Far too many great pianists did not have the international careers warranted by their talent or died tragically young – and sadly, several fit both of these sad circumstances. One such artist was Australian-born pianist Bruce Hungerford, a remarkable pianist who always seemed on the cusp of a breakthrough yet tragically died as the result of a car accident when he was only 54 years old.

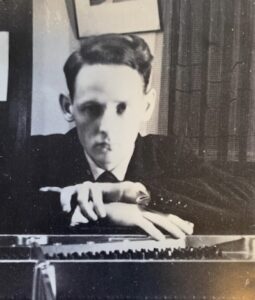

He was born Leonard Sinclair Hungerford on November 24, 1922 in Korumburra in Victoria, Australia, though from 1958 onwards he would be known as Bruce Hungerford. He later recounted that “when it came to naming me my parents were torn between ‘Bruce’ and ‘Leonard.’ I think they really wanted Bruce, but I was such a puny specimen that they hardly felt I fitted the name of the Warrior King of Scotland. Then a day or two before I was to be christened, my grandfather journeyed down to see me. He was a Scotsman to the backbone and after taking one look at me said sadly, “This is no ‘Bruce’, and so the die was cast, at any rate for my first 35 years.”

He was born Leonard Sinclair Hungerford on November 24, 1922 in Korumburra in Victoria, Australia, though from 1958 onwards he would be known as Bruce Hungerford. He later recounted that “when it came to naming me my parents were torn between ‘Bruce’ and ‘Leonard.’ I think they really wanted Bruce, but I was such a puny specimen that they hardly felt I fitted the name of the Warrior King of Scotland. Then a day or two before I was to be christened, my grandfather journeyed down to see me. He was a Scotsman to the backbone and after taking one look at me said sadly, “This is no ‘Bruce’, and so the die was cast, at any rate for my first 35 years.”

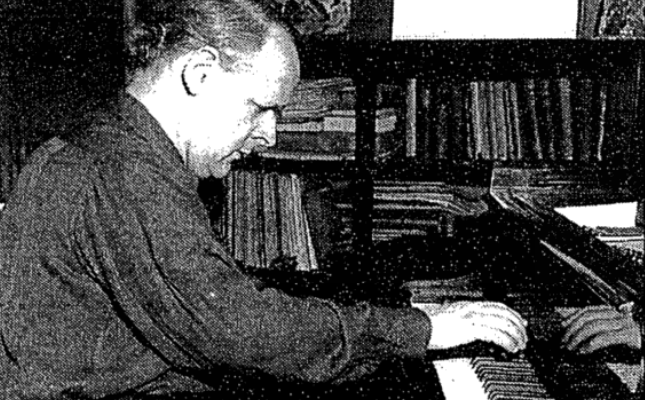

Hungerford started his studies at age 12 with Roy Shepherd at the Melbourne Conservatory, winning a full scholarship at the age of 17. Growing up in a small town some 70 miles away from this major city, he would travel to hear the greatest international artists who visited: pianists Moiseiwitsch, Schnabel, Backhaus, and Friedman, along with esteemed violinists Huberman and Menuhin, and great singers and conductors. He listened to the radio and read voraciously about the entire musical literature. He made his first radio broadcast at 18 and his concerto debut three years later with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra.

In 1944 he had some lessons with the legendary Polish pianist Ignaz Friedman, who had settled in Sydney when the war broke out, and Hungerford later stated that “there is no doubt that Friedman’s playing made a very big impression on me.” Determined to connect with international musicians to further his training and opportunities, he finagled his way into an audition with visiting conductor Eugene Ormandy – an important meeting that almost didn’t happen. During his visit in July 1944,

In 1944 he had some lessons with the legendary Polish pianist Ignaz Friedman, who had settled in Sydney when the war broke out, and Hungerford later stated that “there is no doubt that Friedman’s playing made a very big impression on me.” Determined to connect with international musicians to further his training and opportunities, he finagled his way into an audition with visiting conductor Eugene Ormandy – an important meeting that almost didn’t happen. During his visit in July 1944,

I tried to see Ormandy at a rehearsal, the guard said ‘no’ firmly. No autographs. I said I wasn’t after an autograph, I wanted him to hear me play. Which proved worse in his eyes. There were two doors of entrance. I skipped around to the other door, but he had beat me there. We dodged back and forth several times, but he always beat me. Finally, I went half way round and then turned back to the door I had left, sneaked in, dashed up some stairs and finally reached the stage. The guard dashed up to collar me, but Ormandy turned. I said: ‘Will you please hear me play?’ and Ormandy turned to the guard and said ‘This gentleman is only asking me to hear him play.’ I played.

