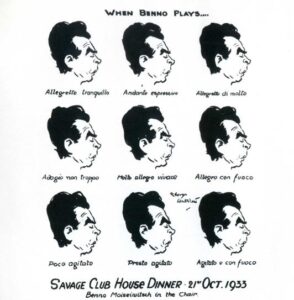

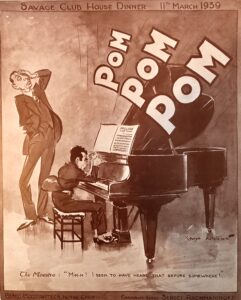

We live today in an age of exaggerated showmanship, where many less cultivated pianists believe that they must demonstrate emotion rather than convey it directly through their playing. The demeanour of Benno Moiseiwitsch was, by contrast, one of unpretentious certainty: he was an aristocratic pianist who, despite his poker-faced appearance at the keyboard, brought warmth, elegance, beauty of colour, and depth of emotion to his interpretations.

We live today in an age of exaggerated showmanship, where many less cultivated pianists believe that they must demonstrate emotion rather than convey it directly through their playing. The demeanour of Benno Moiseiwitsch was, by contrast, one of unpretentious certainty: he was an aristocratic pianist who, despite his poker-faced appearance at the keyboard, brought warmth, elegance, beauty of colour, and depth of emotion to his interpretations.

The illustration on the right shows the extent to which his controlled appearance was well-known, the great Russian pianist depicted with the same facial expression for 9 different tempo markings commonly found in music. Not that he ever played a composition the same way, but his appearance did not reveal what he was communicating – that was for your ears to hear. With a career that spanned half a century and many hours of recordings made over nearly the same period, Moiseiwitsch was a pianist whose artistry has stood the test of time and is still very much appreciated today.

Humble beginnings

Benjuma Moiseiwitsch was born in 1890 in Odessa, the birthplace of so many great pianists (Cherkassky, Barere, Grinberg, Pouishnoff, de Pachmann, and Feinberg, for example). His was a large family – 6 brothers and 2 sisters – and it was his mother who first became aware of his musical talent. When the boy was spontaneously playing melodies on the piano, she told him that there was a way to read the songs he liked at the piano and asked if he’d like to learn – and the answer was an enthusiastic yes. He could recognize and articulate the emotional character of music to the degree that his mother decided he must have a better teacher. His father put him to a test that might have been a first step in developing the confidence he demonstrated on stage: if he were to agree to pay for lessons, Benno had to play him something, but he began to do so nervously. His father told him that he needed to play confidently: “Play that piece again and this time forget that I am judging you. I am of no consequence if what you say is right and you believe in it.” Benno’s second performance was altogether different, convincing his father to arrange for his private lessons to start the next week.

Dedicated individuality

The young boy’s confidence was now such that his teacher soon complained that he played things that weren’t written and not always the same way. The young Benno argued, “You can say things different ways, can’t you? The same words can have different expression. It’s dull doing them always the same way… Some things seem to be me different on different days.” When his father argued that the composer put certain things in the score for a reason, Benno mindfully answered, “But he’s different from me. He may have felt it one way; I feel it my own way. I would like to play always just the way I feel is right.”

This does not mean that the young musician did not recognize that there was more to music than his personal sense. When he first started playing Mozart, he was aware that something was missing in his approach. Benno found Mozart’s music to be like a man skating on ice: “He makes figures, and the figures get more and more complicated; but he does it all for a reason.” The family entered into a great debate as to which approach he should take, his engineer brother suggesting he just let the music play itself, his mother feeling the emotion was the key. The next morning Benno’s playing woke up the whole family – the maturing musician had figured it out.

For all his dedication to his craft, Benno’s combination of nonchalance and good humour was a predominant characteristic trait from a young age – not always to his advantage. He got in trouble early on for making fun of his first piano teacher (he composed little ditties that imitated how he spoke) and in school he was constantly being reprimanded for his practical jokes. But he certainly excelled in his schoolwork with a casualness that belied his family’s more emotional nature. When he was at the breakfast table and his parents asked who had won the prestigious Rubinstein Prize at the Imperial School of Music the previous day, the young lad replied, between bites, “Oh, I forgot to tell you – I did!” His apparent indifference was in stark contrast to the emotional eruptions that ensued amongst the family. He had won for his “brilliant and individual playing,” qualities already evident at the beginning of his lessons and that would be hallmarks of his performances for decades to come.

