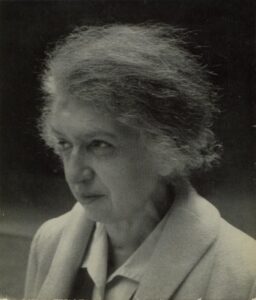

Clara Haskil died on December 7, 1960 as a result of injuries sustained in a fall at Brussels train station. She was only 65 at the time. The Romanian pianist had languished in obscurity for most of her life, finally enjoying international recognition in the last decade of her life, before this premature and truly tragic end.

It is likely Haskil’s suffering from several health issues and other challenges that imbued her playing with a sense of pathos that made her readings of the works of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schumann especially poignant; in Mozart and Schumann she was truly masterful in balancing the contradictory states of childlike innocence and existential angst. That said, Haskil was a brilliant interpreter of a much broader spectrum of the musical literature than is indicated by her official discography, which stems largely from studio sessions with the Philips and Deutsche Grammophon labels in the last ten years of her life. While a number of concert recordings have been released and therefore expanded her repertoire of recorded works, there are less-known private and test recordings that are equally revealing and valuable, offering glimmers of greater insight into this tremendous musician’s artistry.

It is likely Haskil’s suffering from several health issues and other challenges that imbued her playing with a sense of pathos that made her readings of the works of Mozart, Beethoven, and Schumann especially poignant; in Mozart and Schumann she was truly masterful in balancing the contradictory states of childlike innocence and existential angst. That said, Haskil was a brilliant interpreter of a much broader spectrum of the musical literature than is indicated by her official discography, which stems largely from studio sessions with the Philips and Deutsche Grammophon labels in the last ten years of her life. While a number of concert recordings have been released and therefore expanded her repertoire of recorded works, there are less-known private and test recordings that are equally revealing and valuable, offering glimmers of greater insight into this tremendous musician’s artistry.

The earliest recording we have of the artist is this Columbia test recording ca.1926 of Liszt’s Gnomenreigen – of interest not only because of its capturing Haskil’s playing almost a decade before her first issued recording of 1934 but because she would later produce not a single studio recording of Liszt’s music (although a later private reading of La Leggierezza exists). As can be heard here, her technique and musicality are put to perfect use in this virtuosic repertoire.

Although she made a few shorter recordings in the 1930s, it wasn’t until 1947 that she would make her first large-scale recording: an account of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.4 in G Major, conducted by Carlo Zecchi, who was a magnificent pianist himself (he was a disciple of Busoni) before becoming a conductor. Haskil plays with supple phrasing, remarkably transparent voicing, and glistening singing tone – the second movement is particularly ravishing, her voicing of chords being breathtaking.

Around the same time as this recording, Haskil gave a fascinating broadcast performance on the BBC, with Sir Thomas Beecham conducting, of Émile-Robert Blanchet’s Konzertstück Op.14. Haskil plays with a beautifully polished sonority, impressive virtuosity, and evocative nuancing (what wonderful pedalling). A fascinating and little-known rarity – a gem in her already glorious discography.

One of Haskil’s rarer studio recordings is a reading of the Brahms Piano Quintet Op.34 with the Winterthur Quartet (with Peter Rybar on violin), which was recorded around the late 1940s. Although she would record in a collaborative role with violinist Arthur Grumiaux, she did not record in larger ensembles except for this rarely-available performance (she also recorded no other Brahms in her studio sessions). The performance here features wonderful ensemble, beautiful voicing, rhythmic vitality, long lines, and that marvellous singing sound of Haskil’s (discernible through the clicks and pops of the LP transfer).

One of Haskil’s first LPs (perhaps the first) was a Westminster disc featuring 11 Scarlatti Sonatas (now available in this box set on Eloquence for which I wrote the notes), a marvellous example of her artistry, especially her noted capacity to play with astounding directness and clarity – the fluidity of her phrasing and beauty of her tone are beguiling. Anyone who thinks this music is ‘simple’ would do well to listen carefully to these performances and try to emulate a single phrase with such elegance, transparency, and refinement. The clip below features the 11 Sonatas on that rarely-reissued disc, plus 3 that she re-recorded for Philips the following year:

The Romanian pianist had a particular affinity for the music of Schumann, somehow always managing to bring out both the innocence and the darker undertones in his writing, all while playing in a disarmingly direct manner (the sample allies to her Mozart). Her gorgeous 1955 reading of his Kinderszenen Op.15 is a fine example: she plays with stunningly beautiful lyrical phrasing, discreet but attentive highlighting of inner voices, and wonderfully nuanced dynamic shadings. Utterly intoxicating pianism!

This 1954 recording of Haskil playing Mozart’s Sonata in C Major K.330 is a perfect example of how she was able to simultaneously reveal the simplicity and profundity of the composer’s musical idiom. With stunning clarity and variety of articulation, transparent textures, and an utterly gorgeous singing sonority, Haskil makes it all sound so easy (and it’s really not) – what incredible lightness, buoyancy, and beauty she brings to her performance!

Haskil’s crystalline playing was ideal for so many composers’ works. It is a shame that we have only one recording of her in Mendelssohn, a 1936 account of the Pièce Caractéristique Op.7 No.4, played with wonderful rhythm, clarity of articulation, and marvellous pedalling.

Even the many recordings of recitals that Haskil gave in the 1950s – circulated amongst collectors and unofficially released on LP and CD – are missing works by certain composers that she played, leading many to believe she never played them at all. This private recording of Rachmaninoff’s Etude-Tableau in C Major Op.33 No.2 is truly unexpected, as there’s not a note of Haskil playing Russian repertoire in her studio or concert discography. Despite having been captured on an amateur device on a somewhat out-of-tune piano, this performance is a fascinating opportunity to hear the Romanian pianist in this repertoire – the only known example of her playing a work by the great Russian composer. What long soaring melodic lines, spacious timing, and rich textures we hear in this fascinating performance!

As mentioned in reference to the Brahms Quintet recording, Haskil made no official recordings of solo works by that composer, which makes this home recording of the Capriccio Op.76 No.5 (one of two Brahms works she recorded at the time) all the more intriguing. Her clarity of texture and emotive timing reveal the harmonic richness of the music without the weightiness that seems to have become the norm today (über-serious readings of his works are now virtually ubiquitous), and her wonderful shaping of lines and gorgeous tone are appreciable despite the less-than-ideal piano.

To close this tribute to this unique artist, a fascinating work – underplayed in our time – that Haskil never officially recorded but of which we have two broadcast recordings: Hindemith’s The Four Temperaments. Here is her September 27, 1957 concert performance with the composer conducting the French National Orchestra. As always with Haskil, we hear transparent voicing, seamless phrasing, vibrant rhythm, and of course, gorgeous tone (notice the glisten in her trills). What a magical artist she was – inimitable and fortunately never to be forgotten.