With the advent of the CD in the 1980s, historical recordings began being made available at a faster rate than ever before, and as a result we are today able to hear more great artists of the past than at any other time. Now with the internet and YouTube, we are able to enjoy the playing of musicians who have been overlooked by the recording industry but whose music-making warrants attention.

Since starting my Facebook page in 2009, I have discovered many pianists whose artistry I hadn’t previously known simply by scouring YouTube and other sites that feature uploads of recordings, both commercial and unissued. I still recall my impressions when one day I came across a performance of Chopin’s Etude Op.10 No.4 by a pianist that I’d never heard of before, one Sidney Foster. I was blown away not only by the impeccable dexterity and clarity of his playing but also by a truly incredible personal touch: the addition of some notes in the left hand that continued the melodic line of Chopin’s composition – a truly brilliant, insightful, and musical adjustment to the score (heard starting at 1:07 in the clip below).

There were a few more Foster uploads on YouTube and I found all of them to be extraordinary. With a bit more searching online I discovered that the International Piano Archives at Maryland had issued a 2-CD set of concert recordings by the artist; anything produced by IPAM would obviously be of the highest standard, so naturally I ordered the set and once it arrived was absolutely thrilled by what I heard. Even in works as overplayed as Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata, Foster could make things sound new without any exaggerated nuancing or indulgences: you could take dictation of the score from his performance, yet it was fresh and alive.

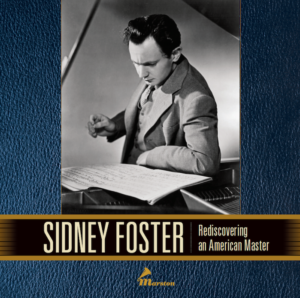

While many criticize Facebook for its negative impact on society and communication, for me it’s been a truly amazing vehicle to connect with wonderful people in the music field; one of these is Foster pupil Alberto Reyes, himself a wonderful pianist whose performing career was placed on the back burner while he worked for decades as an interpreter at the United Nations. On my 2014 visit to New York, Mr. Reyes invited me to lunch and we had a truly engaging and insightful conversation about music-making and his beloved mentor, whom he continues to idolize (rightly so) and about whom he has spoken and written with great eloquence. Reyes was the driving force behind an incredible production that has since been released on the Marston Records label: a centenary tribute to Foster featuring 7 CDs of concert and broadcast performances, every single one of which is top-tier. In addition to these ten hours of stunning pianism the set has the added bonus of the superb booklet notes by Reyes, which not only explore Foster’s life, character, and career but also details his musical and pianistic approach, with some jaw-dropping insights as to the technical means by which Foster created some of his extraordinary effects at the keyboard.

Here is the promo video that I produced for the Marston release, set to Foster’s exquisite account of Moszkowski’s Guitarre Op.45 No.2 from a concert performance of June 30, 1968.

I regularly explore in my postings how not all great pianists have great careers, and that many who had careers of note are not well remembered after they die, and unfortunately Foster seems to fit into both categories. He died of myeloid metaplasia (a bone marrow condition) at the age of 59, having made only a few commercial records that do not fully reveal his genius. He performed and toured widely, playing with major musicians and considered a peer by other great American pianists such as Jorge Bolet and Abbey Simon, but is the least remembered amongst this trio of pianists who had studied with David Saperton (Godowsky’s son-in-law). It is remarkable that the youngest pianist to be admitted full-time to the Curtis Institute and the winner of the first ever Leventritt Competition (the prize that would launch the careers of Van Cliburn, John Browning, and Gary Graffman) should fade into obscurity. Fortunately, the current unparalleled access to recorded performances by this exceptional musician can posthumously remedy this situation so that Sidney Foster can rightly be remembered as one of the most astounding American pianists of the 20th century, and one of the greatest in the international pantheon.

