The 100th anniversary of the birth on November 5, 1921 of György Cziffra provides an opportunity to consider the true nature of one of the most misunderstood of pianists. His capacity to play the most challenging works with phenomenal speed and dexterity has led to his being viewed as a ‘circus performer’ – no doubt in part due to his having actually played in a circus at at the age of 5 (more on that below). The natural-born musician and artist may not have been an academic, but he was certainly very intelligent and comprehensive in his musical approach. It could be the fact that he came from humble beginnings and made his way to the upper echelons of a cultural milieu that can be perceived as high class that has been at least partly responsible for the derision he has faced in some circles.

As he himself states in this video excerpt of a French interview, Cziffra hated the terms ‘virtuosity’ and ‘technique’ despite his own extraordinary capacity. I have posted a rough translation of the conversation and subtitles below the video.

Translation:

“I really don’t like the word ‘virtuoso.’ I know what it means, because I am a real virtuoso; I was born this way.”

Nicknamed ‘the pianist with 50 fingers’, György Cziffra impressed many with his technique and his interpretations of works by Liszt and Chopin.

Born in Budapest, he gave his first performances in a circus.

“I already worked like a little mouse, for hours and hours … and consequently was booked to play in a circus. I was five years old. Since that age, I’ve been a slave to music.”

“Did you have toys when you were a child?”

“Never. Never. I played with my piano, that’s all.”

“You worked too hard!”

“For eight years, almost non-stop. Eight hours, ten hours a day… every day, even Sunday.”

“You have must have left exhausted!”

“I don’t know…”

“It’s a battle with the piano.”

“Ah yes, it’s always like that. Eight hours, really, ten hours of work a day… after that, I’m dead. After that, how can I leave the house to go to Paris, to go to a great restaurant, all dressed up… I can’t.”

“One day Alfred Cortot spoke to me about you – he said ‘As a virtuoso, he has 300 years’ experience and yet he has the soul of a child.’”

“What does it mean, virtuosity? Again: it’s a question of work. Hours and hours … I really don’t like the word ‘virtuoso.’

Revered for his virtuosic technique, Cziffra nevertheless tried to distance himself from it. “I have a suppleness, and I was born with it – that’s all.”

The pianist simply wanted to return to musicality … In 1967, Cziffra declared, ‘The word ‘technique’ I find to be detestable.’

—

One need only hear Cziffra in a Scarlatti Sonata to recognize that he was an extraordinarily sensitive musician who was not only capable of the most refined nuancing who did so as the music required. Nowhere in this filmed July 22, 1962 BBC television broadcast of Scarlatti’s Sonata in A Major K.101 is there a harsh or abrasive sound, or a nuance that is either overlooked or overdone.

Unfortunately, the fact that a few major critics have over the years accused him of superficiality seems to have led to this narrative being believed by much of the public, despite abundant recorded evidence to the contrary. His virtuosic performances certainly are dazzling and exciting, not ‘brutal’ as some have suggested (that word was a popular one with some critics in France); they feature the same volcanic intensity for which other pianists are praised while also being more intelligently conceived than many other performers’ traversals.

This filmed interpretation of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No.6 from the same BBC broadcast as the Scarlatti above is a perfect example of his mastery of the composer’s idiom as well as his technical proficiency. Cziffra had a particular affinity for the works of his compatriot, bringing to his readings idiomatic inflection while also going above and beyond their technical demands and adding a few personal touches, as was commonly done in the composer’s lifetime. The lyrical sections are played with truly natural timing, reflecting the folkloric nature of the musical content, while the pianist’s virtuosity is simply jaw-dropping. Indeed, his dexterity needs to be seen as well as heard to be believed, some of his feats being almost impossible to fathom.

Prepare yourself for the rapid-fire octaves in the closing section and remember that you are witnessing a fully unedited performance; even as you see his hands moving with such speed with your own eyes (particularly in the last 90 seconds), you might not believe it!

