Every composition recorded has its first recording, and it can be fascinating to explore early accounts of some of the repertoire that has since become mainstream, particularly when the music was set down when it was relatively new. The two key performances that will be part of this feature are among the most fascinating that I have heard in this regard: the world premiere recordings of Scriabin’s 9th and 10th Piano Sonatas.

The first ever recorded accounts of the Russian composer-pianist’s final two Sonatas were set down by Alexander Sienkiewicz (1903-1982). Not yet 23 years old, the Polish pianist was tasked with recording the works at Deutsche Grammophon’s Polydor studios in Berlin in January 1926 but the discs had extremely limited distribution: the recordings had been commissioned by the Japanese record club Dainippon Meikyoku Rekodo Seisaku Hampu Kwai (大日本 名曲 レコード制作 頒布會 – the last character would be 会 in modern script and pronounced Kai; in English the rough translation is the Great Japan Masterpiece Record Production Distribution Society). This organization was founded in 1925 by novelist and music critic Nomura Kodo and would commission a number of world premiere recordings. Only 400 copies of the three-record 78rpm disc set were pressed and these were sold to members for the tidy sum of 15 yen – about $400 US today (although 15 yen in today’s Japanese currency is about 15 cents).

This 3-disc Scriabin set saw the two sonatas spread across the six 78rpm disc sides of about 4 minutes each, 3 sides for each work: 1-A, 1-B, 2-A for Sonata No.9 and 2-B, 3-A, and 3-B for Sonata No.10. They were recorded on a Blüthner piano and although it sounds like this recording was made using the acoustical process that amplified musicians using cone-shaped horns, it was in fact a new system licensed from US Brunswick called ‘Light-Ray’ that was used; it was not successful and was out of use by the following year, but the regrettable result is that these recordings have more faded sound and less fidelity than if the newer standard of microphone amplification had been used. Nevertheless, Sienkiewicz’s performances here are absolutely breathtaking. It boggles the mind to consider that both of these Scriabin Sonatas – his final works in this form – were composed in 1913 (the same year the Polydor label was founded), meaning they were barely 13 years when this January 1926 recording was made about 97 years ago.

How and why Sienkiewicz was chosen to record these works is not known, but at the young age of 22 he plays with astonishing maturity, capturing to perfection the otherworldly, mystical atmosphere of these avant-garde compositions. Far from merely playing the notes and producing ‘effects’, he plays with incredible dimensionality: his tonal colours (appreciable despite the primitive sound), skillful use of pedal, fluid timing, and transparent voicing all work together beautifully in highlighting the evocative nature of the music.

Here first is the Sonata No.9 Op.68, the “Black Mass” Sonata:

And here is the Sonata No.10 Op.70:

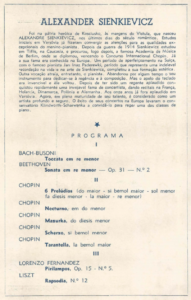

There is very little information available online about the pianist, or other recordings. Aleksander Witold Sienkiewicz was born June 16, 1903 in Kazimierz on the Vistula and he was not just a pianist but also a composer and conductor. He was related to the esteemed writer Henryk Sienkiewicz, who was an uncle or great-uncle. He had studied with Józef Turczyński, Juliusz Wertheim, and Egon Petri – with the latter most likely in Berlin, where he himself became a teacher at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory. He had earned an honourable mention in the 1932 International Chopin Piano Competition, and also had a trio with his brothers Henryk (a violinist) and Edward (a cellist) called the Orkiestrę Braci Dorian – the Dorian Brothers Orchestra. Why he used the name Dorian at times instead of Sienkiewicz in his native country is unclear but all of the 1920s record labels and concert programs from the 1940s onward use his birth name and not Dorian.

There is very little information available online about the pianist, or other recordings. Aleksander Witold Sienkiewicz was born June 16, 1903 in Kazimierz on the Vistula and he was not just a pianist but also a composer and conductor. He was related to the esteemed writer Henryk Sienkiewicz, who was an uncle or great-uncle. He had studied with Józef Turczyński, Juliusz Wertheim, and Egon Petri – with the latter most likely in Berlin, where he himself became a teacher at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory. He had earned an honourable mention in the 1932 International Chopin Piano Competition, and also had a trio with his brothers Henryk (a violinist) and Edward (a cellist) called the Orkiestrę Braci Dorian – the Dorian Brothers Orchestra. Why he used the name Dorian at times instead of Sienkiewicz in his native country is unclear but all of the 1920s record labels and concert programs from the 1940s onward use his birth name and not Dorian.

