There are many great pianists whose performing careers for a variety of reasons did not sustain the promise of their early years, and a good number of them became distinguished teachers whose influence on musical culture was still significant despite taking place behind closed doors. One such amazing pianist went from over 150 bookings a year in Europe before the war to an ever-dwindling number after having moved to Canada – in spite of rave reviews in major centres – yet her impact on the lives of countless students was profound. A distinguished and refined cultural icon, Lubka Kolessa taught generations of pianists who would go on to have notable careers in her adopted country and abroad.

There are many great pianists whose performing careers for a variety of reasons did not sustain the promise of their early years, and a good number of them became distinguished teachers whose influence on musical culture was still significant despite taking place behind closed doors. One such amazing pianist went from over 150 bookings a year in Europe before the war to an ever-dwindling number after having moved to Canada – in spite of rave reviews in major centres – yet her impact on the lives of countless students was profound. A distinguished and refined cultural icon, Lubka Kolessa taught generations of pianists who would go on to have notable careers in her adopted country and abroad.

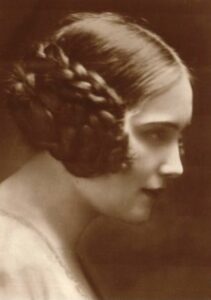

Lubka Kolessa was born into a musical family on May 19, 1902 in Lviv, Ukraine. Her first piano lessons were with her grandmother, who had trained with Chopin’s pupil Karol Mikuli, and once the family moved to Vienna she would study with Liszt’s protege Emil von Sauer. She won the Bösendorfer Prize at age 13 and well after graduation with an already active concert schedule she continued training with another Liszt pupil, Eugen d’Albert.

‘A Wonder’

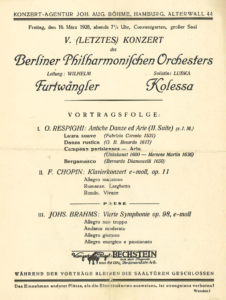

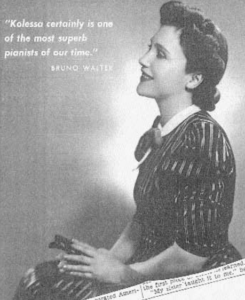

The conductors with whom she played in the 1920s and 30s reads like a Who’s Who of the legendary orchestral chiefs of the time: Furtwängler, Böhm, Keilberth, Strauss, Mengelberg, Walter, Wood, Weingartner, to name but a few. She apparently had to learn Liszt’s Second Concerto on 3 weeks’ notice when Furtwängler booked her when she was in her teens. She toured her native Ukraine in 1928 to great acclaim, and had several tours of North and South America that were equally successful (Rio de Janeiro’s A Noite stated that “the concerts of Lubka Kolessa were a great event in the world of art.”)

Kolessa made a British television appearance (wearing a traditional Ukrainian dress) on May 21, 1937 and that year played over 175 concerts, reviews brimming over with superlatives: “An artistic event of the first rank? No, more than that – a wonder!” That same year she would move to the UK as circumstances deteriorated on the continent. In Prague on March 13, 1939 – the eve of the occupation – she married James Edward Tracy Philipps, a British diplomat whom she had met on the Orient Express in 1936. Their son was born later in 1939, and with war having broken out in Europe, Philipps was assigned to Canada, the family arriving in Montreal in June 1940 (Philipps expressed strong displeasure with the Thomas Cook agency for having given them a second-class cabin).

Within the year Kolessa was booked to play with the Toronto Symphony, with the Globe and Mail review entitled “Kolessa’s Triumph” reporting that “No pianist of recent years roused more sincere and fervent expression of admiration,” adding that her performance “was a rendering that stirred every musical fibre in those who heard it.” She would teach at the Toronto Conservatory for 7 years starting in 1942, the beginning of a long teaching career in her adopted country (she appears to have parted ways with her husband by this time in what is said to have been a rancorous separation). In New York, she gave a Town Hall recital in April 1943 and in the following years she made a few appearances in which she shared the program, a 1944 appearance at the Ukrainian National Association Golden Jubilee Concert and two pops concerts in following years.

