When I first started collecting records, Harold C Schonberg’s book The Great Pianists was my training manual. I dutifully read through it (more than once), making a list of names of pianists he recommended and revisiting his beautiful descriptions of their playing. In my regular jaunts to second-hand stores in my hometown of Montreal, I succeeded to find lots of LP reissues of historical recordings by artists mentioned in Schonberg’s tome and I listened attentively to their playing. One such artist of whom a single LP was produced – because that virtually all that he recorded – was the Russian pianist Josef Lhévinne.

When I first started collecting records, Harold C Schonberg’s book The Great Pianists was my training manual. I dutifully read through it (more than once), making a list of names of pianists he recommended and revisiting his beautiful descriptions of their playing. In my regular jaunts to second-hand stores in my hometown of Montreal, I succeeded to find lots of LP reissues of historical recordings by artists mentioned in Schonberg’s tome and I listened attentively to their playing. One such artist of whom a single LP was produced – because that virtually all that he recorded – was the Russian pianist Josef Lhévinne.

It didn’t take long for me to find several different pressings of Lhévinne’s recordings, as the hour’s worth of gems that he’d set down had been reissued many times over the years by the RCA label for whom he’d produced his handful of discs. Although all of the works were on the shorter side, the quality of the playing was evident and matched Schonberg’s descriptors perfectly: the author wrote of ‘the finish of his playing, his extraordinary technique and ease of delivery, his innate musicality’, adding that ‘his tone was like the morning stars singing together, his technique was flawless even measured against the fingers of Hofmann and Rachmaninoff, and his musicianship was sensitive.’

In 1988, a few years after I read the book and heard these recordings, Schonberg visited Montreal and gave a lecture-presentation in which he shared recordings by some of the great ‘golden age’ pianists, Lhévinne included. CDs had only just begun to be produced with some of these historical recordings, but overall these were far more difficult to access than they are today. The sound quality of his own recorded 78s on the sound system in the hall was extraordinary, and I remember him playing Lhévinne’s legendary 1928 account of the Schulz-Evler Arabesques on The Beautiful Blue Danube’ by Johann Strauss and being mesmerized by the playing.

Lhévinne’s recording has been so universally praised and played that many were and still are unaware that he played a truncated version of the transcription in order to fit the work onto the two sides of the 12-inch RCA 78rpm discs – this record should have allowed for up to 9 or 10 minutes of playing but Lhévinne plays it in 7, so why he played an abridged version is unclear and a great shame, as his playing of the opening figurations in the score would surely have been magnificent. This popular record was the Russian pianist’s first disc for RCA, set down on May 21, 1928, yet Lhévinne would not produce another recording until 1935 (more about his discography further down this tribute page).

Here is a wonderful transfer of that recording produced by Tom Jardine, to whom all thanks (for this and another transfer below) :

The LP reissues gave us little insight into Lhévinne’s life and character, and I never really picked up on a key line in Schonberg’s book that offered a glimpse into something rather important: ‘he contented himself with teaching, playing far fewer recitals than many pianists who were infinitely less gifted.’ What hadn’t struck me was that he was not particualrly displeased with not having a big career and that this might be part of why he produced so few records. His name having been spoken of so highly amongst fans of historical recordings – and his few recordings having been reissued so frequently – I assumed that he had a significant career, not that he actually lacked ambition and was satisfied not being so active; however, it appears that the latter scenario is the case and that it was his wife Rosina Lhévinne – herself an incredible pianist and teacher (who outlived him by more than three decades) – who pushed him to be more active.

The LP reissues gave us little insight into Lhévinne’s life and character, and I never really picked up on a key line in Schonberg’s book that offered a glimpse into something rather important: ‘he contented himself with teaching, playing far fewer recitals than many pianists who were infinitely less gifted.’ What hadn’t struck me was that he was not particualrly displeased with not having a big career and that this might be part of why he produced so few records. His name having been spoken of so highly amongst fans of historical recordings – and his few recordings having been reissued so frequently – I assumed that he had a significant career, not that he actually lacked ambition and was satisfied not being so active; however, it appears that the latter scenario is the case and that it was his wife Rosina Lhévinne – herself an incredible pianist and teacher (who outlived him by more than three decades) – who pushed him to be more active.