One must keep in mind that what Cziffra is doing is what the music demands and requires: Liszt elevated what was possible at the piano with his masterful and innovative writing, and audiences were indeed thrilled by what they heard, as was the intent. In these showpieces – that are not devoid of musical content (Liszt, like Cziffra, was and still is often misunderstood) – Cziffra certainly delivers dazzling fingerwork. This filmed performance of the Grand Galop Chromatique is a fine example. While the Rhapsody above also has a good deal of lyrical content, which Cziffra played truly sensitively and idiomatically, in this particular work we have the pianist doing what the composer intended: stunning the audience with digital pyrotechnics. And yet he does so without a losing the pulse, melodic and harmonic clarity, or tonal quality.

Cziffra’s humble beginnings and suffering throughout his life surely impacted his communicative gifts. Born into a poor family, young György was somewhat weak and suffered from poor health in his early childhood. He got some coaching at playing piano at the age of four by his father, whom he described as a ‘cabaret artist’, after having been drawn to the instrument when seeing his sister Yolande practice (he would try to imitate her every move). By the age of five, he was practicing long days and would improvise for hours on end at a circus – his parents were told that their son was “a perfect circus artist, a second Offenbach.”

He moved into more illustrious settings when he was enrolled at the Franz Liszt Academy, albeit under unusual circumstances. The boy and his mother traveled to the Dohnányi’s home for an audition that they had been told had been arranged but in fact had not; they finally convinced the doorman to let them in and despite an aversion to child prodigies, Dohnányi heard the boy and proclaimed him to be not just “a rare pearl” but rather “the pearl of pearls.” He became the youngest pupil ever to join the Academy, where he studied with both Dohnányi and Imre Keéri-Szántó, who studied with Liszt’s pupil István Thomán (who also taught Dohnányi).

Miraculously, there is some film footage of the young boy playing some Schubert in 1934:

Cziffra studied at the Academy from 1930 until 1941, when he had to enter the army. His wife Soleykka was pregnant when he was sent to fight on the Russian front, where he was captured and held as a prisoner of war. He was able to resume piano once the war ended, playing in bars and clubs in Budapest and touring with a jazz band. The couple had unsuccessfully tried to escape the communist regime in 1950 and György was sentenced to hard labour until 1953. He suffered damage to the ligaments in his arms after being forced to carry 130-pound loads of concrete up six flights of stairs; it is for this reason that he wore leather support straps on his wrists, which are occasionally visible in some photos and film.

After this period he continued both classical and jazz performances, his ability to improvise serving him well in the latter. His compatriot Tamás Vásáry heard him play in the Kedves bar in Pest at this time, where “the cigarette smoke was so thick you could hang your coat on it.” Through the smoke, Vásáry heard the playing of four hands or two pianos and but could only see a single instrument and asked the bar owner where the second pianist was; he was told, “There is no second pianist. That’s Cziffra.” Vásáry began to attend the club regularly and stated, “I tried to watch and figure out what he was doing, because he was so fast, that I, another piano player, couldn’t even follow his movements – I had no clue what he was doing.” Vásáry noted in the same interview that Cziffra was more than a virtuoso, highlighting his incredible imagination, personality, and soul.

Cziffra made only a couple of hours of recordings in his native country, his first commercial sessions taking place between 1954 and 1956. However, before producing these discs, he cut one private 78rpm record in 1949 featuring Les Moissonneurs by Couperin (a mainstay of his repertoire) and Chopin’s Etude Op.10 No.4, which were included in a CD accompanying his biography published by the APR company (dated 1948 in that release but since confirmed to be 1949). Here are those two performances:

His first session for the Hungaroton label took place on October 21, 1954 and included this performance of Liszt’s Valse oubliée, played with charm and elegance, with beautifully defined articulation, marvellous pedal effects, gorgeous dynamic nuancing, and evocative timing.