I regularly explore in my postings how not all great pianists have great careers, and that many who had careers of note are not well remembered after they die, and unfortunately Foster seems to fit into both categories. He died of myeloid metaplasia (a bone marrow condition) at the age of 59, having made only a few commercial records that do not fully reveal his genius. He performed and toured widely, playing with major musicians and considered a peer by other great American pianists such as Jorge Bolet and Abbey Simon, but is the least remembered amongst this trio of pianists who had studied with David Saperton (Godowsky’s son-in-law). It is remarkable that the youngest pianist to be admitted full-time to the Curtis Institute and the winner of the first ever Leventritt Competition (the prize that would launch the careers of Van Cliburn, John Browning, and Gary Graffman) should fade into obscurity. Fortunately, the current unparalleled access to recorded performances by this exceptional musician can posthumously remedy this situation so that Sidney Foster can rightly be remembered as one of the most astounding American pianists of the 20th century, and one of the greatest in the international pantheon.

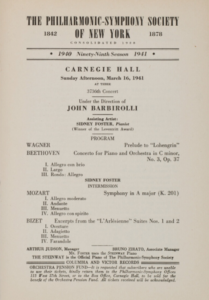

Born Sidney Finkelstein in Florence, South Carolina on May 23, 1917, he was four years old when his musical inclinations became clear. He auditioned for Josef Hofmann at age 10 and then became the youngest pupil to be enrolled full-time at the Curtis Institute of Music (Ruth Slenczynska was younger, but she was not a full-time student with a full course load like Sidney). Foster trained with the legendary Isabelle Vengerova and then for several years with David Saperton before winning the 1938 MacDowell Competition. This was followed by the 1940 Leventritt prize, which afforded him a debut performance with the New York Philharmonic under Barbirolli of Beethoven’s Third Concerto (with his own cadenza in the first movement). The enthusiastic New York Times critic Noel Strauss reported that Foster ‘proved himself a richly gifted performer’ as he ‘gave the concerto a reading in the grand manner.’

Foster’s career was launched, and with regular performances at Carnegie Hall and with major American orchestras and conductors, his playing was very well received. His appearance as one of ten international pianists on the Ed Sullivan show on October 18, 1953 is indicative of the esteem in which he was held at the time and the envisioned trajectory of his career. In this remarkable footage – alas, the only known filmed performance of Foster – we can see him (starting around the 2:25 mark) playing Chopin’s Polonaise in A Major, Op.40 No.1 simultaneously with Ethel Bartlett, Alexander Brailowsky, Gaby Casadesus, Eugene List, Moura Lympany, Guiomar Novaes, Rae Robertson, and Beveridge Webster, with the great Rudolph Ganz as conductor (though he sits down and joins in the fun at one point) – an event that was a precursor to a Steinway Centenary celebration the following night that would feature 34 pianists (Foster among them).

His playing was also recognized beyond the confines of his native country: Foster played throughout Europe, Israel, and Japan, and when the Soviet Union began to open up in the 1960s, he was among the first American artists to play there, in a tour consisting of some 22 concerts in 30 days. How that tour came about is fascinating: Yakov Fliere traveled to New York in October 1963 to make his New York debut and after attending Foster’s Carnegie Hall recital a few days after his own concerts, the Russian pianist and his own impresario were so impressed that they started negotiations to have Foster visit in the 1964-65 season.

However, health challenges would begin hinder his career: he had suffered a heart attack at 39 (in the late 1950s) and by 1962 he was diagnosed with the disease that would take him from us 15 years later. The self-effacing musician was not one to seek the limelight in any case, and his attention would become increasingly focused on teaching. After a few years at Florida State University, Foster was a beloved teacher at Indiana University for nearly a quarter century, from 1952 until his death on February 7, 1977 at the tragically young age of 59. He continued to play while tenured there, his 1970 Carnegie Hall recital rapturously reviewed by eminent pianophile Harold C Schonberg, who called it an ‘exhilarating experience,’ referencing Foster’s ‘singing tone, an ability to take liberties in a phrase without distorting the line, and a steady rhythmic momentum… He makes music in an alert and exciting fashion.’