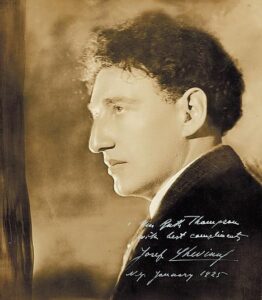

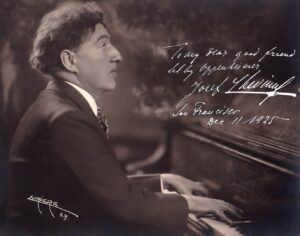

He certainly seemed destined for a career in music early on. Joseph Arkadievich Levin was born December 13, 1874, the ninth of eleven children in a musical family; he would later adopt the unconventional spelling Lhévinne from the more common Levin (and perhaps Josef from the original Joseph too) at the suggestion of a European manager. He showed signs of musical talent at a young age and he was clearly already adept when at age 11 he played at an event that was attended by Grand Duke Constantine, who expressed great interest in the child’s future and helped secure financing for his training in Moscow with Vassily Safonov.

His training progressed to the point that at age 14 he played for his idol Anton Rubinstein, who was greatly impressed. He was then invited to play at a golden jubilee concert in honour of Rubinstein, after which the legend invited him to play at a benefit event at which he would conduct him in Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto. He graduated from the Conservatory in 1892 at the top of a class that included Rachmaninoff and Scriabin. The 18-year-old spent that summer with Rubinstein, whose interest Lhévinne stated ‘was an inspiration to me and helped me more than anything could.’

His training progressed to the point that at age 14 he played for his idol Anton Rubinstein, who was greatly impressed. He was then invited to play at a golden jubilee concert in honour of Rubinstein, after which the legend invited him to play at a benefit event at which he would conduct him in Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto. He graduated from the Conservatory in 1892 at the top of a class that included Rachmaninoff and Scriabin. The 18-year-old spent that summer with Rubinstein, whose interest Lhévinne stated ‘was an inspiration to me and helped me more than anything could.’

His career was well and truly launched in 1895 when he won the Anton Rubinstein prize in Berlin, and the resulting initial tour saw success in Paris and Amsterdam before being interrupted due to compulsory military service. In 1898 he married Rosina – six years his junior and herself a gold medalist in her class in Moscow – and thus began a long personal and professional partnership. They moved to Berlin in 1907 and then to New York in 1919, where they would both become among the most famous (and longtime) teachers at Juilliard.

It has become more clear with the release of a handful of recordings of Rosina Lhévinne that she was an absolutely astounding pianist in her own right and it appears that she deliberately put her own performing career on hold as she attempted to get her husband to play more regularly and widely; they played as a two-pianist team both in recital and with orchestra but Rosina would otherwise avoid resuming solo performances until quite some time after he husband’s premature death. Josef did continue to play – making solo, chamber music, and concerto appearances – but it seems he did so far less than fans of historical recordings might assume given his legendary status to collectors. He died of a heart attack on December 2, 1944 – less than two weeks before his 70th birthday.

The Recordings

Josef Lhévinne’s sanctioned discography consists of about an hour’s worth of solo and duo recordings. These consist of four short solo works recorded with the acoustical (horn-based) recording process in December 1920 & January 1921 for French Pathé; solo recordings for RCA Victor set down in merely four sessions in 1928, 1935, and 1936; and two-piano recordings with Rosina. Only one of the duo performances was approved for release – Debussy’s Fêtes (arranged by Ravel) – which brought the total number of issued performances during his lifetime to one hour; however, after his death, the couple’s attempt at a Mozart Two-Piano Sonata was published, a significant addition of about 17 minutes to both artists’ meagre discographies.

Josef Lhévinne’s sanctioned discography consists of about an hour’s worth of solo and duo recordings. These consist of four short solo works recorded with the acoustical (horn-based) recording process in December 1920 & January 1921 for French Pathé; solo recordings for RCA Victor set down in merely four sessions in 1928, 1935, and 1936; and two-piano recordings with Rosina. Only one of the duo performances was approved for release – Debussy’s Fêtes (arranged by Ravel) – which brought the total number of issued performances during his lifetime to one hour; however, after his death, the couple’s attempt at a Mozart Two-Piano Sonata was published, a significant addition of about 17 minutes to both artists’ meagre discographies.