An impresario came soon after expressing interest in a tour but Benno’s father quickly saw a flaw in his approach that led to the family’s initial enthusiasm changing tone: the pianist was booked on the basis of his prize win but the agent didn’t ask to hear him play. “He’s not really interested in my son. He’s interested in a newspaper story.” And so Benjuma’s performing career would be somewhat delayed – as was his schooling. While Benno was still getting in trouble as a practical joker, things took a more serious turn when he was falsely accused of a more serious indiscretion – which, for a change, was actually not his doing – and as a result he was expelled. The 15-year-old was sent with his eldest brother to London to apply to the Royal Academy of Music – but once there, he was not admitted because he was too advanced! But the trip was not without merit, as the head of the school – one Dr Cummings – was considerate enough to refer him to the great Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna.

Studies with Leschetizky

Benno’s uncle Sasha – his sister’s husband – arranged for the teen to play for the legendary master in Vienna but his first audition did not go well. Benno had chosen to include Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude, but the master was hardly complimentary: “I can play this better with my left foot. There are a hundred delicate nuances in the piece which you’ve sacrificed for effect. I don’t want bravura or exhibitionism.” He told Benno to go practice for a couple of months and to return when he’d “mastered real control.”

Although Benno was dejected, Uncle Sasha astutely pointed out, “We haven’t come all the way from London to Vienna in order to be told that you play perfectly. What would be the point – from a teacher?” Encouraged by his uncle’s wisdom, Benno worked eight hours a day for the following two months and when he went to play for Leschetizky again, he was immediately accepted: “You’re no longer a ‘gifted amateur,’ young man. You’re beginning to hear yourself seriously.”

Benno’s four years with Leschetizky formed him as an artist, teaching him to listen to himself accurately. In an interview decades later, Moiseiwitsch stated that the Viennese master’s reputation as a great teacher of technique was not quite precise: “With him, it was colour, and he tried to instil musicianship into the artist … naturally you have to have a certain technique as a means to an end, and that he kept emphasizing.” Leschetizky also encouraged this particular “natural-born Romantic” to approach different composers with the appropriate mood, which led to Benno playing with a more detached, less sentimental style. His natural tendency had been to “see music in emotional terms – storms at sea, great dramas, sad events, tender love, lingering farewells, and so on. [Leschetizky] corrected this tendency and at the same time gave my playing an extra dimension, an awareness or recognition of what may be called intellectual passion.”

Beginning his career

When Leschetizky decided he had nothing more to teach Moiseiwitsch – that anything else he needed he had to learn on his own – the young Russian man joined his family in London to arrange his debut. They knew nothing about how to go about this and wryly noted that the only people going to debuts were “relatives and enemies.” Uncle Sasha suggested Benno’s scientific brother John approach the problem with his unique perspective and he came back with a solution: that the pianist give a joint recital with an established artist – one who was not a pianist. The one they decided upon was the famous singer Dame Nellie Melba, who appears to have been very impressed by the young pianist at the social event at which they were introduced. It appears that this joint recital took place before a small audience in Reading on October 1, 1908.

Benno’s own actual solo debut took place at the Bechstein Hall (now Wigmore Hall) on February 8, 1910: he had programmed a few ‘easier’ pieces early on in order to let himself get comfortable, which was a good idea as he was immediately struck by the strong lights, which led him to perspire a great deal. The programme was quite an impressive one: Bach’s Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata, Schumann’s Carnaval, Chopin’s Sonata in B Minor, and Brahms’ Paganini Variations (a selection he would repeat 25 years later at a concert at the London Palladium celebrating his quarter century on the stage). The concert went very well, the reviews the next day were very positive, and Moiseiwitsch’s career was launched. That year, he would give his first Promenade concert under the baton of its founder, Sir Henry Wood, and he would be a favourite of the series, playing a total of 95 times from his first invitation through to 1962, the year before he died.

