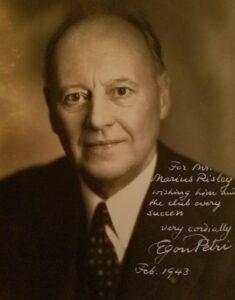

The German-born Dutch pianist Egon Petri has been a favourite of mine from my earliest years of collecting records. The APR label had put out the bulk of his 78rpm recordings on three double-CD sets and I was particularly mesmerized by his Liszt and Schubert-Liszt performances; my high school physics teacher, from whom I had learned a ton about historical piano recordings (but precious little about physics), had waxed rhapsodic about Petri’s Mazeppa and Ricordanza.

The German-born Dutch pianist Egon Petri has been a favourite of mine from my earliest years of collecting records. The APR label had put out the bulk of his 78rpm recordings on three double-CD sets and I was particularly mesmerized by his Liszt and Schubert-Liszt performances; my high school physics teacher, from whom I had learned a ton about historical piano recordings (but precious little about physics), had waxed rhapsodic about Petri’s Mazeppa and Ricordanza.

However, it was experiencing some of his 78s on an old turntable with built-in tube-amplified speakers that made me realize the power of his playing. A pianophile friend was visiting from Europe and we put on one of the Petri 78s I had on this system and it felt like Petri was in the room; the beauty and grandeur of his tone were more apparent to us than ever, despite the fact that we were both familiar with the recordings we listened to.

The more I explored Petri’s discography, the more I became aware that some of his studio discs were far more inspired than others and that his concert recordings seemed to capture his playing at its impassioned best. That said, he could still deliver stunning performances in the studio. This page will feature, in celebration of the pianist’s 140th birthday, a selection of his finest commercial and concert recordings.

Here are his first commercial discs, made at a studio session for German Electrola on September 17, 1929, and featuring some dazzling pianism. As I wrote about these performances in the booklet notes for the APR reissue of Petri’s entire 78 discography and first LPs (a commission for which I was truly honoured and grateful), ‘throughout, one marvels at his even articulation, sparkling tone, subtle pedalling, and gloriously shaped phrasing.’

The 78rpm disc that I consider his most successful is his glorious September 27, 1938 recording of Liszt’s transcription of Schubert’s lied ‘Gretchen am Spinnrade.’ What exquisitely-shaped phrasing, a beautifully sculpted line, wonderful layering, impassioned climaxes, and gorgeous nuancing – the long arc of his trajectory in this performance is magnificently achieved.

A few days before setting down that account, the pianist made on September 22, 1938 a recording of Liszt’s Piano Concerto No.2 in A Major, with Leslie Heward conducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra. This is a reference recording for this work and also one of Petri’s more successful studio efforts, with a wonderful balance of passion and sensitivity on display thanks to his beautiful sonority (his tone in lyrical sections is exquisite), broad dynamic range, refined phrasing, and impressive technical capacity (his octaves are terrific!).

As great as that studio recording is, the live account below shows how much more intensity he could bring to his playing in concert and makes for a fascinating comparison. I was less familiar with this live 1945 performance that circulated on a bootleg LP that eluded me for a long time, and now that it’s online, I can say that this version could well supplant Petri’s superb studio account in my estimation.

This performance has all the elegance, refinement, and dazzling technical mastery of his wonderful commercial recording with the bonus of more unbridled passion and propulsion. Aged 64 at the time of this reading, Petri sculpts his lines with burnished tone, mindful use of dynamics, and impeccable timing so as to highlight the emotional content of Liszt’s score – even though he lingers in lyrical passages, the faster sections are taken at quite a clip, resulting in a reading that’s a two minutes shorter than his commercial account and more animated and dramatic too.

Some magical broadcasts from 1930s reveal even more passion and vitality. Here is Petri playing the fourth movement of the Busoni Piano Concerto from a 1932 concert, with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by the great Hans Rosbaud. Petri was a disciple of the great Busoni – one of the pianist-composer’s three favourites – and so this recording is of particularly great historical importance.