We are fortunately living at the most incredible time to enjoy recorded history, as in 2020 the amazing Marston label put out a three-disc set that includes not only the complete approved commercial recordings in the best transfers ever released but also a number of broadcast recordings; while airchecks of some shorter works had previously been available for a while (first on APR back in the early 1990s), these are now supplemented by some absolutely incredible discoveries previously unknown to even the most dedicated collectors, among them a nearly complete 1936 Tchaikovsky Concerto in wonderful sound (much better than the rather uninspired 1933 broadcast of the last two movements in constricted sound) and a vivacious 1942 broadcast of the Brahms Piano Quartet No.1 in absolutely incredible sound. The video below that I prepared for this phenomenal set (which is available here) includes some representative excerpts:

The pianist’s first efforts in the studio – four short solo works released on two French Pathé discs – are the most overlooked of his official discography, given their poor sound and their relative rarity, in no small part due the lack of a parent company who would release such a small volume of performances in the LP era, whereas RCA’s longevity led to Lhévinne’s studio discs for that company being regularly reissued. Despite their relatively faded and constricted sonic framework – a given due to the lack of microphone-captured sound in the recording process used at the time – the playing is superb, and one can appreciate Lhévinne’s subtlety of articulation, voicing, and pedalling in his account of his classmate Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in G Minor Op.23 No.5:

His recording of the Tchaikovsky Trepak Op.72 No.18 is all the more interesting when one considers that the pianist had met the composer by chance on the street in Moscow. Tchaikovsky asked Lhévinne if he would learn some of the works in the suite that contains the particular work on this early disc, and thehy planned to meet at a later date to discuss the score but unfortunately the composer died before returning to Moscow. Even with the faint sound of this early recording, we can hear some great intensity in Lhévinne’s playing, with a strong rhythm, deep sound, and crisp articulation.

The rest of Lhévinne’s official solo discography was set down in RCA’s studios, first in Camden (New Jersey) and then in New York. After the success of his May 1928 account of the Schulz-Evler Blue Danube paraphrase above, the pianist did not produce another record for seven years – whether it was a lack of ambition, economics, or something else (or a combination of these factors) – is unclear. In 1935 and 1936 Lhévinne had three more sessions for his solo recordings (June 7 & 10, 1935 and January 6, 1936) during which he set down performances of two works by Schumann and several by Chopin – all shorter compositions that fit on one or two sides of a 78rpm disc.

It is a great shame not only that he didn’t produce more records but that the works chosen were all so short; there’s no doubt that the playing is of great interest regardless, but knowing more about the pianist’s repertoire and capabilities makes one rightly long for more. Harold C Schonberg wrote about his legendary octave glissandi in the Brahms Paganini Variations, but unless a broadcast performance miraculously materializes, we will have to continue to imagine his combination of virtuosity and musicality in this treacherous passage and others in the repertoire. (Although Lhévinne did produce mechanized player-piano ‘rolls’ with some longer works, I have yet to hear a reproduction in this medium that accurately captures the crisply defined articulation, phrasing, pedalling, rhythmic pulse, and tonal palette that can be heard on his audio recordings.)

The playing that has been preserved on disc, however, is eminently worthy of attentive listening and appreciation. Lhévinne’s pianism is extraordinarily refined, the most immediately noticeable characteristic being the purity of his sonority and the phenomenally clear articulation and voicing of primary and secondary voices, regardless if played in the left or right hand. His rhythm is ironclad, yet his timing is anything but rigid, with wonderful yet restrained timing adjustments. In short, all is judiciously proportioned. If one were to find fault, it might be the lack of risk-taking or pushing the limits of creativity and imagination as one might hear in, say, Hofmann, Friedman, Barere, or others from that generation: the performances are so tasteful, clean, and ‘correct’ that they aren’t particularly revelatory in an interpretative sense. However, when it comes to a balance of pianistic refinement and musical taste, they are most certainly exquisite – he was a craftsman.

The playing that has been preserved on disc, however, is eminently worthy of attentive listening and appreciation. Lhévinne’s pianism is extraordinarily refined, the most immediately noticeable characteristic being the purity of his sonority and the phenomenally clear articulation and voicing of primary and secondary voices, regardless if played in the left or right hand. His rhythm is ironclad, yet his timing is anything but rigid, with wonderful yet restrained timing adjustments. In short, all is judiciously proportioned. If one were to find fault, it might be the lack of risk-taking or pushing the limits of creativity and imagination as one might hear in, say, Hofmann, Friedman, Barere, or others from that generation: the performances are so tasteful, clean, and ‘correct’ that they aren’t particularly revelatory in an interpretative sense. However, when it comes to a balance of pianistic refinement and musical taste, they are most certainly exquisite – he was a craftsman.