However, health challenges would begin hinder his career: he had suffered a heart attack at 39 (in the late 1950s) and by 1962 he was diagnosed with the disease that would take him from us 15 years later. The self-effacing musician was not one to seek the limelight in any case, and his attention would become increasingly focused on teaching. After a few years at Florida State University, Foster was a beloved teacher at Indiana University for nearly a quarter century, from 1952 until his death on February 7, 1977 at the tragically young age of 59. He continued to play while tenured there, his 1970 Carnegie Hall recital rapturously reviewed by eminent pianophile Harold C Schonberg, who called it an ‘exhilarating experience,’ referencing Foster’s ‘singing tone, an ability to take liberties in a phrase without distorting the line, and a steady rhythmic momentum… He makes music in an alert and exciting fashion.’

He played less widely as his condition deteriorated, though he would continue to devote himself tirelessly to his students; Reyes had been unaware of the seriousness of his condition until the last year of Foster’s life, as he did not draw attention to himself. As insightful and inspired as Foster was in his teaching, his modesty prevailed there too: he asked Jorge Bolet to coach Reyes in Prokofiev’s Second Concerto as he knew the work better than him (having made its first recording), something the equally modest and congenial Bolet – also teaching at Indiana – was more than willing to do. The standards he held for himself as a teacher were as high as they were with his playing, and he was as lionized by his students and colleagues as he was by audiences and critics for his concerts. His students were an extension of his family: to ensure that Reyes would be able to afford studying in the US from his native Uruguay, he had his pupil stay at his own home, and he hosted an annual Thanksgiving dinner for his students who were unable to travel to see their own families.

Foster’s Recorded Legacy

As a pianist who was aware of the ephemeral nature of musical performance, Foster was not particularly enthused by recordings, leaving behind only a disc of two Mozart Concertos in addition to the complete Clementi Sonatas, but these pale in comparison to the pianism of his live performances. Fortunately he played regularly at Indiana University, where a single microphone hanging in the auditorium preserved recital performances that now form the bulk of his discography. There are a few live concerto recordings from New York, Tokyo, Salt Lake City, and Boston – Beethoven Third, Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Bartok Third – though not nearly as much as an artist of his stature warrants, and one hopes that more will be located. Two discs of recital recordings were issued in IPAM’s 1993 set ‘Ovation to Sidney Foster’ before Marston’s glorious 7-disc set of solo and concerto performances was released in 2018, and both of these sets reveal in every moment pianism of the highest order. Other performances not released in these volumes can be found on this YouTube channel.

As a pianist who was aware of the ephemeral nature of musical performance, Foster was not particularly enthused by recordings, leaving behind only a disc of two Mozart Concertos in addition to the complete Clementi Sonatas, but these pale in comparison to the pianism of his live performances. Fortunately he played regularly at Indiana University, where a single microphone hanging in the auditorium preserved recital performances that now form the bulk of his discography. There are a few live concerto recordings from New York, Tokyo, Salt Lake City, and Boston – Beethoven Third, Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Bartok Third – though not nearly as much as an artist of his stature warrants, and one hopes that more will be located. Two discs of recital recordings were issued in IPAM’s 1993 set ‘Ovation to Sidney Foster’ before Marston’s glorious 7-disc set of solo and concerto performances was released in 2018, and both of these sets reveal in every moment pianism of the highest order. Other performances not released in these volumes can be found on this YouTube channel.

Foster was a virtuoso who played on a wider landscape than how the term is generally used, as his mastery of the piano was not just in the technical sense of having a total command of precision that allowed for thrilling performances; rather, his playing was fuelled by an intelligence and understanding of the music and pianistic technique that went beyond the purely physical requirements of a performance. With an inner compass unwavering in its quest for truthful interpretation, his thorough mastery of tone production, articulation, projection, and all other elements required for an insightful interpretation were fully at the service of the music. There is a multidimensionality to his playing that one can glean from these recordings, though the effect in person would clearly be much more impactful – likely one of the reasons that Foster would not be particularly enamoured with the mechanical process of producing recordings in a studio.