Allan Evans, who discovered this performance and released it on his Arbiter label, recounted that he went to Melodiya’s offices in 1987: “Waited for a meeting room to be prepared (someone hurried inside with a reel of tape – not so subtle.) Met their archivist who claimed the entire 1936 broadcast [of the same concerto] existed minus the 1st movement, in a private collection. The Red Army took everything in 1945. Two years later during Perestroika the 1932 Busoni movement and most of Totentanz emerged. The 1936 performance seems to be missing unless an army officer will ‘fess up. Took a while to get them. Worth the effort.”

Worth the effort indeed. It is staggering that a 1932 broadcast should exist at all and in such amazing sound, and one shudders to think of the whole performance played this way by this great student of the composer; the 1936 Totentanz (with the opening missing) referred to above was also released by Allan on one of his Arbiter CDs and features equally stunning pianism (as shall be heard below the Busoni clip). This is absolutely thrilling playing, with the easily surmounting the technical challenges of this work despite playing at breakneck speed – what octaves, with incredible voicing and rhythmic vitality. A truly remarkable document!

And here is that other supremely important discovery by Evans, a stellar 1936 reading by Petri of Liszt’s Totentanz, again with the great Rosbaud on the podium. The first 78 transcription disc was not in the archive when Allan Evans rescued the rest of this performance from oblivion, but what a performance it is: thrilling passagework, massive tone, and rhythmically and emotionally charged playing.

One of Petri’s granddaughters told me that in the late 1950s, the pianist had gone to Switzerland in the hopes of teaching as his career was not going at its best, but that enrolment for his masterclasses was disappointingly far less than had been expected: it is sad and staggering to consider that only three students enrolled (one of whom was John Ogden). This recital given before those classes shows no sign that the pianist was in his late 70s at the time: his tone is rich and lush, articulation clear and precise, phrasing beautifully shaped, and timing natural and spacious.

Below is another marvellous concert performance of Petri late in life, a glorious account Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.4 in G Major Op.58. This recording was originally issued on a private LP Encore PHS-1277 which gave no date nor indication of the orchestra or conductor – a kind commenter on my YouTube upload has stated that it is the Carmel Symphony Orchestra, with an unidentified conductor, from a December 8, 1959 concert.

Petri put a few concerted works on disc in the 1930s and 40s, and several Beethoven Sonatas in both the 78rpm and LP eras, but he never recorded any of his concertos. A performance of the Emperor Concerto circulated much more widely than the interpretation of the Fourth below, which is a fascinating and insightful performance worthy of attention despite the unfortunately harsh sound of the amateur recording of this concert reading. His left hand voicing in the first movement cadenza, for example, is wonderfully highlighted with a level of robust dramatic inflection, in addition to a few personal touches that highlight the emotional depth of the work. Throughout the entire performance, we hear Petri’s bold emphases tempered by fluid legato phrasing, refined nuancing (what a wonderful pianissimo), and attentive voicing (notice the balance of his chords).

If Petri wasn’t always at his peak in the studio, it does not mean that his studio performances are not worth hearing. This 1956 account of Beethoven’s titanic Hammerklavier Sonata Op.106 for Westminster (for which label he produced several LPs) is a grand and noble reading, capturing with great fidelity the pianist’s gorgeous tonal palette (including a massive bass sonority), transparent voicing, and refined nuancing.

One of the greatest recordings we have of Petri is one that could very well have disappeared into thin air: a 1950s practice session of Alkan’s treacherous Symphony for Solo Piano Op.39 that was captured on tape in a Mills College practice room by his pupil Daniell Revenaugh, who told me about the experience when I met him about a decade ago. Revenaugh had to pull the microphone away from the piano partway through the first movement because the levels were peaking due to Petri’s volcanic playing.

This is indeed some utterly stupendous pianism here, the kind that gives us a much better idea of Petri’s true capabilities. The playing throughout features soaring phrasing, grandly shaped lines, clearly balanced voicing, wonderfully weighted chords, and rhythmic dynamism. The dramatic content and progression of the first movement is absolutely mesmerizing, and I’ve often listened over and over to that single section of the work in absolute awe. And this was simply a practice session – and at a time when Alkan’s music was not being widely played at all (this is before Raymond Lewenthal helped revive interest in the composer’s works). Stunning pianism by a grand master!

To close, Petri playing two of his own Bach transcriptions in a 1958 recording that showcases his beautiful full-bodied tone, fluid phrasing, and transparent voicing – a master musician at work, one whom we are fortunate to be able to appreciate in so many hours of superb recordings.