His June 7, 1935 disc of the Schumann Toccata in C Major Op.7 is considered by many to be a reference recording, not notable for its speed (which is rather modest) or flashy displays of virtuosity, but for its measured good taste, with clarity of legato melodic voicing and amazing transparency of texture throughout. Here is that record in yet another fine transfer provided by Tom Jardine:

The only other Schumann work we have on disc (recorded on the 2nd side of the Toccata 78rpm disc) is Liszt’s arrangement of the song Frühlingsnacht, which is astounding in so many ways: the incredible evenness and voicing of repeated figurations, the wonderful combination of dynamic variation and timing at the ends of phrases, and the beautiful tone throughout … all are exquisite. Two and a half minutes of magic, in a glorious new transfer by Tom Jardine:

All of the other solo records that Lhévinne produced are of shorter works by Chopin – would that we had Sonatas, Ballades, Scherzi, and the like, but the few Etudes and Preludes that he put on disc are, as all his performances, masterfully controlled and pianistically flawless. It is particularly worth noting how in a work like the Winter Wind Etude (the towering Etude in A Minor Op.25 No.11) he avoids overt attempts at speed and the loudest sound one might imagine; however, the tension brews from within as a result of his measured tempi, flawless voicing, and full-bodied singing tone at all dynamic levels – never a harsh sound. Here, yet again in a beautiful transfer by Tom Jardine, we can hear him play this Etude and two more, Op.10 No.11 (not Op.10 No.6 as listed on the record label shown in the video) and Op.25 No.6 from Victor disc 8868 … and if you listen closely you can hear Lhévinne singing along in the first few seconds of the Winter Wind!

In his final solo session of January 6, 1936, Lhévinne recorded a mere two Chopin Preludes – would that he had committed the entire set to disc! – but what glorious performances they are. In the Prelude No.17 in A-Flat Major below, long lines with lyrical phrasing, impeccable timing, and gorgeous tonal colours all make for a superb interpretation.

The longest Chopin work that Lhévinne recorded was the once-ubiquitous Polonaise No.6 in A-Flat Major Op.53, and this traversal of the work eschews the bombast and aggression that have often masqueraded as strength, power, and nobility in generations of pianists’ performances. Throughout we can experience his sumptuous jewel-like tone, masterfully voiced chords, steady but never boxy rhythm, and impressive dexterity – how those famous octaves are so light, clear, and consistent while the melodic content above is presented so transparently, and the left-hand lines that follow are also marvellously shaped.

While all the few solo broadcasts of Lhévinne that have surfaced regrettably duplicate repertoire from his studio recordings, there are important differences that indicate that as fine as the pianist’s officially released performances are, he could clearly be far more impassioned in public; this is the case with many artists, for whom the studio was not fully conducive to inspiring their most heart-felt playing. Particularly fascinating is a comparison of the A-Flat Major Polonaise: as beautiful, noble, and powerful as the 1936 studio recording above is, an aircheck from the previous year (shared below) is on a completely different plane. The November 3, 1935 broadcast performance account features a blazing intensity, strength and depth of tone, and impulse that are not evident in the more controlled yet still powerful studio account. It is hearing a live recording like this that we can better imagine the power that Lhévinne’s playing must have had in live performance. After the amusingly stilted introduction by the radio program host, Lhévinne delivers one of the most fiery accounts of the work that I’ve heard.

There is regrettably no known surviving film footage of the pianist with audio – only this fascinating 1931 silent film of Lhévinne practicing at the Hollywood Bowl on August 21, 1931, prior to a concert … if only we had the sound that went with it!

It is remarkable to consider that the following account of Mozart’s Sonata in D Major for Two Pianos K.448 that Josef & Rosina was not approved for release, only being issued many years later. After their initial attempt of June 11, 1935 they returned to the studio on May 23, 1939 (which yielded no other recordings that I am aware of) to give the work another try: that too was not sanctioned for release. The eventually issued performance consists of takes from both sessions and there is nothing in this recording that strikes me as unworthy of publication – a wonderful performance by both pianists.

To close, a fascinating video by American pianist John Browning that provides insight into the teaching methodology of both Josef and Rosina, with a clear demonstration of how they produced the beautifully burnished sound for which their playing continues to be esteemed.