Alfred Cortot had a long career with the gramophone, having produced a vast amount of solo, chamber, and concerto recordings over the course of four decades (with some overlooked discs accompanying soprano Félia Litvinne predating the first of those by more than 15 years). However, in his many hours of recorded performances, Cortot did not produce any commercially issued discs of solo or concerted works of Beethoven, despite these being a major part of his repertoire for decades.

He very nearly did: on April 6, 1925 at the Camden Studios in New Jersey, whilst making some of his earliest electrical discs, Cortot recorded a complete Moonlight Sonata – as well as Ondine from Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit and the Ritual Fire Dance by Manuel de Falla. Unfortunately, none of the takes from that session have survived and he appears not to have made another attempt at the Beethoven in the 78rpm era.

He did, however, record and release some chamber music by Beethoven in the 1920s, such as his legendary 1928 traversal of the Archduke Trio Op.97 with Jacques Thibaud on violin and Pablo Casals on cello:

Cortot also performed with each of these musicians separately, having recorded a wonderful account of Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata with Thibaud in 1929 – here’s the first movement, played with great robustness on the part of both violinist and pianist:

As it turns out, Cortot’s last public appearance found him performing Beethoven with Casals: after a long estrangement, the two legendary musicians finally played on stage again in a reading of Beethoven’s Cello Sonata Op.69 and the Magic Flute Variations. Cortot was not in top form at the time, suffering from poor eyesight and dexterity issues, though he was more at ease in the Variations than in the Sonata. Here is that performance, in which we can hear his gorgeous sonority, deft articulation, and marvellous phrasing:

Why Cortot did not record solo works of Beethoven after that first attempt in 1925 is not entirely clear, though it seems very likely that the expense of the recording process and the records themselves did not allow for multiple artists recording the same works. The French pianist’s fame as a Chopin interpreter resulted in him focusing primarily on that composer’s output, just like Schnabel with Beethoven and Fischer with Bach; similarly, the latter played Chopin into the 1950s but never recorded a note of his music. The industry was not yet committed to preserving multiple accounts of the same works by several performers on the same label, and so many of these artists recorded according to whatever their ‘niche’ was seen to be: Bach for Fischer, Beethoven for Schnabel, and Chopin for Cortot, with the former two occasionally venturing into each others’ “territories” but not the latter’s.

Cortot would eventually record the complete Beethoven Sonatas in the late 1950s when he was over 80 years old, in two formats: as uninterrupted performances and as lecture-demonstrations in which he played excerpts after speaking about the work (in French as eloquent as his pianism). However, his technique had deteriorated so much by this point that his playing was such a pale shadow of its previous glory and as a result these performances remained unreleased for decades.

Only a few complete Sonatas and lecture presentations were released in 2012 in the 40-disc Anniversary Edition produced by EMI France: producer Rémi Jacobs chose to include only a limited number as even with moments of great beauty, Cortot’s playing is quite unstable in more technically taxing passages and well below the standard of the bulk of his sanctioned recordings (he assured me that those that remained unreleased made for uncomfortable listening). There are many details to enjoy in the recordings that were made available, though it is often clear that Cortot is well past his prime.

Here, at last, we can hear the aged Cortot playing the glorious Moonlight, albeit in lecture-demonstration mode some three decades after that early attempt at recording the work. While this is not quite what we would have heard had that first account been preserved, there are indeed some marvellous moments in this document, the first movement being particularly exquisite:

There are other examples of Cortot playing Beethoven in an actual classroom situation just a few years earlier which may give a better idea of his brilliance in this repertoire. Murray Perahia compiled a fantastic 3-CD set of recordings of Cortot teaching while demonstrating at the piano, and the Beethoven examples are utterly remarkable, far better than what we hear in the late studio accounts like that above. This demonstration of Op.110 is so illuminating that it makes all the more lamentable the absence of a complete recording of Cortot in the work while in his prime:

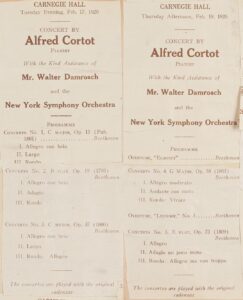

When it comes to Beethoven’s concertos, it is truly unfortunate and rather astonishing that Cortot recorded none of them as they were all in his repertoire for a long time. In fact, Cortot recorded surprisingly little for piano and orchestra: despite a broad repertoire that included the complete Beethoven and Saint-Saëns Concertos, and Rachmaninoff’s Third, he only set down five works for piano and orchestra (the Schumann, Chopin F Minor, Saint-Saëns 4th, Ravel Left-Hand, and Franck Symphonic Variations – the Franck and Schumann more than once). In fact, his New York debut in February 1920 consisted of performances of the 5 Beethoven Concertos in two concerts with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Walter Damrosch (programmes visible on the right).

However, we are fortunate that relatively recently, one Beethoven Concerto recording of Cortot was found: an April 13, 1947 concert performance of the Piano Concerto No.1 in C Major Op.15 in which Cortot is accompanied by Victor Desarzens and the Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne. This broadcast was discovered by researcher Frederic Gaussin (kudos and thanks to him!) and is thus far the only concerto broadcast of Cortot playing a concerto that he had not already recorded in the studio. The performance was issued only once, on the Tahra label in 2007. Other broadcasts of Cortot made a few years later with the same chamber orchestra, playing the Chopin F Minor and Schumann Concertos, were not released as they do not feature Cortot’s playing in a very positive light.

This appearance took place not long after the pianist moved to Switzerland from France, after having been banned from public performance for a year due to his association with the Vichy regime and his subsequent poor reception at his return performances in Paris – he had been booked to play the Schumann Concerto and the orchestra walked off stage when Cortot came on, and he played a solo concert instead.

Although Cortot was not at the peak of his powers at the time (he was approaching the age of 70), his precision had not waned to the extent that it would over the coming years, as referenced above. Despite just a few inaccuracies not significantly worse than some of what is heard in his discs from the previous decade (and one lapse in the last movement), there is much to enjoy in this remarkable performance. Cortot’s distinctive singing sonority, magical pedal effects, soaring phrasing, and evocative timing are all in plain abundance.

The interplay between left and right hands is as magnificent in this reading as it is in the pianist’s celebrated Chopin and Schumann recordings, and his expansive rubato and sumptuous nuancing are wonderful complements to his robust accenting. There are also some interesting adjustments where he plays in a different register and adds some robust bass octaves at the beginning of orchestral tuttis. What is unclear is why he did not play the first movement cadenza – the New York programmes indicate that the original cadenzas were played in the concertos, so it seems odd that he would have left it out in this performance. Nevertheless, a stunning performance and fascinating historical document of one of the most important pianists of the 20th century.

In my early years of collecting a mere 30-35 years ago, the thought of hearing Alfred Cortot play Beethoven sonatas and concertos would have seemed impossible, and yet now we have so many precious excerpts and the entire First Concerto readily available. May these incredible documents be appreciated for the musical wealth that they offer, and hopefully other such treasures will be made available in the future.

Comments: 3

How wonderful that we should have the C major concerto! Thank you for sharing this as well as the other recordings, and thank you also for your insightful essay.

Excellent! Never knew he recorded the complete Sonatas. Now I must have that, at least the Hammerklavier

Though you have previously expressed your disinclination to regard piano rolls as “actual” recordings, Cortot made what I believe to be definitive recording of Beethoven’s Op. 109 for Duo-Art. It makes one yearn for more. He was also contracted to record the Op. 1 06 & Op. 110 Sonatas for Duo-Art, but – alas -only the 2nd movement of the Hammerklavier was ever released – and only in the UK.