A landmark concert took place on October 22, 1956 when Cziffra played Bartok’s Piano Concerto No.2 in Budapest with Mario Rossi conducting. The pianist claimed he had learned it in 6 weeks when the soloist originally booked for the concert decided that he was unable to learn the piece in time, but that has been disproven as he was booked in May for that October concert. Additionally, Cziffra performed it in several cities in Hungary around that time.

He wrote of the event in his memoirs: “The great day arrived and the concert was a triumph of some portent. The audience was a cross-section of a people weary of the excesses of a regime whose victorious army had, after eleven years, still not returned home. Despite its stupefying complexity, the music is perfectly structured, which enabled me to surpass myself so that it seemed like molten lava to the audience. Some two thousand people, normally so disciplined, rushed from the hall singing the National Anthem, ripping down, as they ran along the nearby streets and avenues, anything bearing emblems other than the national flag. There was an uprising and the government (responsible for an even worse police state than the one they had copied) fled to a new refuge. The frontier half opened. While people rushed into the breach in tens of thousands, the revolt was rapidly put down and a new regime did its best to gloss it over as a mere passing error. Time was running out: the breaches in the demarcation line were being closed. This time, I chose exile of my own accord. I was quite ready to assume my status as a free man and artist.”

As captivating as the testimonial is, if the audience had left the hall after the concerto in the first half and not attended the Brahms Symphony in the second half of the programme, contemporary newspaper reports surely would certainly have commented on the (nearly) empty hall, but they did not. One review of the concert states that

“His interpretation was a great achievement in itself; his playing made the complex work, which is not easy to understand, sound clear and captivating. But we must also take into account Cziffra’s individual development, from his debut recital some years ago to this production. Our artist has now almost reached full maturity. The differentiated world of Bartók’s music is open to him… and we feel that this opens the way to all the stylistic periods of music literature and to all its masters.”

A recording of Cziffra playing the work was issued using a tape from Cziffra’s widow’s collection, with Mario Rossi as conductor, and while the date on that release was that of the 1956 Budapest performance, the director of the Cziffra Collection, Erik Pagini, is convinced that the recording is in fact from a performance in Italy – also with Mario Rossi on the podium – given in 1959 (research is being done to locate the precise date). It was the pianist’s widow who had presented the tape to EMI, suggesting the date of the famous Budapest concert without verifying the details of the tape source (which is indeed an authentic Cziffra recording). The belief that this would have been the Budapest concert could easily be fuelled by the oft-quoted tale that Cziffra would not perform the concerto again until Hungary was free, but there is evidence to indicate that this was not accurate: Cziffra in August 1957 wrote to Lajos Hernádi (born Lajos Heimlich, a pupil of Bartók and Schnabel, and a prize winner of the Liszt competition in 1933) that he planned to record the Bartók Concerto in London in September 1957, something that regrettably did not transpire but which reveals that he did not refuse to play the work again. (Many thanks to Ferenc János Szabó for uncovering this important piece of information and for the newspaper clipping reproduced here.)

Regardless of when the performance on this recording took place, it is indeed one filled with excitement and tension, Cziffra’s stunning blend of virtuosity and musicality on full display in this extraordinarily challenging work. His fiery passion and rhythmic vitality highlight the intensity of the work, yet he plays with transparent textures and burnished tone without tipping over into aggression and harshness.

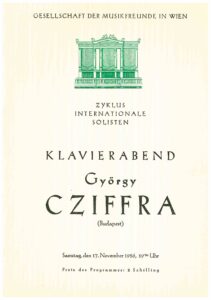

Cziffra made another attempt to escape Hungary during the 1956 Revolution, and this time he was successful. He arrived in Vienna and very soon after, on November 17, had the opportunity to give a recital when his compatriots the Tatrai Quartet were unable to perform as scheduled. The recital was an astounding success (if only a recording could be found!), reviewers noting the temptation to brand him as a Liszt specialist and that doing so would diminish his other talents, as evidenced in his performances of Mozart’s A Minor Sonata and Beethoven’s 32 Variations.