It appears that Sienkiewicz also worked with Paderewski in Switzerland – his famous relative was friends with him prior to his own death in 1916 – and Alexander would transform his technique under his legendary compatriot’s guidance and develop a friendly relationship with him. He ended up marrying one of Paderewski’s nieces and left Europe during the War, spending about five years in Buenos Aires as a conductor before moving in 1947 to Rio de Janeiro, where he had played and conducted as early as 1942 (including conducting Tchaikovsky’s 1st Concerto with Maryla Jonas at the piano), and he would spend the remaining 35 years of his life living there.

Very little information about Sienkiewicz is available online and some of the details being shared here come from the only student of his that I could track down, Maria Saboya, a Brazilian musician now living in France. Saboya trained with him for three years in Rio starting in 1952. She had been studying at the Superior School of Music in Rio but at the age of 15 felt she didn’t have the technique that she required. One day at a shop she happened to see a small poster for Sienkiewicz’s own school so she went to see him and immediately found him to be exactly the teacher she needed – and Sienkiewicz believed that Saboya was the student he needed, as he saw tremendous promise in her and hoped to develop both of their careers simultaneously.

Very little information about Sienkiewicz is available online and some of the details being shared here come from the only student of his that I could track down, Maria Saboya, a Brazilian musician now living in France. Saboya trained with him for three years in Rio starting in 1952. She had been studying at the Superior School of Music in Rio but at the age of 15 felt she didn’t have the technique that she required. One day at a shop she happened to see a small poster for Sienkiewicz’s own school so she went to see him and immediately found him to be exactly the teacher she needed – and Sienkiewicz believed that Saboya was the student he needed, as he saw tremendous promise in her and hoped to develop both of their careers simultaneously.

Lessons were long – 2 or 3 hours – and not inexpensive, but Saboya found him to be exceedingly caring, attentive, and brilliant. He prepared her for competitions and she developed great facility but like many in her culture, she married young and then didn’t pursue a performing career, much to Sienkiewicz’s disappointment. Years later as she returned to the piano would study with other respected pianists, such as Evgeni Malinin and Nicole Henriot-Schweitzer, but some seven decades after she first met Sienkiewicz she still considers him to have been her best and most influential teacher, with their work together being the foundation of her own technique and teaching, about which she has written a book (still unpublished – more about her teaching at this link). “His knowledge of piano technique was really fantastic and extremely rich. And he gave all he knew during his lessons with extreme generosity.”

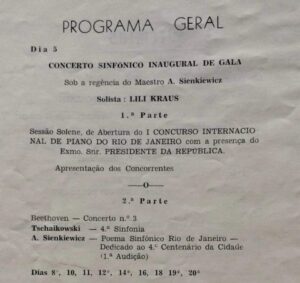

It appears that disappointment was a major theme in Sienkiewicz’s life as he was quite unrecognized for his capabilities in Brazil. Saboya never heard him play a recital while she knew him but she did hear him as a conductor in a work he had composed. Other programmes located in Brazil indicate that he conducted no less than Lili Kraus in Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.3 at a gala concert that included a performance of his own orchestral work, the Poema Sinfonico Rio de Janeiro, and he had played his own Piano Concerto Op.5 in Rio in 1942 while he was still based in Buenos Aires. He was president of the jury of the 2nd and 4th International Piano Competition of Rio de Janeiro (in 1959 and 1965 respectively) so it’s not like he was completely unknown; and Alexandre Dias of the Brazilian Piano Institute found a newspaper clipping indicating that Shostakovich had asked Sienkiewicz to be on the jury of the 1966 Tchaikovsky Competition, but for whatever reason it appears that he did not go. However, the pianist’s wife worked as a cleaning lady while he struggled to pay the rent for his small apartment because he had so few students, mostly older ladies who were never at the level of a concert artist (hence his dismay at the talented young Saboya not pursuing her career). Despite his lack of success in Rio, he never moved elsewhere and he died there on January 23, 1982 at the age of 78.