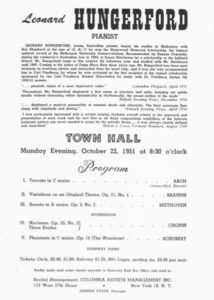

Ormandy was sufficiently impressed and suggested that Hungerford further his training with Olga Samaroff in Philadelphia; he would later arrange a scholarship for him to study at Juilliard with Hungerford’s compatriot Ernest Hutcheson – the dean of the college – once the War ended. Two days after Japan’s official surrender, Hungerford set sail on a 20-day voyage to Vancouver and then took the train to New York. His audition at Juilliard was before a panel of Ernest Hutcheson, Oscar Wagner, Rosina Lhévinne, Olga Samaroff, and Carl Friedberg. The young Australian would later hear that Friedberg had been overheard saying to Lhévinne, “I don’t know what that boy Hungerford’s doing studying here, he’s a finished artist.”

Hungerford was not particularly enamoured with Hutcheson: he admired him but didn’t feel inspired to push his own limits. He went to meet Ormandy backstage at a concert to ask for advice and in their few moments together the conductor suggested the pianist meet Samaroff to ask her thoughts. Hungerford did just that, and Samaroff was empathetic towards him, observing that so many teachers simply taught with a ‘one size fits all’ approach that doesn’t cultivate individuality. She suggested he finish out the year at Juilliard and then continue with her in Philadelphia the next year for a short while – which he did, beginning in October 1947. However, these too were unsatisfying: the lessons were short and infrequent (a half hour every two weeks), she was ill (which he didn’t know at the time), and he had just lost his own father, so this was not a particularly productive time.

Hungerford continued his search for the mentor he needed, writing to inquire about studying with Wilhelm Backhaus, who in early 1948 replied that while admiring Hungerford’s playing very much, his concert schedule made it impossible for him to teach anyone, also adding that he believed “you are well looked after if you study with Madame Olga Samaroff, and in fact I have the impression from your records that you are almost ready to be your own master.” It was around this time that the great Myra Hess – with whom Hungerford also had some coaching – suggested he study with Carl Friedberg. As he later recounted,

Early in 1948, I enjoyed the great good fortune of meeting Dame Myra Hess. The great lady graciously consented to listen to me play, and after I had played to her for almost an hour, I asked if she would advise me as to a teacher. I explained that I had been studying the piano for 14 years in Australia and the United States, and had worked with several pianists, all of whom were excellent, but to date I had not found anyone who had been able to help me towards a true understanding of Beethoven and Schubert, which was, and is, my main objective.

Dame Myra’s reply was: “Have you ever thought of working with Carl Friedberg?” This surprised me a little; I had often seen Mr. Friedberg at Concerts in New York and had always been struck by his gaunt and arresting appearance; I had never met him, but had spoken with many of his pupils, every one of whom I remember, revered him. I knew of his extraordinary cultural background, his having studied with Madame Schumann and his friendship with Brahms. I also knew of his eminence as a pianist and musician.

As I look back on it all now, my only regret is that I had not begun to study with Carl Friedberg long before this time. I think it must have been his great age, which subconsciously deterred me from doing so, and I remarked on this to Dame Myra. She said: “Yes, but he is incredibly alert and active and one does not have the feeling one is with an old person when with him. Besides, he loves his pupils, and all his pupils love him.”

The elderly German pianist and pedagogue asked him to play all the works he had played for Hess (she had apparently gone into a great amount of detail about his playing) and he immediately accepted him to start lessons the following week. Beginning the next academic year, he refused to take payment until sponsorship was found to cover his fees, and within the first two weeks of October he wrote to Hungerford to extend this offer as well as to the Australian Embassy to try to ensure that he would be allowed to remain in the US (he included Dame Hess’s name in his plea), as well as to patrons who might support him. Hungerford would be awarded the first annual Carl Friedberg Alumni Association scholarship, which funded 25 lessons with Friedberg. At the first of these, Friedberg “talked for quite a while first and said that he had given me this scholarship as he is convinced I have the goods. I am no longer a student but a master, and I am to converse with him now with that understanding.”

