“My earliest reaction to music, as far as I can recall, was one of fascinated terror.” It seems amazing that a pianist who produced one of the loveliest sonorities ever captured on record would have this initial response to the art form to which he would dedicate his life, but so said Harold Bauer in the opening of his autobiography Harold Bauer: His Book. Fortunately for posterity he overcame that adverse reaction and became a performer and teacher of great distinction, as well as a recording artist who left behind a small but precious discography of remarkably beautiful performances.

Bauer was born near London on April 28, 1873 and would soon overcome any fear he had of music: on his fourth birthday he composed a polka and would soon after have piano lessons from his aunt and violin lessons with his father. It was the latter instrument that was his prime focus for many years, and he was not the only pianist to have started with this instrument: Dinu Lipatti, Clara Haskil, and Egon Petri all began with the violin before becoming pianists. The great Joseph Joachim took an interest in Bauer when the ten-year-old boy wrote him a letter asking him to play a certain Bach Prelude and Fugue as an encore “because I play that piece too.” Joachim wrote back with an interest in hearing him play, and when he did, he encouraged him to study at the Royal College of Music; however, Bauer’s father instead had him study with the great teacher Adolph Pollitzer, with whom Bauer would learn the entire violin repertoire.

On the advice of Paderewski, Bauer moved to Paris to get ahead in his career as a violin soloist. Once there, he worked as a piano accompanist to make some extra money, leading to an opportunity to tour Russia accompanying the singer Louise Nikita at the piano. He had already performed admirably in London, with programmes including Liszt’s Feux Follets and St. Francis Walking on the Waves, and when he became more visible accompanying other musicians at the piano, this instrument would become his focus. He stated that he had “become a pianist in spite of myself, yet I had no technique and I did not know how to acquire it,” but he was soon engaged by Paderewski’s London manager to play two concerts in Berlin, the first of which consisted of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto, Saint-Saëns’s G Minor Concerto, and Liszt’s Hungarian Fantasia – “a thoroughly conventional program, typical of those days,” he wrote of something that would be inconceivable for a pianist today, let alone for a musician for whom this was their second instrument. The performance was a great success and Bauer’s trajectory as a professional pianist was set.

While he made quite a career as a soloist, Bauer was still active as a chamber music player and he toured Brazil with Casals in 1903. The following year, they met with Ernest Schelling in Rio and it appears that critics had divided themselves into two camps, those who preferred Bauer and those who proclaimed Schelling the superior pianist. To take advantage of what they viewed to be ‘ridiculous but amusing,’ they created a huge musical event together with the local pianist Arthur Napoleao at the Opera House: “We engaged the entire Opera orchestra, and each of us played and conducted alternately, using every possible combination of duet and trio throughout the evening.” Reproduced here on the left, courtesy the Brazilian Piano Institute, is the programme of the remarkable event, which I’ve never seen published before. Artistically the concert was a success, though a scuffle broke out between a Bauerite and a Schellingite in which Schelling himself intervened – ironically, he was the one who got punched and a bloody nose. Despite this whole situation, Bauer and Schelling remained very good friends (years later they would both serve on the Artist Auxiliary Board at the Manhattan School of Music) and when they ended up on board the same ship taking them home shortly after this concert, they “astonished the passengers by the magnificent duets [we] played upon any and every musical instrument obtainable on board.”

As an interpreter, Bauer played without excess although he was not one who worshipped the text and the intention of the composer over individual performance. Although he would look attentively to the score – indeed, he edited a great many works for Schirmer – he believed it was important to bring one’s own intelligence to one’s reading of it. “The ordinary man who fails to realize what lies in the music beyond the printed indication is just…an ordinary man.” After relating a tale about how examining various editions and the manuscript of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata led him to adjust his approach, he stated that, “the composer, as a general rule, cannot be regarded as the most reliable guide to the interpretation of his music. The best proof of this is that in those rare cases where the composer is a fine executant and plays his music as well as it can be played, it is not difficult, if the performance is compared with the printed page, to find literally hundreds of details where the two fail to correspond.” Listening to his playing, however, we do not hear an excessive display of individuality but rather a respectful balance of personal style with the music being played.

Like many pianists of the time, Bauer produced player-piano rolls and he was in fact one of the most prolific pianists in this medium, making over 100 such rolls. Unfortunately he did not make as many records: he began recording in 1924, making only two discs with the acoustical recording process (whereby the instrument was amplified with a cone-shaped horn) before the new technology of electrical recording (with the use of microphones) was employed. He also made an early film appearance and we can see him in this April 2, 1927 footage accompanying violinist Efrem Zimbalist in the last movement of Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata. This piece meant a great deal to him: he wrote enthusiastically about Joachim’s performance and how the last movement needed to be repeated as an encore.

The existence of this footage may be more historic than we might imagine: Bauer writes in his autobiography, “I was engaged to take part in the first demonstration ever staged of moving pictures combined with sound. This was arranged by Warner Brothers at the theater on Broadway which bore their name. There were a number of performers on this … occasion of historic interest. I played part of the Kreutzer Sonata with Efrem Zimbalist.” In this amazing film we can see Bauer’s effortless technique and fluidity of movement. On the same occasion he apparently recorded Chopin’s Polonaise Op.53 but that footage has regrettably not been made available – one certainly hopes that it will!

Even before this filmed performance, Bauer’s first large-scale recording was of chamber music: on December 21 & 23, 1925, he made the first recording of the Brahms Piano Quintet Op.34 with the Flonzaley String Quartet, with whom his close friend Ossip Gabrilowitsch would record the Schumann Piano Quintet Op.44 two years later (they had recorded a truncated account of the latter work in 1924). Bauer’s integrity as a musician shines through in his collaborative approach, never overpowering the musicians he plays with in this spirited performance.