His Paris premieres were also a resounding success: he made a television appearance as early as December 4, and several concerto and recital bookings followed. Fortunately at least one of these was recorded: a blazing April 10, 1957 performance of the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No.1 with Carlo Maria Guilini conducting. They took the work at quite a pace (giving the legendary Horowitz/Toscanini accounts a run for their money), although the last movement is likely a bit slower than Cziffra wanted, and this scorching traversal is astounding in all respects. As thrilling and exciting as the performance is, Cziffra’s attentive musicality is on full display as well, with a clear singing line, crisp and consistent articulation, polished tone, and burnished phrasing. This recording is receiving its first official release in the new centenary edition released by Erato.

He was a great hit in London soon after, and did a series of appearances at the Hollywood Bowl in the summer of 1957 that were, according to the press, quite stupendous, but unfortunately no recordings of those performances have been found. A year later he gave a series of concerts in New York, playing Liszt’s First Concerto and Hungarian Fantasy (the same programme as in London) four nights in a row with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Thomas Schippers.

Once again, we are fortunate to have a recording from this series, the third performance from November 1. Cziffra’s spacious and elegant approach to the opening movement of the First Concerto in this performance is a fine example of his exquisite sensitivity: he could easily have taken it faster but chose to emphasize the work’s lyrical nature. What a polished sonority, gorgeous lyrical phrasing with poised voicing, natural timing, refined dynamic and tonal nuances, and thrilling rhythmic momentum!

Cziffra felt at home in France – his parents had in fact lived in Paris before World War 1 – and he would in 1968 take French citizenship, changing his name to Georges. He made a great many appearances on radio and television over the course of his several decades there, soon becoming a favourite in his adopted country, despite some critics not being totally enamoured by his artistry.

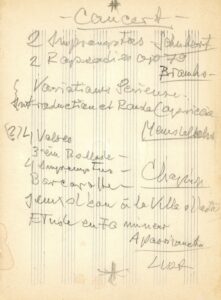

He gave considerable thought to programming his recitals to create a flow of narrative and range of styles, even when featuring works by only one or two composers; as can be seen in this unpublished sketch from his notebooks (which contain an abundance of such programmes) and also the recording below, he crafted beautifully considered and structured programmes.

This relatively early recital is a fine example of his early playing: an unreleased June 19, 1960 Strasbourg recital that finds the pianist playing a broad variety of repertoire. This recording captures Cziffra’s tonal colours marvellously well, and we hear him in a range of works that demonstrate his interpretative gifts. What sumptuous CPE Bach, Scarlatti, Lully, and Hummel – repertoire with which he is not generally associated but plays exquisitely – as well as fascinating Beethoven and Schumann before he launches into performances of both lyrical and virtuosic Liszt works.

Some of the most famous archival footage of Cziffra comes from BBC television appearances in 1962 and ’63, from which the Scarlatti and Liszt Rhapsody links above derive. Among the most famous of these clips is a warm-up not intended for broadcast but which has circulated and become the stuff of legend: Cziffra weaves in and out of some known works (including Chopin’s Op.10 No.1) while extrapolating and improvising in an astonishing manner. His playing here is vivacious, bold, impetuous, and dynamic – and it may be that his personal treatment of some standard repertoire in this off-the-cuff not-for-broadcast reading led some to believe he was not a serious musician. However, as the actual performances from the broadcast reveal, he most certainly was a dedicated interpreter.

Cziffra traveled internationally to great acclaim, and the link below to an absolutely stupendous recital given in Tokyo on April 23, 1964 showcases the full range of Cziffra’s tremendous music-making gifts. His Chopin readings here demonstrate sumptuous tone, gorgeous legato phrasing, sensitive nuancing, and masterful balance of voicing and timing that are put to great musical use. The spacious and grand framework of the opening Fantasie, for example, is noble and dignified, remarkably restrained and sensitive without ever degrading into sentimentality.