In 1914 Moiseiwitsch married Australian violinist Daisy Kennedy. The two were a fine match not only because of their musical abilities but due to their sense of humour and a range of character traits. They had been introduced in Vienna by friends who thought they would make a fine couple and they hit it off from the get-go. They had two daughters (Tanya [1914-2003] and Sandra [1922-1996]) but the couple drifted apart: Benno enjoyed going out in the evenings to meet his friends, and Daisy had given up her performing career for family life. She began to meet with a different circle of friends, through whom she met and then fell in love with English playwright and poet John Drinkwater.

Their divorce was a blow to Moiseiwitsch, who abstained from dating for some time, despite many suitors. His approach to relationships, while definitely rooted in older traditions, was still philosophical and musical in nature: “One tries to make a work of art with a human relationship, which is after all the most sacred thing there is. Sometimes it can only promise to be a minor work… but one thing one learns from experience is that all preconceived notions as to how to play the score are useless.” He eventually met his second wife, Anita, whom he would marry in China in 1929 and whose son Boris [b.1932] became a New Zealand broadcaster. Benno remained very devoted to Anita until her death from cancer early in 1956 – a loss from which he would never fully recover.

Worldwide success

Moiseiwitsch would remain in England and tour all over the world for decades: at least twenty visits to the US, six to Australia and New Zealand, four to South America, three to the Far East, and he was very warmly received by audiences and critics alike. Publicity material from his agents in the 1920s state that “Minneapolis is hardly notorious for its excitability but the ovation accorded Moiseiwitsch there on his last American tour resembled a riot. Even after the great pianist had played innumerable encores, the crowd followed him to his car, and the press of the excited, milling mob was so terrific that the windows of his car were broken in.”

Strangely, Benno was never invited as soloist with the New York Philharmonic, although he gave frequent performances in the city (his US debut was at Carnegie Hall, and his recitals there featured some jaw-dropping programming). How a pianist who was as respected by Hofmann (who invited him to be on the faculty at the Curtis Institute) and Rachmaninoff should not be invited by the major symphony orchestra in a city he regularly played in is virtually incomprehensible.

It was in fact in New York – in 1919 – that he would first meet his idol Rachmaninoff, whose music he loved and played with great success. He was in awe of his older compatriot, who also admired Moiseiwitsch’s playing of his music, and the two developed a tight bond when they discussed a work of the famed composer that it turned out was a favourite of both musicians. Moiseiwitsch recounts the tale in this interview filmed in the last decade of his life:

Moiseiwitsch’s mastery of Rachmaninoff’s idiom is evident in all of his recordings of the composer’s works – indeed, Rachmaninoff called him his “spiritual heir.” His 1940 recording of the Prelude that forged their connection is truly marvellous: his magnificent tonal palette includes a brooding bass and rich singing treble, and he balances voicing between hands with remarkable skill, creating a melting effect with his emphasis and phrasing that adds even more melancholy to his performance.

Having lived in London for so many years, Benno became a British citizen in 1937 and was made Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1946 for his active role in playing not only at Dame Myra Hess’s wartime concerts at the National Gallery but also some 800 other performances for servicemen and charities.

In addition to his professional activities and family life, he enjoyed fine dining, horse races, and poker. Jascha Spivakovsky’s son Michael recalls that when Moiseiwitsch visited the family in Melbourne in the 1950s, he practiced on the music room Steinway with the racing papers propped up on the chair next to him. Benno also regularly played cards with his friend and colleague Solomon, whose career had come to an untimely end due to a stroke in 1956.

Having a discerning appreciation of cigars and drink (creme de menthe was apparently his secret weapon for playing the 19th variation of Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody so well), Benno’s health was not always robust and heart issues became more troublesome in the last decade of his life, at which time some lapses in his previously flawless pianistic precision became evident; his exhausting schedule was also beginning to catch up with him. However, he could still pull out the stops and play tremendously well, as he did at his last Royal Festival Hall performance of March 6, 1963, when he gave a rousing performance of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto (issued by the BBC) that demonstrates undiminished strength and sensitivity. He died less than a month later, on April 9, 1963 at the age of 73.