The elderly German pianist and pedagogue asked him to play all the works he had played for Hess (she had apparently gone into a great amount of detail about his playing) and he immediately accepted him to start lessons the following week. Beginning the next academic year, he refused to take payment until sponsorship was found to cover his fees, and within the first two weeks of October he wrote to Hungerford to extend this offer as well as to the Australian Embassy to try to ensure that he would be allowed to remain in the US (he included Dame Hess’s name in his plea), as well as to patrons who might support him. Hungerford would be awarded the first annual Carl Friedberg Alumni Association scholarship, which funded 25 lessons with Friedberg. At the first of these, Friedberg “talked for quite a while first and said that he had given me this scholarship as he is convinced I have the goods. I am no longer a student but a master, and I am to converse with him now with that understanding.”

With funding in place and an ongoing plan for their time together, the two evolved a wonderful working and personal relationship, something evidenced by the recordings of their lessons that Hungerford had fortunately had the foresight to produce (it appears he also recorded Friedberg’s 1951 Toledo performance of the Brahms 2nd Concerto). The tapes of these lessons reveal not only a good deal about Friedberg’s incredible wealth of knowledge – after all, he had trained with Clara Schumann and had been coached by Brahms – but also about the aged pianist’s admiration for the young Australian’s artistry. “You play this wonderfully, beautifully,” he’d intone with great kindness. As noted, he’d already felt that Hungerford was a highly capable artist at his Juilliard audition and still believed so when they began their lessons, and so Friedberg sought to give his pupil the required finesse to reach his full potential.

With funding in place and an ongoing plan for their time together, the two evolved a wonderful working and personal relationship, something evidenced by the recordings of their lessons that Hungerford had fortunately had the foresight to produce (it appears he also recorded Friedberg’s 1951 Toledo performance of the Brahms 2nd Concerto). The tapes of these lessons reveal not only a good deal about Friedberg’s incredible wealth of knowledge – after all, he had trained with Clara Schumann and had been coached by Brahms – but also about the aged pianist’s admiration for the young Australian’s artistry. “You play this wonderfully, beautifully,” he’d intone with great kindness. As noted, he’d already felt that Hungerford was a highly capable artist at his Juilliard audition and still believed so when they began their lessons, and so Friedberg sought to give his pupil the required finesse to reach his full potential.

The two developed and maintained their close connection, which lasted until Friedberg’s death on September 9, 1955. Hungerford played a memorial concert for his teacher about six weeks later, at Town Hall in New York on October 26, 1955, which is a wonderful example of his artistry and the earliest available recording to be released (it is unclear what happened to the recordings he sent Backhaus some years earlier). A letter sent to the pianist from one of Friedberg’s children indicates how pleased the late musician’s family was with the homage.

0:09 J.S.Bach – (after Marcello) Adagio in D Minor

4:18 J.S.Bach – Toccata in D Major BWV 912

16:03 F. Schubert – Impromptu in F Minor Op. Posth.142 No 1 (D. 935)

25:57 L. van Beethoven – Sonata No.32 in C Minor Op.111 (followed by a short spoken tribute and introduction to:)

52:44 Bach-Hess – Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring

In 1957 Hungerford gave a tour of his native Australia in which he played 33 concerts (both solo and concerto appearances), and a grant the following year from Mrs. John D. Rockefeller Jr. enabled him to tour Europe. Already engaged in his other great passion – he was a respected expert on ancient Egypt – and busy with his performing and teaching schedule, Hungerford would move to Southern Germany from 1958 to 1967 in order to focus his attention on his musical career.

It was at this time that he formally changed his name to Bruce, for both personal and professional reasons. He performed in Bayreuth (a superb Beethoven recital was recorded and posthumously issued) and there met the Wagner family, and he would make the first ever recording of the complete Wagner piano music (regrettably hard to find today). During his time in Europe he regularly played to sold-out halls, a level of success that regrettably eluded him back in the US.

