poised voicing, deft articulation, and buoyant rhythm.

Here is Mewton-Wood’s distinguished reading of Chopin’s Piano Concerto No.2 with Walter Goehr conducting the Zurich Radio Orchestra, which circulated widely on a 10″ LP on the Musical Masterpiece Society that was part of many collections in the 1950s. Recorded when the pianist was not yet 30, the performance features marvellous playing, with elegantly crafted phrasing, a refined tonal palette, and intelligent use of rubato fused with dynamic and tonal adjustments.

A fine example of Mewton-Wood’s masterful collaborative work that also highlights his affinity with modern music is this account of the opening Song from Michel Tippet’s cycle The Heart’s Assurance. Tenor Peter Pears recalled that the Argo label recording was made “in a very curious manner somewhere on Park Lane in a basement. Very odd. But what came from Noel was [an] extraordinary radiance of performance. He could play the opening song of that cycle in a way which no one else has ever done again. The song rolled out and illuminated itself.”

This wonderfully vibrant 1953 reading of Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No.1 with the Concert Hall Symphony Orchestra conducted by Walter Goehr is the pianist’s last commercial recording. Mewton-Wood plays here with a strong rhythmic pulse, clear textures, and pronounced accents that do not sacrifice the quality of piano tone or break the line – a non-percussive yet energetic approach that is all too rare today.

There are not a large number of broadcast and concert recordings of Mewton-Wood that have been issued and it is to be hoped that more will become available. One that has is an absolute treasure: a truly magnificent January 1948 BBC studio performance of Busoni’s titanic Piano Concerto with Sir Thomas Beecham conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Men’s Chorus.

Aged merely 25 at the time, Mewton-Wood plays a with remarkable command of the instrument that helps him highlight large-scale dramatic nature of the work, with his refined tonal and dynamic control aided by marvellous pedal technique. What glistening tone in lyrical passages and incredible power at dramatic moments, without any compromise to phrasing and the quality of his sonority. And the pianist’s musical command is equally remarkable: this is a reading of astounding cohesiveness and maturity, and naturally Beecham is a more than capable partner in this superb performance!

To close, two BBC broadcasts from the pianist’s final year, the first in the Three Petrarch Sonnets by Liszt. His playing here is of the utmost refinement, with incredible dynamic control (how his pianissimos whisper!), sumptuous singing tone, flawless fusion of timing and nuance, and gorgeous phrasing. To my knowledge he commercially recorded only two of these three works, which makes the existence of this broadcast all the more wonderful. (It’s unfortunate that the announcer introduces each work individually rather than the three being played without a pause, but that’s just a small annoyance.)

This superb June 29, 1953 radio performance of Busoni’s Fantasia contrappuntistica that is a brilliant testament to the pianist’s glorious pianism. As in the Liszt broadcast, we can hear absolutely astounding dynamic control – what a feathery pianissimo (check out the section beginning around 6:10) – with truly beguiling singing tonal colours. His voicing, phrasing, and pedal technique are all skillfully employed to clarify Busoni’s wonderfully evocative composition. A masterful traversal!

Comments: 4

I may have left this comment at an earlier time, but I remember checking out a Westminster LP from a library of M-W playing one or both (?) of Busoni’s Violin Sonatas with violinist Max Rostal.

I think that the Busoni violin sonata performance is included in the ABC 3-cd Mewton-Wood set I have this set, but not right in front of me as I type.

The Rostal performance has just been reissued in a new box set devoted to the violinist on Eloquence

I have broadcasts of the Constant Lambert sonata, the Stravinsky Duo Concertante with Max Rostal. Also a copy of

a Joint Broadcast committee 78 of of him playing William Byrd–The Carmens whistle and Sellingers Round.

An interesting BBC Tribute talk too of about 40 minutes duration from Radio 3 around 30 or so years ago.

Happy to share if these are of interest.