Moiseiwitsch’s pianism

Fortunately, Moiseiwitsch made a great many recordings and they are being issued systematically on the Naxos label at very reasonable prices and in wonderful sound. Having set down recordings over a fifty-year period – plus a great many unofficial concert performances having been issued – Moiseiwitsch has a more comprehensive recorded legacy than many of his contemporaries and he is one of the most satisfying pianists on record. His performances are overflowing with elegant phrasing, creative highlighting of melodic and harmonic content, exquisitely refined nuancing, and magnificent tonal colours, appreciable even in earlier discs with much less sonic fidelity than those made later in his career.

Fortunately, Moiseiwitsch made a great many recordings and they are being issued systematically on the Naxos label at very reasonable prices and in wonderful sound. Having set down recordings over a fifty-year period – plus a great many unofficial concert performances having been issued – Moiseiwitsch has a more comprehensive recorded legacy than many of his contemporaries and he is one of the most satisfying pianists on record. His performances are overflowing with elegant phrasing, creative highlighting of melodic and harmonic content, exquisitely refined nuancing, and magnificent tonal colours, appreciable even in earlier discs with much less sonic fidelity than those made later in his career.

His technique was utterly remarkable but also completely transparent, dexterity never a goal unto itself but always at the service of the music: as he said in a 1950 essay entitled ‘Playing in the Grand Style’, “technical matters … can be learned at any hour of the day. The problem facing the young pianist is not how to play faster and louder, but how to play music in moving and musicianly fashion. This he can accomplish by breaking away from a preoccupation with mechanics, and by concentrating earnestly, devotedly, independently upon musical thought- as was the habit in the ‘grand’ days.”

Moiseiwitsch did not win over all critics, however: at times his patrician approach was too cool for those who wished for more overt displays of passion, as in his traversals of Tchaikovsky’s First and Second Piano Concertos. There was an added factor due to which Moiseiwitsch seemed not to garner respect from all: in the UK, his HMV records were issued on the Plum label, reserved for local artists, and there were those who saw it instead as signifying that he was not a performer of international standing – which of course was far from the truth.

The pianist’s poised interpretations are a result of a wonderful balance of intelligence and emotion, a point he articulated quite beautifully in the aforementioned essay: “I am startled, occasionally, to find “intelligence” used as the antithesis of “feeling”, as though the two played against each other. Nothing could be further from the truth. No intelligent interpretation is lacking in emotional values. What this probably means is that, depending on gifts and degree of maturity, some natures emphasize brain over heart. Where such an imbalance occurs, it must be corrected by conscious and concentrated application to emotional content. If an interpretation is unduly cerebral, liveness and colour can be infused into it by attention to whether the theme is now in the right hand, now in the left; whether it is supported by an accompaniment which has significance of its own, or merely hums along.”

Moiseiwitsch began making records in 1916 and was with the HMV label until 1961, when he produced three stereo discs for Decca while in New York, records which were noted by some critics to show signs of imprecision and aging; nevertheless, these do feature some fine playing (they are certainly more stable than most of Cortot’s later recordings) and present him in some works that he had not previously recorded, such as Schumann’s Carnaval and Beethoven’s Les Adieux Sonata.

His earliest records consist mostly of shorter compositions that fit on one side of a 78rpm disc (between 4 and 5 minutes), although he did attempt what would have been the world premiere recording of Chopin’s Preludes across several discs but it was not to be: he made attempts at the set in 1921, 1922, and 1924, but none of these takes were issued and he would not actually set down an account until 1948/49 – about a quarter century after his first attempt (as it turns out, it’s one of the greatest cycles on record – though the contemporary Gramophone review was rather tepid in its assessment).

One wonderful early acoustical (pre-microphone) recording is reading below of two works rarely heard today, Palmgren’s Finnish Dance and Leschetizky’s Arabesque in A-Flat, put on disc on September 19, 1921. (It’s interesting that his name is spelled ‘Moiséivitch’ on the label, as it was on a few early records.) Despite the limited sonic fidelity, we can appreciate Moiseiwitsch’s clarity of touch, transparent textures, evenness of articulation, and fluid phrasing.