It was at this time that he formally changed his name to Bruce, for both personal and professional reasons. He performed in Bayreuth (a superb Beethoven recital was recorded and posthumously issued) and there met the Wagner family, and he would make the first ever recording of the complete Wagner piano music (regrettably hard to find today). During his time in Europe he regularly played to sold-out halls, a level of success that regrettably eluded him back in the US.

He moved back to the States in 1967 after having been contracted to record the complete Beethoven Sonatas by Maynard and Seymour Solomon, founders and directors of the Vanguard Recording Society. He cut back somewhat on his performing schedule in order to focus on this project but also took on a teaching position at Mannes College of Music. The cycle was originally meant to be issued in 1970 but that was greatly delayed due to the pianist’s insistence that he become more familiar with the works he hadn’t yet played in concert and because he was not fully satisfied with the results of all of his sessions.

Sadly, Hungerford’s Beethoven cycle and what could have been a glorious career came to a tragic end on the night of January 26, 1977. He was returning home after giving a lecture about Egypt at Rockefeller University when a drunk driver drove into the car carrying him, his mother, his niece, and her husband of 3 months. All were killed. Hungerford was only 54 years old.

His Legacy

Hungerford’s rich musical legacy resides in his discography. In his 12 LPs for the Vanguard label, he set down 22 of Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas, in addition to one disc each of works by Schubert, Chopin, and Brahms. In addition to the private 1955 recording of his memorial album for his teacher Carl Friedberg, a number of live recordings have been issued by his pupil Donald Isler on his KASP label (all highly recommended – link here), including the only known filmed performance of Hungerford, a superb 1964 East Germany TV broadcast of Beethoven’s 4th Concerto.

A fine example of Hungerford’s way with Beethoven is this account the Sonata No.2 in A Major, Op.2 No.2. Even as he delivers the stark dynamic contrasts so idiomatic to Beethoven’s music, he sustains beauty of tone, also highlighting the varied moods with mindful articulation and judicious use of the pedal.

An excerpt of Hungerford’s filmed performance of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.4 in G Major Op.58 is shared here via the Facebook page of Meloclassic, who first unearthed the footage. In this passage featuring the cadenza and closure of the first movement, Hungerford plays at a brisk pace and with depth and passion that embody the revolutionary spirit of the composer. Click this text to view the excerpt.

Chopin was another composer with whom Hungerford was ideally suited, well served by his lessons with Friedman and Friedberg, the latter a greater Chopin interpreter than might be thought. However, Friedberg did not always condone Hungerford’s Cortot- and Friedman-influenced approach to Chopin: he once gently chided his student, “Oh, Leonard, I heard Rubinstein play the Andante Spianato and Grand Polonaise last night. You would have loved it! He had 22 different tempi!”

Hungerford’s big-scale recording of the Sonata No.3 in B Minor Op.58 is characterized by his forged phrasing’s legato lines, depth of tone, and elegantly coordinated rubato.

On October 3, 1970 Hungerford was one of the many illustrious pianists to appear at the International Piano Library’s benefit concert at Hunter College. This recording finds him playing some Schubert Ländler not in his official studio discography (this appears to be a different selection from his Vanguard outing) and is of significant interest because, like many artists, Hungerford could at times be more restrained in the studio. This concert tape captures his refined and impassioned playing at its most inspired, with sumptuous tone, seamless legato phrasing, and wonderful rhythmic vitality.

Hungerford was naturally a great proponent of Brahms, in no small part due to his tutelage with Friedberg. This performance of the Capriccio in B Minor Op.76 No.2 features a wonderful balance of seamless phrasing and detached articulation to highlight both the lyrical and playful characteristics of the work.

The final musical selection of this post is a particularly moving one: a performance of the Bach-Hess Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring that was the final encore he played at his last recital, in Calgary on December 8, 1976. The entire concert was a tribute to his mentor and friend Dame Myra Hess and the official radio recording ended up being broadcast for the first time after the pianist’s death a mere six weeks later – the full recital is available on KASP Records here. This lovely performance reveals Hungerford’s sumptuous phrasing, beauty of tone, steady rhythmic pulse, and layered voicing – as well as his humming at a few moments.

Finally, for those who would like to hear more recordings and personal accounts of the artist, a two-part radio program tribute to Hungerford featuring three people who knew the pianist well, Robert Lurie, Werner Isler, and Gary Klein.