Harold Bauer’s 1935 recording of Schumann’s Fantasiestücke Op.12 is the first of the work (the second would be Arthur Rubinstein’s 1949 account). While Bauer had made his earlier recordings for Victor in the US, in this case he set down this reading at their sister company EMI’s Abbey Road Studios on their Steinway piano. The pianist was evidently in good form at the session, as 5 of the 8 sides required only a single take, the remaining 3 receiving no more than a second attempt. Throughout this account, we hear Bauer’s sumptuous singing sonority, fluidly phrased legato line, purity of tone at all dynamic levels, and balance of primary and secondary voices.

Very few broadcasts of the pianist have been located and none have been made commercially available, but fortunately some are on YouTube. This May 24, 1936 broadcast of Bauer playing Chopin’s Third Scherzo is also of great interest, as it is a work he never recorded commercially. His wonderfully clear sound, refined dynamic and tonal colours, and magical pedal effects are a marvel to behold.

Bauer is today better remembered for his readings of the German and Romantic repertoire, yet he also played the new music of the time, giving the Paris premiere of Debussy’s Children’s Corner suite and the New York premiere of Ravel’s Concerto in G Major. Those who are surprised by this might be even more amazed to know Ravel dedicated Ondine from his now-legendary suite Gaspard de la nuit to Bauer – alas, although Bauer played it the world over for decades, he never recorded it. In one of his two recorded performances of Debussy, the lesser-known Reverie, we hear his glorious singing tone and mastery of the pedal helping mould the colours and dynamic gradations called for by this music.

Bauer’s last recordings were made on January 8 and 9, 1942 of works by Grieg, another composer whom he knew after having met the Norwegian in Amsterdam at the home of their mutual friend Julius Röntgen. For some reason most of these performances were unissued, among them the three Lyric Pieces presented here (The Butterfly Op.43 No.1, Valse Impromptu Op.47 No.1, and Nocturne Op.54 No.4):

Bauer would retire soon after this session, spending his remaining years in Miami. He was tired of the performing and touring life and stated in his autobiography, “I am never going to practice the piano any more.” Yet he stayed active in musical arenas, as he had his whole life. Having emigrated to the US during World War 1 (he was naturalized in 1917), he was founder-director of the Beethoven Association of New York (1918-1941) and president of the Friends of Music of the Library of Congress. For years Bauer had headed the piano department at the Manhattan School of Music (he was founding member of their Artist Auxiliary Board in 1918 and gave his first master classes at MSM in 1924) and beginning in 1941, he taught master classes each winter at the University of Miami while serving as Visiting Professor at the University of Hartford Hartt School of Music from 1946 until his death in 1951 at the age of 77.

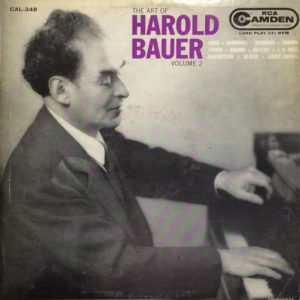

Despite his relatively small discography for an artist of his stature and a reputation that waned even during his lifetime, RCA produced two LPs that featured his 78rpm discs in the early years of the new medium, an honour also granted Rachmaninoff and Paderewski but not Levitzki or some other great pianists to have recorded exclusively in the 78 era. Years later, the International Piano Library (later Archives) produced an LP featuring some of his rarer recordings, including the Brahms Third Sonata recorded for the lesser-known Schirmer label (added below this paragraph). Today, his complete solo recordings are now available on a marvellous 3-CD set on the APR label (it does not include the Brahms Quintet). While we may wish for more recordings – and perhaps some more broadcast performances will turn up and be made available – we should be grateful that we do have what we do of this superb musician. Not only are his recordings required listening, his autobiography should be required reading for insight into the universal issues facing musicians and even society as a whole.

Since this feature was originally produced, a brief film snippet of Bauer at a double-keyboard piano showed up, as well as a radio broadcast in which he played the first movement of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto – the only extant recording of him playing with an orchestra. I have given those film and broadcast performances their own page on my site – click here to check those out.

If there is one recording for which Harold Bauer should be remembered, it is the Valse from Arensky’s Suite for Two Pianos Op.15, recorded with Ossip Gabrilowitsch at the other piano. The two pianists did at least 13 takes over the course of four sessions at Liederkranz Hall in New York between June 13, 1928 and September 19, 1929, with the issued take being the final one (matrix number CVE 45630-13). This is one of the most charming piano recordings ever made: Bauer and Gabrilowitsch play with a gorgeous full-bodied sonority, fluid legato phrasing, beautifully refined dynamic shadings, silky pedal effects, wonderfully defined articulation, and a delightful rhythmic lilt, all of which make this such an infectiously joyous performance, a testament to his inspired music-making and glorious pianism.

Comments: 2

Thank you so very much for this monumental homage to Harold Bauer…a great artist and musician!

According to one of my early teachers who had lessons with Bauer: “ He was greatly influenced by two younger pianists: Carl Friedberg and Benno Moisiewitsch.” This might account for his amazing control and color palette?

So glad that you enjoyed this feature. One could certainly do worse than have Friedberg (who was in fact a year older) and Moiseiwitsch as models of tone production! I think that his colour palette was probably aided by his having played the violin for so long – something to do with how his fingers connected with the keys… Lipatti, Haskil, Petri too!