His repertoire spanned from Bach to Prokofiev, and in each performance we hear the same intelligence and clarity of tone serving the musical content while clarifying the structure of the work, in a symbiotic fashion. His deftness of articulation, transparency of texture, beautiful sonority, and steady rhythm are all in evidence in this majestic March 29, 1955 performance of the Bach-Liszt Fantasia and Fugue in G Minor.

As often as one might have heard Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata, there is a freshness and vitality in Foster’s approach that makes it sound new without any contrived attempt at originality being externally imposed on it. Here is the first movement from a June 30, 1968 concert performance, where Foster plays with a phenomenal sense of architecture, articulating with tremendous clarity and phasing cohesively without ever sounding boxy, while also exhibiting boundless passion, impeccable timing, and impressive tonal and dynamic control.

In virtuosic repertoire, Foster’s musicality is still evident: this staggering 1965 concert performance of Mendelssohn’s Etude in F Major Op.104b No.2 features impressive dexterity and evenness of articulation, astoundingly clear and consistent voicing, and marvellously polished tone throughout. What striking layering of the primarily melodic content in relation to the dazzling fingerwork!

For all his technical prowess, Foster’s proficiency at the keyboard was wholly at the service of the music, and in works rich in emotional content his interpretations were probing and revealing. This April 27, 1952 performance of Chopin’s Fantasy in F Minor Op.49 features a long burnished melodic line that is mindfully shaped with articulation – not only fluid or only detached, but a subtle combination that mirrors the variety and shaping of human speech. There is gorgeous singing tone throughout, and particularly impressive is a transparent bass sound that travels through all registers without obscuring any of the other lines, an effect that is one of the hallmarks of his playing and which stands him apart from many of his better-known colleagues.

The refinement in Foster’s playing was such that on first listen one might easily overlook the absolute mastery on display. In this 1968 account of Finnish composer Selim Palmgren’s ‘May Night’, his luminous tone and seamlessness of phrasing are evident and admirable; however, most miraculous is the skillful balance between voices, a chime-like effect being produced by the flawless weighting of chords, impeccably poised so that the intervals create just the right tension. That he could achieve this while playing with such fluid legato, clarity of the primary line, and luminous tone is absolutely jaw-dropping.

Foster was a skilled chamber player as well, and given that the recordings released by IPAM and Marston consist entirely of solo and concerto performances, it seems appropriate to share one of the few chamber music performances that have been uploaded to YouTube: a truly wonderful 1958 account of Schubert’s Trout Quintet with double bassist Murray Grodner and members of the Berkshire Quartet. This magnificent performance of Schubert’s masterpiece captures all the qualities of Foster’s superlative pianism: a glistening sonority, vibrant rhythm, exquisite clarity of texture, magical pedal effects, and a huge array of dynamic and tonal shadings. And what wonderful ensemble with his colleagues – truly seamless music-making!

In contemporary music, Foster achieves what modern composers themselves aimed to do but which is so often not accomplished by most pianists: playing with consistent beauty of tone without banging when there is harmonic dissonance. This October 2, 1961 performance of some Prokofiev Visions Fugitives (Numbers 1, 3, 10, 11, 14, 15, 8, and 18) is as mindfully phrased, beautifully nuanced, and flawlessly characterized as Foster’s readings of works by any other composer. His timing, attentive use of varied articulation, and rich dynamic and tonal palette serve to individualize to perfection each of these works.

Another masterful performance of 20th century repertoire is this March 5, 1959 reading of Bartok’s Suite Op.14, which clarifies this remarkable work with his phenomenal transparency, gorgeous tonal colours, deft articulation, and rhythmic vitality – a terrifically exciting account that reveals the work’s incredible depth and richness of emotional content.

To close this tribute to this superb artist, a 1959 performance of Albeniz’s Evocación from Iberia that captures Foster’s splendid tonal colours, magnificently sculpted phrasing (notice how the ornamentation is incorporated in the line), magical pedal effects, phenomenal dynamic control (the pianissimos are breathtaking), and immaculate timing. As with all of these performances, every phrase – every note – is a sign of absolute musical and pianistic mastery. Long may we continue to hear and appreciate Sidney Foster’s artistry!