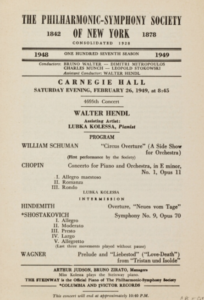

It was her January 27, 1948 recital at Carnegie Hall that generated particular attention. She played a massive program with a creative flow, Bach’s Toccata, Adagio and Fugue followed by Debussy’s Toccata, which led into Schumann’s Toccata and two works by Mozart; after intermission, a set of pieces by contemporary composer Arnold Walter was then followed by a group of Chopin Mazurkas that were bookended by the Fantasy and Andante Spianato and Polonaise. New York Times critic Harold Taubman was very impressed, calling her “a pianist of uncommon personality and charm…an artist with a heart and mind of her own,” and another headline read “Carnegie, where Kolessa belongs.” Thirteen months later she appeared with the New York Philharmonic to play Chopin’s E Minor Concerto and her recital the following year (April 3, 1950) was another massive programme: Schumann’s Etudes symphoniques, Mozart’s C Major Sonata, Liszt’s Funerailles, Paganini Etude No.4, and Hungarian Rhapsody No.12, two Scarlatti Sonatas, and Chopin’s B Minor Sonata.

Despite rave reviews, Kolessa’s career never reached the level it had in Europe and after a return visit to play and broadcast there in 1954, she withdrew from public performance to focus on teaching. She had by this point moved to Montreal (though she would also live in Toronto), where for the next two decades she taught at the Conservatoire de Musique du Québec, the École Vincent d’Indy, and at McGill University in Montreal. Among her pupils were the distinguished conductor and pianist Mario Bernardi (a mainstay on Canadian radio and concert platforms for decades), prize-winning pianist and teacher Louis-Philippe Pelletier, and renowned pianist-teachers Luba Zuk and Ireneus Zuk.

A supportive teacher

Kolessa appears to have been revered by her students, by whom she was referred to as ‘Madame Kolessa’ or ‘Madame K’. The esteemed Pelletier began studying with her when he was 15 and recalls that he was “very impressed, to say the least, by her personality, a mélange of calm authority and kindness. She accepted me in her class at The Montreal Conservatory and I gradually assimilated the basics of her wonderful technical approach. She was fluent in many languages (German, French, Italian, Spanish, Ukrainian) and very well-read. When I worked on the Dante Sonata, she urged me to go through the Divine Comédie, for instance. From time to time, at the end of a long day of teaching, she would invite me to play with her at one piano four-hands or two pianos the Mozart sonatas. She taught me the accentuation, articulation of phrases etc. This was for me a precious and unforgettable experience.” Pelletier adds that her repertoire covered a vast range: the complete Well-Tempered Clavier, all the Beethoven Sonatas (except for 106), the complete Mozart and Beethoven Concerti, and lots of Chopin, Brahms, Liszt, and Scarlatti.

An American pupil who in the 1970s traveled from New York to Toronto every two weeks to take lessons at Kolessa’s beautiful home in the affluent neighbourhood of Rosedale spoke glowingly about her encouraging approach to teaching and holistic music-making. Whereas other teachers tended to emphasize technique before focusing on tonal quality, with Kolessa it was the reverse: first came the focus on the sound so that the physiological actions would adapt in order to produce the desired sonority. Her linguistic aptitude supported her approach to music and she taught that understanding a composer’s language could help one understand the inflection and other details of their musical idiom: Kolessa stressed that precise notation for composers was not easy and that if you knew the language you would know how what to emphasize, how to breathe, how to phrase. To this end, she would speak in Hungarian to demonstrate an idiomatic approach to Bartok, German for Brahms, and so on.

Kolessa taught well into her old age and died in 1997 at 95. A scholarship in her name was created by some former students at McGill and it was only in the last decade or so that a collection of her recordings was made available on the DoReMi label out of Toronto. While some of the transfers were lacking in the full-bodied sonority that grace some of the master discs, this was an important revival of this great artist to the catalogue, bringing the name of a once idolized artist back to the awareness of collectors and piano fans.

Kolessa On Record

Kolessa made only a handful of studio recordings, all before 1950: a series of Ultraphone discs between 1928 and 1936 (some of them unreleased); a few more for Electrola, the German branch of HMV, mostly short solos and a single piano concerto; and two LPs for the Concert Hall Society in 1949. All of these have been issued on a 3-disc set on the Doremi label, together with a 1936 German broadcast of Mozart’s D Minor Concerto, making up her complete issued recorded legacy, though more broadcasts from her 1954 tour to Germany are known to exist. Regrettably the filtering on some of the older recordings leads a lot to be desired, but the playing is truly astounding, as the fresher transfers of some of these performances below demonstrate.

Kolessa’s sole studio concerto recording – her account of Beethoven’s Third Concerto with Karl Böhm conducting the Sächsische Staatskapelle – may be her only 78rpm-era recording to have been issued on LP. That June 1, 1939 Electrola reading – presented here from an excellent transfer for which I did the side-joins myself – captures her vivacious spirit and refined pianism with great fidelity. The playing is very much like Kolessa herself: refined, distinguished, but with impressive strength and backbone. There is always a full-bodied quality to her sonority regardless of dynamic level, and her nuancing and phrasing are elegant and poetic without the slightest hint of sentimentality or showmanship.