Once electrical technology (i.e. the use of the microphone) came into effect in 1925, Moiseiwitsch began recording a few longer compositions, setting down readings of Schumann’s Kinderszenen and Brahms’ Variations on a Theme of Handel in 1930 (he’d attempted the latter twice in 1925 – once acoustically, the second electrically, but neither issued and no copies of these have been found). The latter is in particular a stunning performance (his 1953 version is stupendous as well), filled with fire that is tempered by his refined phrasing and beauty of tone: he never sacrifices purity of sound for power, creating a booming effect in the bass by producing a deep but not loud sonority with a texture so transparent that travels through all registers, resulting in a greater sense of strength and grandeur that many lesser pianists attempt to achieve through external force alone. His fluidity of phrasing and the burnished singing quality of his touch are absolutely mesmerizing:

Although known for his readings of Romantic repertoire, Moiseiwitsch did explore a few of his contemporaries’ works, playing a few shorter compositions by Ravel, Debussy, Prokofiev, and Stravinsky (it’s remarkable to think that this was new music at the time he was playing it). His 1928 reading of Prokofiev’s popular Suggestion Diabolique Op.4 No.4 is a terrific performance, played with vitality and gusto, with rhythmic freedom and less incisive articulation than we often hear today – similar to how the composer himself played it:

Beethoven was close to Benno’s heart and he regularly programmed his concertos and sonatas (and recorded some too). His approach to the composer’s oeuvre can be clarified in this wonderful quote, with his usual tongue-in-cheek slyness: “The romantic pieces, Leschetizky told me I ought to play in a classical style, and the classical pieces, by special indulgence, in a romantic fashion. Now Beethoven is both; but as some pieces are more romantic than classical, these I play in my classical-romantic style; whereas those that I are more classical than romantic I play in my romantic-classical style. You’ll forgive me if I get a little confused sometimes and just play the way I feel.” This concert recording of the last movement of the Waldstein Sonata comes from a private source given to me in Tokyo in 1992, recorded during Moiseiwitsch’s 1958 tour of Japan – the rest of his performances have not been found and this has not been issued anywhere. Although his technical certainty wanes at moments, the beauty of his performance and the magic of hearing this pianist in concert outweigh any lapses in precision:

One of his most famous recordings – and justly so – is his March 17, 1939 account of Rachmaninoff’s transcription for piano of the ‘Scherzo’ from Mendelssohn’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream.’ It is a treacherous work that requires phenomenal fingerwork to play successfully. In the early days of recording, choosing what work to record was subject to many conditions, not least of which was what other performances had been issued on other labels. Because Rachmaninoff had already recorded the work on RCA, Moiseiwitsch’s label HMV (the UK sister-label to RCA) was reluctant to record a performance that would compete with the composer’s own.

One day, at the end of a recording session, producer Walter Legge informed Moiseiwitsch that they still had some time left on the clock and suggested recording a short work to keep on reserve. The pianist, being quite tired, didn’t particularly want to play anything else – and he’d already started putting the collar back on his shirt (as one apparently did back in the day) – so he suggested Rachmaninoff’s Mendelssohn arrangement, thinking Legge would refuse… but the producer called his bluff and accepted on condition that Benno make only one take, thinking of course that the pianist couldn’t do it and so they wouldn’t have to issue the recording. (In those days, performances were cut directly into wax and could not be edited. Rachmaninoff made at least six takes of the work in his sessions to produce a version that satisfied him.)

The pianist no doubt smirked at the challenge, and then sat down at the piano and made a truly jaw-dropping traversal of the piece, note-perfect and pianistically magnificent: a resonant tone even in soft passages, remarkably even fingerwork, and incredible consistency of articulation and speed. It is generally considered to be even better than the composer’s own account and Benno himself stated that he thought it was his greatest recording.

For all of the incredible discs that Moiseiwitsch made, he didn’t particularly enjoy the recording process, finding the pressure of the red light and need to produce a ‘perfect’ 4-to-5-minute take restrictive (though he certainly managed to do so more often than not); while he felt there was some improvement with the possibility of tape editing, he still preferred complete performances – he was one of the many musicians whose artistry was even more communicative while in concert performance. The 1946 BBC broadcast below of Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini is better than both of his studio efforts and is a truly special performance.