There’s no doubt that when it came to the showpieces – particularly the final two Liszt works on the program – what he did technically was nothing short of jaw-dropping: he achieves such super-human speed with octaves, repeated notes, and runs that one might expect that the performances were somehow doctored. However, film footage of the Grand Galop Chromatique from this very concert has survived (sadly it is the only work whose film is extant – I will post it below this audio recording of the recital) and like the filmed performance of the Sixth Hungarian Rhapsody higher up on this page, as well as the other performance of this same work, this video seems to show his hands moving faster than is humanly possible.

There’s no doubt that when it came to the showpieces – particularly the final two Liszt works on the program – what he did technically was nothing short of jaw-dropping: he achieves such super-human speed with octaves, repeated notes, and runs that one might expect that the performances were somehow doctored. However, film footage of the Grand Galop Chromatique from this very concert has survived (sadly it is the only work whose film is extant – I will post it below this audio recording of the recital) and like the filmed performance of the Sixth Hungarian Rhapsody higher up on this page, as well as the other performance of this same work, this video seems to show his hands moving faster than is humanly possible.

Not only is his speed extraordinary, but how he captures the spirit of the music, playing with biting humour with his idiomatic timing – exaggerated in other hands perhaps, but perfectly natural in his. Absolutely stunning, earth-shattering, sky-opening playing!

The YouTube upload of the full recital does not permit embedding it on other sites so click here to play the recording.

And here is the stunning video performance of the Grand galop chromatique from that recital – let us hope that a film of the complete recital is found!

Here is some terrific film footage of the pianist in a November 20, 1965 concert performance of the Variations symphoniques by Franck with the pianist’s son conducting the Orchestre National de l’ORTF. Cziffra plays (on a Pleyel piano) with supple phrasing, attentive voicing (the punctuating bass notes in lyrical passages are beautifully resonant), emotive rubato, and a remarkable dynamic range (what a pianissimo!).

In 1973, Cziffra bought the dilapidated Royal Chapel of Saint-Frambourg in the French town of Senlis and with his own earnings paid for and oversaw its restoration over the course of two decades. His friend Joan Miró donated eight stain-glassed windows to the structure (five in the choir, three in the facade) and Cziffra played and recorded many concerts there.

Sadly, his final years were marked by more hardship. Cziffra’s son – a conductor with whom he often performed (as seen in the Franck video above) – died in a fire in 1981, a tragedy from which the pianist never recovered and which led to him never playing with an orchestra again. He continued playing and teaching until his death in 1994 of systemic cancer.

Cziffra devoted more time to teaching late in his final years, giving master classes at Senlis that are a testament to his musical intelligence and communicative powers. This private tape of some masterclasses held in this venue are a fascinating insight into his artistry.

As this final musical example (below) in this tribute reveals, Cziffra still played with extraordinary musicality and sensitivity late into his career. This album of French Baroque keyboard music recorded in Senlis between 1980 and 1986 runs completely counter to the pianist’s reputation as the arch-virtuoso, being relatively ‘simple’ as far as digital dexterity is required, but yet again Cziffra delivers musically – in spades. In these works by Daquin, Rameau, Couperin, and Lully, we hear gorgeous tonal colours throughout, whether with fluid or crisply defined articulation (which he always does with consistency and intelligence), while his use of pedal always judicious, his rhythm regular without being rigid, and his tonal and dynamic nuancing always sensitive and refined.

There may always be those who will never consider Cziffra to be the refined artist he was. He never quite fit in anywhere in his life, from his childhood through his studies at the Academy to the war years and his time as an exile, and the same is true of his position in the pantheon of classical pianists. But there is no doubt that he holds a position alongside the greats, a unique artist of astounding natural capabilities who overcame tremendous adversity and worked diligently (and heartfully, if such a word could be coined) to bring his all into his music. What a legacy he has left us.

Many thanks to Erik Pigani, Christian Lorandin, Ferenc János Szabó, Máté Cselényi, and Rinaldo Zerafa for their assistance in gathering information and material for this tribute.