With 2023 marking the 120th anniversary of the birth of Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau on February 2, 1903, it is a fine occasion to explore the artistry of this legendary pianist. With a performing career that spanned eight decades of his 88-year life, Arrau left behind a massive discography over the course of six decades which began in the acoustical (pre-microphone) era and progressed through to the age of digital recording. His tremendous output bears witness to the evolution of one of the most philosophical pianists to have recorded.

One cannot underestimate the impact that Arrau’s training with Liszt’s pupil Martin Krause had on his artistic approach. With sponsorship provided by the Chilean government, Arrau began his studies with Krause in Berlin at the age of 10, accompanied to his first encounter with the master by his compatriot and fellow pupil Rosita Renard. Krause would become a paternal influence to the young boy (who had lost his father when he was but one year old), educating him in matters beyond his keyboard studies – art, philosophy, opera – without ever accepting payment.

Krause nurtured the young Arrau’s approach to playing with a Weltanschauung or “world view”, and his death in 1918 left the fifteen-year-old feeling abandoned and lost, not yet believing himself secure enough in his perceptions of music and interpretation. Thus began the pianist’s lifelong quest to create the most meaningful interpretation for each work he played. Having also been greatly influenced by hearing titanic pianists like Busoni and Carreño, Arrau developed a focus on big-scale, spiritually expansive performances infused with philosophical insight, an emphasis deepened by his experience working with a Jungian psychoanalyst in the mid-1920s.

As Arrau got on in years, his performances in general went broader in tempo and developed what might be described as a ‘weight’ that could at times become more lugubrious, particularly in his studio recordings. In a 1972 interview, Arrau said, “It worries me not having an audience, but I like recording none the less. You have to pull yourself together to present something that may be valid for a long time,” and it could be that his later discs carry the weight of his intent to preserve his playing – and yet without an audience, his preserved artistry was not quite what was heard on stage. Nevertheless, exploring his discography as a whole there is much to admire in a wide array of repertoire.

Arrau’s 1928 account of Liszt’s “Jeux d’eau a la Villa d’Este” is one of the crowning glories of his discography, notable not only for his glistening tone but for the spaciously timed transitions, which are seamlessly fused and elegantly phrased, and the stunningly beautiful trills. Arrau had learned from Krause Liszt’s own way with his works and that trills “were to be played…as a means of expression”, and in this reading they are certainly not empty ornaments but rather melodic and textural devices that add depth and colour.

A few years ago, a previously lost 1935 film in which Arrau played Liszt – as an actor as well as at the piano – was rediscovered and briefly circulated online (I reported on it here). While the audio needs some restoration, we can nevertheless hear the incredible intensity and passion that Arrau brought to his playing, far more so than even in his earliest and most celebrated solo discs. The one with the best sound is the opening Un Sospiro – what drama, fire, and sensitivity!

Not long after this film was produced we can hear Arrau in a stunning concert performance of Liszt’s Piano Concerto No.1 in E-Flat Major with Hans Rosbaud conducting. This 1942 traversal finds the pianist playing with the wonderful fusion of passion, sensitivity, and reflection that characterizes his earlier performances.

Just a year later we can hear the pianist in concert playing Liszt’s other concerto, the Piano Concerto No.2 in A Major, with Dmitri Mitropoulos conducting the New York Philharmonic. As in the 1st Concerto the previous year, Arrau eschews empty displays to fuse his virtuosity with the lyrical and emotional content of the work.

A year prior to the previous live performance, Arrau made what would have been a groundbreaking recording had it been released at the time: Bach’s Goldberg Variations, with all the repeats. As Arrau’s longtime friend and manager wrote, “One of the first major works Claudio Arrau recorded for RCA following the Carnegie Hall triumph in February 1941 that brought him his great American acclaim was the Bach Goldberg Variations. It was a natural choice. Arrau had won fame as a Bach exponent . . . and RCA needed the Variations in the catalog. But as fate would have it, it was never released. World War II was raging when Wanda Landowska arrived in New York as a refugee. To reestablish the reputation she had gained in America in 1924 and for much-needed funds, she gave a New York concert devoted to the Goldberg Variations. She then wanted to [re-]record the work. RCA asked Arrau if he would postpone his Goldbergs in favour of Landowska’s on the harpsichord. He readily consented, not only because he admired Landowska’s Bach enormously but also because at the time he was beginning to think that Bach’s keyboard works really belonged to the harpsichord. A few years later Arrau signed a long-term contract at CBS; RCA, having the Landowska success on its hands, saw no reason for the release of his recording, so it lay in the archives until now” – which was 1988, nearly half a century after the recording was made in January and March 1942. A spacious and contemplative performance that makes for compelling listening.

In 1947 Arrau set down the first of three studio accounts of the Brahms D Minor Concerto. Years later upon hearing the recording, the pianist himself could barely recognize his own playing: “When I hear it now, so fast and so straightforward – I just can’t understand it. It loses all meaning. Where one expects some lingering, it is so metronomic.” Having grown more consistently spacious with his tempi over the years (each reading was slower than the last), Arrau naturally might have felt less aligned with his earlier accounts, but that is not to say that this version is not marvellously played – as it truly is.

