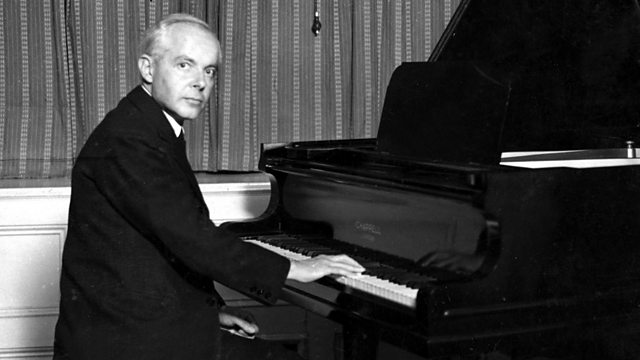

The legendary composer Béla Bartók was a superb pianist, but his standing as an interpreter has often been overlooked due to his fame as a composer. Those who are more familiar with him in the latter role might be unaware that he studied with István Thomán, a pupil of Liszt, and placed second at the 1905 Anton Rubinstein Competition (Backhaus came first), and he maintained his remarkable capacity as a performer through his life. György Sándor said of the composer’s playing, “Bartók was technically a virtuoso on the level of Prokofiev, Dohnányi, Rachmaninoff, and Busoni. And as an interpreter, there are no words to describe the fusion of his world with that of the composers he played. Sequences of notes were turned into richly expressive melodies, harmonies and chords were bursting with tension or brought soothing relief. His rhythms danced with grace or angularity. His Scarlatti, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Debussy were highly personalized and filled with the spirit and pulsating life of the creative instinct….”

There are a good number of recordings of the composer playing his own works, which are insightful in and of themselves, and we are fortunate to also have some superb recordings of him in a wide range of repertoire that would be surprising to those only familiar with his compositions: tantalizingly brief but revelatory accounts of Scarlatti, Liszt, Brahms, and Chopin, among others. All of these reveal that he was an absolute master at the piano, both in execution and conception. Unfortunately the majority of these performances were not issued beyond the brilliant releases produced on the Hungarian label Hungaroton, which means that they have escaped the notice of many students, teachers, and pianophiles who would surely be fascinated by these recordings.

Fortunately, YouTube has made easy access to some of these historical documents far easier, and a dedicated study of this brilliant musician’s piano recordings should be undertaken by anyone interested in the art of musical interpretation. While this page is not an exhaustive survey of Bartók’s pianism, it is an introduction to some of the recordings that are ‘must hear’ aspects of his discography that can provide great insight into his pianistic and interpretative genius. .

To begin, a 1929 recording of four Scarlatti Sonatas – K.427 (L.286), K.212 (L.135), K.537 (L.293), and K.70 (L.50) – a concept that might not compute for many. These incredible performances demonstrate terrific pianism on every level: even when playing at a rapid pace (as he does in the first), we can hear beautiful tone, precise and varied articulation, clear sense of rhythm, layered voicing, and impressive dexterity.

Here is a performance that I consider to be absolutely revelatory: Bartók and his wife Ditta Bartók-Pasztory playing Mozart’s Sonata for 2 Pianos K.448. The composer had in fact edited 20 Mozart Sonatas (as well as the Well-Tempered Clavier and 19 Haydn Sonatas), something that those who only know him as a composer might find surprising – and the same applies to his playing, as there is the assumption that his interests were limited only to his own revolutionary music. This amateur recording of an April 23, 1939 broadcast of the great husband-and-wife duo was made off-the-air by engineer István Makai, who did not yet have a double-turntable set-up to record seamlessly (as he did in the Brahms featured below), so the recording has a couple of gaps when the 78-rpm discs reached their time limit and needed replacement – and unfortunately the end is lost. Nevertheless, this performance makes for fascinating and absolutely essential listening. While the limited sonic range of the recording limits full apprehension of the pianists’ glorious playing, we can still appreciate their marvellous tonal colours, wonderful phrasing, rhythmic vivaciousness, interesting and effective accenting, and clarity of texture.

Bartók plays with the same exquisite clarity and precision in Beethoven too. A live 1940 recording of the last movement of the Kreutzer Sonata, with Bartók’s compatriot Joseph Szigeti on the violin, circulated a bit more widely in the West and it should certainly be required listening for all musicians. In the last movement presented here, we can marvel at the pianist’s great beauty of tone and wonderfully shaped phrasing, but there are more subtle elements in the cohesiveness between these two musicians and the declamatory style in their individual playing.