It appears that disappointment was a major theme in Sienkiewicz’s life as he was quite unrecognized for his capabilities in Brazil. Saboya never heard him play a recital while she knew him but she did hear him as a conductor in a work he had composed. Other programmes located in Brazil indicate that he conducted no less than Lili Kraus in Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.3 at a gala concert that included a performance of his own orchestral work, the Poema Sinfonico Rio de Janeiro, and he had played his own Piano Concerto Op.5 in Rio in 1942 while he was still based in Buenos Aires. He was president of the jury of the 2nd and 4th International Piano Competition of Rio de Janeiro (in 1959 and 1965 respectively) so it’s not like he was completely unknown; and Alexandre Dias of the Brazilian Piano Institute found a newspaper clipping indicating that Shostakovich had asked Sienkiewicz to be on the jury of the 1966 Tchaikovsky Competition, but for whatever reason it appears that he did not go. However, the pianist’s wife worked as a cleaning lady while he struggled to pay the rent for his small apartment because he had so few students, mostly older ladies who were never at the level of a concert artist (hence his dismay at the talented young Saboya not pursuing her career). Despite his lack of success in Rio, he never moved elsewhere and he died there on January 23, 1982 at the age of 78.

Sienkiewicz appears to have made a few other recordings in the 1920s, for Germany’s domestic Grammophon label and their export Polydor label, as well as for Krystaly and Imperial. The only one of these currently online is the electrical (microphone-amplified) recording from 1927 of the Gounod-Liszt Faust Waltz which naturally captures his tone and nuancing with great fidelity. While the image on this YouTube upload refers to Sienkiewicz having used the name Aleksander Dorian, all of the record labels I’ve seen use his birth name of Alexander Sienkiewicz. I have not yet managed to locate the other records – there’s a Liszt 12th Hungarian Rhapsody and Chopin A-Flat Polonaise, at the very least (recorded, I am told, ca. 1933) – but as this Faust Waltz recording reveals in better sound than his Scriabin discs, he had an incredibly full-bodied sonority (Saboya indicated that he had very thick fingers), fluid phrasing, refined nuancing, and tremendous rhythmic vivaciousness.

Sienkiewicz appears to have made a few other recordings in the 1920s, for Germany’s domestic Grammophon label and their export Polydor label, as well as for Krystaly and Imperial. The only one of these currently online is the electrical (microphone-amplified) recording from 1927 of the Gounod-Liszt Faust Waltz which naturally captures his tone and nuancing with great fidelity. While the image on this YouTube upload refers to Sienkiewicz having used the name Aleksander Dorian, all of the record labels I’ve seen use his birth name of Alexander Sienkiewicz. I have not yet managed to locate the other records – there’s a Liszt 12th Hungarian Rhapsody and Chopin A-Flat Polonaise, at the very least (recorded, I am told, ca. 1933) – but as this Faust Waltz recording reveals in better sound than his Scriabin discs, he had an incredibly full-bodied sonority (Saboya indicated that he had very thick fingers), fluid phrasing, refined nuancing, and tremendous rhythmic vivaciousness.

It is hoped that the rest of this artist’s modest studio output will be located and professionally transferred and that some concert or private recordings could also be located. Clearly an artist of tremendous capabilities, one to remember and explore – not least for his pioneering Scriabin recordings of 1926.

Many thanks to Maria Saboya, Alexandre Dias, Marek Przybyszewski, JiHoon Suk, and Jon M. Samuels for the invaluable details they provided for this feature

Comments: 3

As usual, great job of researching this pianist.

Thank you, James – he really caught my attention and interest. Hopefully we can find out yet more about him, and some more recordings.

Thank you so much for this historical contribution and insight into an era nearly a century past. It is a pity the world forgot his 150th anniversary this past year as we now focus on rachmaninoff’s which is already being acknowledged throughout programming for a number of factors not withstanding covid… As a Scriabin specialist who has performed the late sonatas in concert and on broadcast on wfmt here in Chicago and who has studied with the late Russian pianist Dimitri paperno himself a student of Alexander Goldenveiser, himself a personal colleague and exponent of the later works in the Soviet Union at a time when this music was eclipsed for a generation… I find this playing to be pure refreshing straightforward honest fluid with beautiful tone irrespective of the inferior fidelity recording standards at the time… You are to be commended for a wonderful find and I can’t help feeling that this pianist would have enjoyed far greater recognition if he would have returned to the European cultural scene during peaceful times… I say this having studied and danced tango for 7 years and two trips to Buenos Aires and Mexico experiencing the great composers of Latin America and the incredible tango music that initially drew me to this art form. Covid wiped out tango temporarily but drew me back to Scriabin who was the greatest poet of the piano since Chopin in my humble opinion.