We encounter another facet of Arrau’s artistry in a 1951 recording of Debussy’s Prelude ‘La puerto del vino’, overflowing with magnificent colours, sinewy blending of tones and flexible timing, with exotic voicing and harmonization.

The same session produced a glorious account of Granados’s Quejas, o la maja y el ruisenor that soars with singing tone, expansive phrasing, and magical trills.

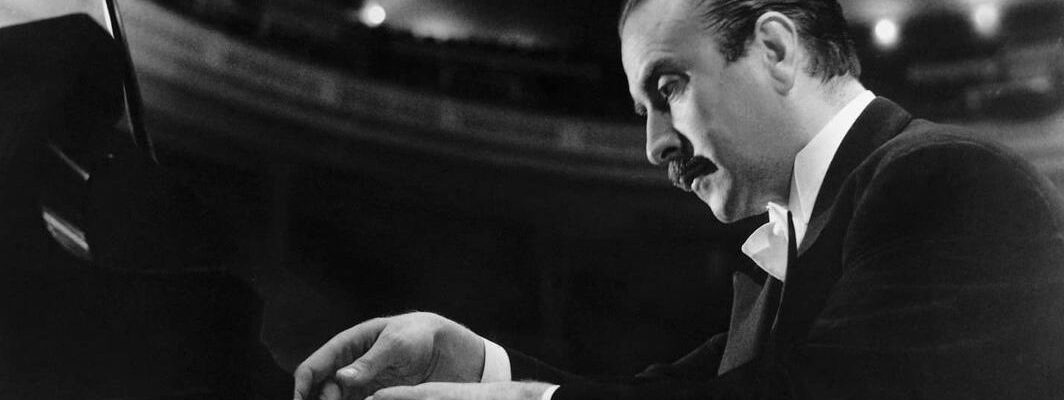

Here is some truly remarkable footage of Arrau playing three works in 1953, filmed at Carnegie Hall:

01:00 Mendelssohn Rondo Capriccioso

08:13 Chopin-Liszt “My Joys”

12:19 Liszt Gnomenreigen

The Chilean pianist is in terrific form here, playing with great passion and sensitivity. There is plenty of fire here, with expansive phrasing, wonderful rhythmic momentum, and tremendously clean finger work. The quality of this film is remarkable and the angles are absolutely amazing, with close-ups of the pianist, his hands, and the inside of the piano (a Baldwin!) all artistically accomplished.

As someone has colourized this footage, I thought it worth including as well for those who prefer to see it this way:

Rachmaninoff is not a composer one would associate with Arrau – he released no recordings of works by the composer and I don’t recall ever seeing any of his compositions on his concert programs – so it is probably quite a surprise that the Chilean pianist was chosen to play about 10 minutes of Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Piano Concerto for the 1954 movie Rhapsody, which can be seen by clicking here. Below are the audio excerpts that exist of portions of each of the three movements of the famous work, which find Arrau playing very idiomatically, with impassioned climaxes, lush phrasing, and emotive timing. Quite a departure from his standard repertoire – one that makes one regret that he chose not to play more of the composer’s music.

Arrau was one of many pianists who could communicate with more passion on stage than in the studio, and this fantastic filmed 1957 Sydney concert account of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra conducted by Nikolai Malko finds him performing with tremendous grandeur and nobility (this June 20, 1957 concert was the first live ABC TV orchestral broadcast).Arrau’s somewhat spacious tempi never devolve into the lugubrious pacing, his volcanic climaxes and masterful phrasing marvellously fused with his timing. A truly expansive and impressive reading – and it’s wonderful to be able to watch as well as listen to this brilliant and historic performance.

Another concert performance that’s been popular amongst collectors has been this 1960 Prague Spring Festival account of the Chopin Preludes Op.28. This bold and tempestuous traversal of the cycle is both expansive and contemplative, powerful and sensitive, is noticeably different in temperament from the bulk of what we hear in Arrau’s studio output – how fortunate we are to be able to hear over a half century later performance like this that give greater insight into the pianist’s true capabilities.

While Arrau’s later performances could be rather weightier, this was more often the case in his studio recordings, and concert appearances he could still play with more fire and vivaciousness than is generally heard in his sanctioned discs from the same period. This June 1978 concert performance of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto in Liverpool’s Philharmonic Hall with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Walter Weller is a case in point (and one offering a fascinating comparison with the Sydney performance from 21 years earlier): in his 75th year, Arrau plays with tremendous vivaciousness and fire in a reading with great nobility and authority. This is as ideal an example of his artistry with which to end this tribute as I can imagine.

Comments: 3

What a wonderful feast you have spread for us here, Mark. Bravo, and thank you so much!

Thank you for this wonderful compilation of performances by the hugely imaginative pianist Claudio Arrau.

His architectural sense was unfailing. He taught me to appreciate the silences and contemplative passages.

What a great, sonorous and resounding biography of Claudio Arrau! A full picture in sound. Of course the sound quality of old recordings take away one of his most commendable feature that’s his tone. But it’s a wonderful tribute. Thanks