The contemporary nature of Bartók’s own compositions can make the thought of him playing Romantic repertoire seem virtually unimaginable, but his interpretations of works from this era were legendary during his lifetime. One of the performances that best demonstrates his mastery in this realm is an otherworldly 1939 off-the-air recording of Chopin’s Nocturne in C-Sharp Minor Op.27 No.1. Unfortunately the closing section of this radio performance was not recorded, but even in the first few seconds one is aware of the musical genius on display: at an incredibly spacious tempo, Bartók sustains the primarily melodic line with a magical interplay with the undulating accompaniment in the left hand, his remarkable pedal technique and tone production together creating an atmosphere of astounding depth.

Bartók’s 1936 recording of Liszt’s Sursum Corda from the Années de Pèlerinage reveals dramatic inflection and projection of sound, with a full-bodied sonority (that bass sound!), effective use of pedal, and attentive voicing. Apparently his playing of the Liszt Sonata in B Minor was stupendous, and hearing the present performance makes it all the more tragic that no recording of him playing that work has been found.

In a private recording of Bartók playing the Brahms Capriccio in B Minor Op.76 No.2, we can hear all kinds of remarkable details: beautiful voicing, varied articulation that shapes phrases to perfection, a delightful rhythmic bounce, transparent layering of lines, seamless legato, idiomatic rubato, and – appreciable despite the poor recording quality – an utterly gorgeous tonal palette.

Fortunately some unofficial recordings of the composer playing larger-scale works other than his own exist, one of the most fascinating being a performance with his wife Ditta Bartók-Pasztory of the Brahms Sonata for Two Pianos Op.34b (this was a reworking of an earlier [now lost] F Minor String Quintet, and though the known Brahms Quintet was arranged after this Sonata, it was published first). This October 1939 broadcast recording of the pianists is an extraordinary document capturing some astounding pianism, with clear lines, beautiful highlighting of harmonies, rhythmic vitality, and wonderful ensemble.

Andor Földes used to tell the story of Bartók advising a student playing his Sonata to ‘play it a little less Bartók-ish’, suggesting that even in his lifetime there was the tendency to play his music aggressively. Listening to his own recordings is revelatory as it becomes clear how his music can be played without harshness – and what a different quality it takes on when performed in this way. This 1940 performance of the Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm (dedicated to Harriet Cohen) from Mikrokosmos Volume VI captures in very fine sound Bartók’s rhythmically vibrant and tonally rich pianism in his own music. Notice that even when he plays pronounced accents, he never breaks the line or compromises tonal beauty. It is remarkable to hear him play with vitality but without banging, emphasizing certain beats without distortion or harshness, all while still sustaining a line.

Also from from Mikrokosmos (Book IV), the Notturno (No. 97) is heard here in a 1940 recording that reveals the same beautiful sonority, legato phrasing, and transparency of texture that we could hear in his Liszt. What a gorgeous tonal palette, clear voicing, attentive accenting that does not break the line, and marvellous timing – truly magical, evocative playing.

Unfortunately we don’t have official recordings of Bartók playing his works for piano and orchestra, but nearly 17 minutes of a March 22, 1938 concert of his 2nd Concerto was recorded. We should really consider this to be the miracle that it is as this performance, like so many, could have simply disappeared into thin air. Recorded live at Vigadó, Budapest with Ernest Ansermet conducting, these precious excerpts reveal, despite the faded sound and prominent crackle of the amateur discs, a distinct lack of aggression and harshness on the part of the soloist: with attentive listening, we can hear how clearly Bartók voices harmonies, and how even when his tone is strong there is no brittleness to his approach. A truly precious historical document that requires some patience to listen to but which provides invaluable insight into the composer-pianist’s conception of this phenomenal work.

While Bartók’s position in musical history as a great composer is entirely secure, it is to be hoped that he will also take his rightful place in the pianistic pantheon as an performer of the highest calibre. Over a century after many of his compositions opened up a world of new possibilities, listening to his performances at the piano can bring similar expansive perspectives, not just for the interpretation of his music but the entire realm of piano repertoire.

One comment

A very comprehensive introduction indeed, congrats Mark Ainley! Did you know that the opening ff chord of the third movement in the Kreutzer Sonata was actually played by an unknow pianist? this wonderful recording lacked that very bar, apparently!