This recording is particularly close to my heart and has quite a background story. I obtained this on cassette in the late 1980s in a trade with a fellow in the United States. Although Benno’s two studio recordings of the work are quite wonderful, this performance is truly on another level, with nuancing of such utterly exquisite refinement that it leaves the listener breathless. I sent a copy to Bryan Crimp, who had at that time released two sets devoted to the pianist on his then-recently-formed APR label: he was so taken with it that he sent it to the pianist’s daughter Tanya, who declared it the greatest performance of her father in the work that she had heard. I also sent it to Gregor Benko of the International Piano Archives, who was equally effusive in his praise (he recently stated that it is one of his favourite recordings of anyone playing anything).

In 2011 the performance was issued on the Testament label, and it turns out that my cassette was the source: Ward Marston had provided his copy of the performance, which was derived from Benko’s copy, which came from me (this was unknown to Ward and the producers, who credited Ward in the booklet). Fortunately, master source material has since been located and the recording is now available in truly pristine sound quality (for a 1946 off-the-air broadcast!) on Marston’s own label, in the 3-CD set that features the recently discovered recording of Rachmaninoff playing in Eugene Ormandy’s living room (click here) – a release that I cannot recommend highly enough (as would be the case even if just for the performance below).

Despite his reticence about recording, Moiseiwitsch still created discs of astounding beauty, revealing his mastery in readings of works that can be played technically perfectly by far lesser pianists but not with the fully multidimensional approach he brought to his interpretations. This Chopin Nocturne recorded in 1952 is one of the more ‘simple’ ones of the genre – commonly played by students – but what mastery we hear in every second of this reading, with a beguiling singing tone and sumptuous nuancing. One never knows how or when he will adjust dynamics, timing, or colour, but whenever he does, one marvels both at the beauty of Chopin’s writing and the mastery of Moiseiwitsch’s pianism – a perfect union between composer and interpreter, an ideal balance between objectivity and personality. Every note sings and every phrase is lovingly shaped in a performance that is jaw-dropping in its beauty:

Schumann was Moiseiwitsch’s favourite composer, and each recital featured at least one of his compositions. While he did not make grand undertakings of his works in the studio in the 78rpm era – Kinderszenen and some shorter works only – in the 1950s he set down stellar accounts of the Fantasie and Fantasiestücke for EMI, followed by readings of Carnaval, Kreisleriana, Kinderszenen, and the Arabeske in his 1961 Decca sessions. (He had played Carnaval, Kreisleriana, and the Etudes Symphoniques in New York recitals around the time of these sessions.) While those final recordings and recital performances do not capture his playing at its most refined (the studio versions are still quite fine), his EMI accounts most certainly do, the Fantasie being particularly admirable for its stunning tonal colours, soaring phrasing, and refined dynamic layering and pedalling – a titanic traversal set down in a single July 20, 1953 session by the 63-year-old pianist:

Fortunately Moiseiwitsch lived long enough to be filmed, though we regrettably do not have as much as we might hope. He made his first BBC television appearance on March 14, 1938 and filmed another broadcast that November, in addition to several the following year – including a performance of the Mendelssohn-Rachmaninoff Scherzo just a few weeks before making that famous record discussed and linked above. After the war, his appearances resumed with one legendary performance linked below and more appearances that unfortunately seem not to have survived, among them complete traversals of Carnaval in 1956 and Pictures at an Exhibition in 1957.

Fortunately his November 3, 1954 BBC broadcast was preserved and released on DVD (though as an appendix to a disc devoted to another artist). The piece he played is the treacherous Liszt arrangement of Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture, a work so challenging that the composer himself used to take a break midway through. The performance here is shot with a sole camera that zooms in slowly over the course of the 15 minutes, and one can watch in amazement as the 64-year-old Moiseiwitsch overcomes the considerable technical hurdles of the piece without a single grimace. While this reading may not meet today’s standards of clinical note-perfection, one would struggle to find a performance that has this level of tonal range, grandeur, and abandon – keep in mind that every modern commercial recording that you hear is made up of multiple edits sliced together. There is never an unnecessary movement (his dramatic-looking arm drops are for tone production): he plays with pure economy of gesture, but also with full emotional, tonal, and dynamic range. And at the end, a farewell message that demonstrates his suave character. A gentleman and aristocrat, at the keyboard and in life.

Comments: 2

Merci Mark. C’est véritablement hallucinant. Mais en même temps quelle profondeur !

Oui, tout a fait… un artiste unique, un de mes favoris…