Kolessa’s recording of the Hummel Rondo in E-Flat seems to have been made in 1939 (details are not 100%) and was the ‘filler’ side for the 78rpm set (the Beethoven Concerto took 9 record sides, so the fifth disc had space for another piece). This terrifically clear transfer captures the sparkle, rhythmic vitality, deft articulation, and transparency of Kolessa’s playing with tremendous clarity.

Chopin figured prominently in Kolessa’s recitals, and her 1939 Electrola recording of the composer’s first Waltz in this excellent transfer captures the full-bodied sonority and elegant refinement of the Ukrainian pianist to perfection. Her timing is direct and simple yet elegant (particularly noteworthy are transitions), and her deft articulation is never at the expense of tonal beauty. Lines are elegantly crafted and there is a wonderful interplay between primary and secondary voices.

Kolessa also regularly featured Scarlatti Sonatas in her programmes, with this Sonata in B-Flat Major L.396 appearing to have been a particular favourite. Once again, we hear crisp articulation, gorgeous tone, and transparent textures, her sense of rhythm remarkably steady without ever being rigid.

As stated above, Kolessa made only two LP recordings prior to her 1954 retirement, one of Brahms and another of Schumann, for the Concert Hall Society label in 1949. The Schumann disc featured a glowing traversal of the Schumann Etudes symphoniques Opp.13 and posth and the Toccata Op.7. The Toccata had been featured in her 1948 Carnegie Hall recital while the larger opus was one of the key works in her 1950 recital. A digital LP transfer of the Schumann is currently being remastered and will be shared at a later date – in the meantime, here is the released transfer of Kolessa’s performance of the Etudes symphoniques, in which she incorporates the posthumous variations alongside the Op.13. Here too Kolessa demonstrates her fusion of refined elegance with strength and intelligence: textures are transparent, tone is beautiful at all dynamic levels, timing is natural, architecture and character wonderfully clarified.

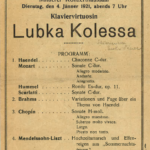

Kolessa played several large-scale works in her recitals, and the Brahms Handel Variations Op.24 that she put on disc is one that she had played at least as early as 1921 as per the concert programme reproduced here. As always, Kolessa plays with a combination of strength and elegance, with gorgeous tone, her mindful use of articulation shaping phrases and clarifying the diverse moods of each variation. Chords are impeccably voiced, dynamic levels skillfully layered, lines beautifully burnished, with some very interesting highlighting of left-hand voices often overlooked. A towering performance of this most challenging masterpiece that never never becomes overly weighty or a showpiece for the technical demands of the work.

Kolessa played several large-scale works in her recitals, and the Brahms Handel Variations Op.24 that she put on disc is one that she had played at least as early as 1921 as per the concert programme reproduced here. As always, Kolessa plays with a combination of strength and elegance, with gorgeous tone, her mindful use of articulation shaping phrases and clarifying the diverse moods of each variation. Chords are impeccably voiced, dynamic levels skillfully layered, lines beautifully burnished, with some very interesting highlighting of left-hand voices often overlooked. A towering performance of this most challenging masterpiece that never never becomes overly weighty or a showpiece for the technical demands of the work.

To close this tribute to this remarkable artist, the Brahms Intermezzo in C-Sharp Minor Op.117 No.3, played with just the right degree of mournfulness and at a spacious tempo in the outer sections without the textures becoming dense or phrasing losing shape, as often happens in contemporary readings of Brahms (the contrast with her briskly-paced middle section is quite remarkable). With beautifully burnished tone, masterfully forged lines, and impeccable timing – most notable at transitions, so often overlooked! – Kolessa reveals depth and emotion with elegance and intelligence, reflecting her true fullness of character and her noble career.

Sincerest thanks to The Brazilian Piano Institute, Rémy Louis, and Michael W for the wonderful concert programmes reproduced in this feature; to Louis-Philippe Pelletier and an anonymous (at her request) pupil of Kolessa for their precious testimonials about this great artist; and to Charles Timbrell and Jean-Pascal Hamelin for their introductions to Kolessa’s pupils.

One comment

BRAVO, MARK! You have done a wonderful presentation of her life, teaching, and recordings! I especially love her freedom in the Schumann Op. 13. Every phrase has character, warm romantic spirit, and love of contrasting sonorities and textures, without excessive point-making., big sound without percussiveness, and a really complete technique. She makes almost everyone else sound dull and frumpy by comparison, including (maybe especially) Myra Hess….