About The Piano Files

I loved classical music as a child. I clearly remember my enthusiasm when hearing certain classics, like Brahms’ Fourth or Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphonies. For a while, however, my love for this form of music waned, despite my study of the piano. It was my piano teacher in Montreal who woke me up to the brilliance of another dimension to music and changed the course of my life.

At the age of 15 or so, I bought a record of the Beethoven 32 Variations (by Bruno Leonardo Gelber, for those who want to know) because I was learning the work, and I wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about the performance. My teacher commented on how thin the record was and took me to her hallway closet to show me her collection of 78s. We had a good laugh as we looked at how thick the old records were. She was raving about the wonderful performances, wishing that she could find the 78s she’d had of Horowitz playing the 32 Variations, when one of the sets she pulled out caught my attention. “Look,” she said, “Rachmaninoff plays Rachmaninoff.”

Now, I had heard of Rachmaninoff before, although I didn’t know his music very well (philistine that I was!), but what struck me was the concept of a composer playing his own music. I was very disappointed by Gelber’s performance and was hoping for something more authoritative. If only we could hear composers play their own works… And here was a set of Rachmaninoff playing his own compositions! I realized that I had no idea about the history of recording: when were the first records made? What composers had recorded their own works?

My parents’ old record player played 78s, so I asked if I could borrow the records and took them home and listened with fascination. Sure, there were scratches, but the sound was quite clear and it was, of course, an authoritative performance. I began to think about how recording must have been much more complicated in the past, given the more restrictive format of recording on 78s (no tape splicing meant that performances were recorded in ‘live’ 4-minute segments, and sequenced from one record to the next). It seemed natural that as a result, only the best artists would be able to make recordings. I wondered if perhaps due to the challenging nature of recording back then the quality of musicians was higher than those featured in today’s recordings.

And thus began a quest to learn more about the musicians of the past and how they performed. Harold C Schonberg’s classic tome ‘The Great Pianists’ served as an important reference, with his enthusiastic descriptions of many great pianists from the early years of the keyboard through to the dawn of recording and the present day. I had never heard of Cortot, Hofmann, Friedman, Bauer, and so many others, and with his suggested pianists in mind, I scoured second-hand shops looking for records of these artists. Over the coming weeks, months, and years, I found many such records, and their liner notes and other reference materials helped me to learn more about the lives and artistry of many fascinating musicians.

As I listened to these old records, I postulated that with less of a time lag between the time of composition of the great repertoire and the time that recordings were made, performers in the 20s, 30s, and 40s might have been doing more justice to the composers. Of course it had not yet struck me that there were still mannerisms of the time that had to be taken into account – Beethoven might have been played with a 19th-century approach that did not necessarily correspond to the style in vogue at the time he composed – yet for a number of composers, my theory made sense. I was particularly struck by the difference between Rachmaninoff’s own performances and those of pianists 50 years later, even 20 years later. If a significant change had taken place in so short a period of time, what damage were we inflicting on the likes of Bach and Beethoven? Since it was possible to hear students of the great Liszt performing his works, there was clearly lots to be learned.

However, I felt then (as I do now) that the antiseptic attempt at ‘original instruments’ and ‘authentic performance practice’ was missing the point. Following the text with a microscope gives one a better view of the map but not the territory, and clearly the composers would have wanted to explore instruments with greater sonic and interpretative capabilities than those that were available to them. I believe, as the pianist Dinu Lipatti phrased it, that music lives beyond the means of interpretation used at the time of its composition – this is what renders it timeless. The instruments used were at best an approximation of the sounds that the composers heard with their inner ear.

I continue to relish the performers of the past, as well as those worthwhile talents of today who have managed to cut through the heartless industry that has overtaken the art of music. All musical interpreters worth their salt are performing the same task: expressing emotion through sound. While the modern piano industry has done untold damage, with competitions that reduce playing down to quantifiable standards such as technical accuracy without a feasible way of ‘grading’ emotional expressiveness and individuality, there are still some brilliant performers today…though some of these are not the ones most commonly heard.

This site will serve as a resource with which to shed light on the greatest pianists of the past and present. Enjoy!

The host of The Piano Files

Mark Ainley is an internationally recognized authority on the art of piano playing and historical recordings of great pianists. His clear insights provide important details about the mastery of the pianists of the past and present through his magazine articles, blog and social media pages, CD productions and liner notes, and lecture-demonstrations.

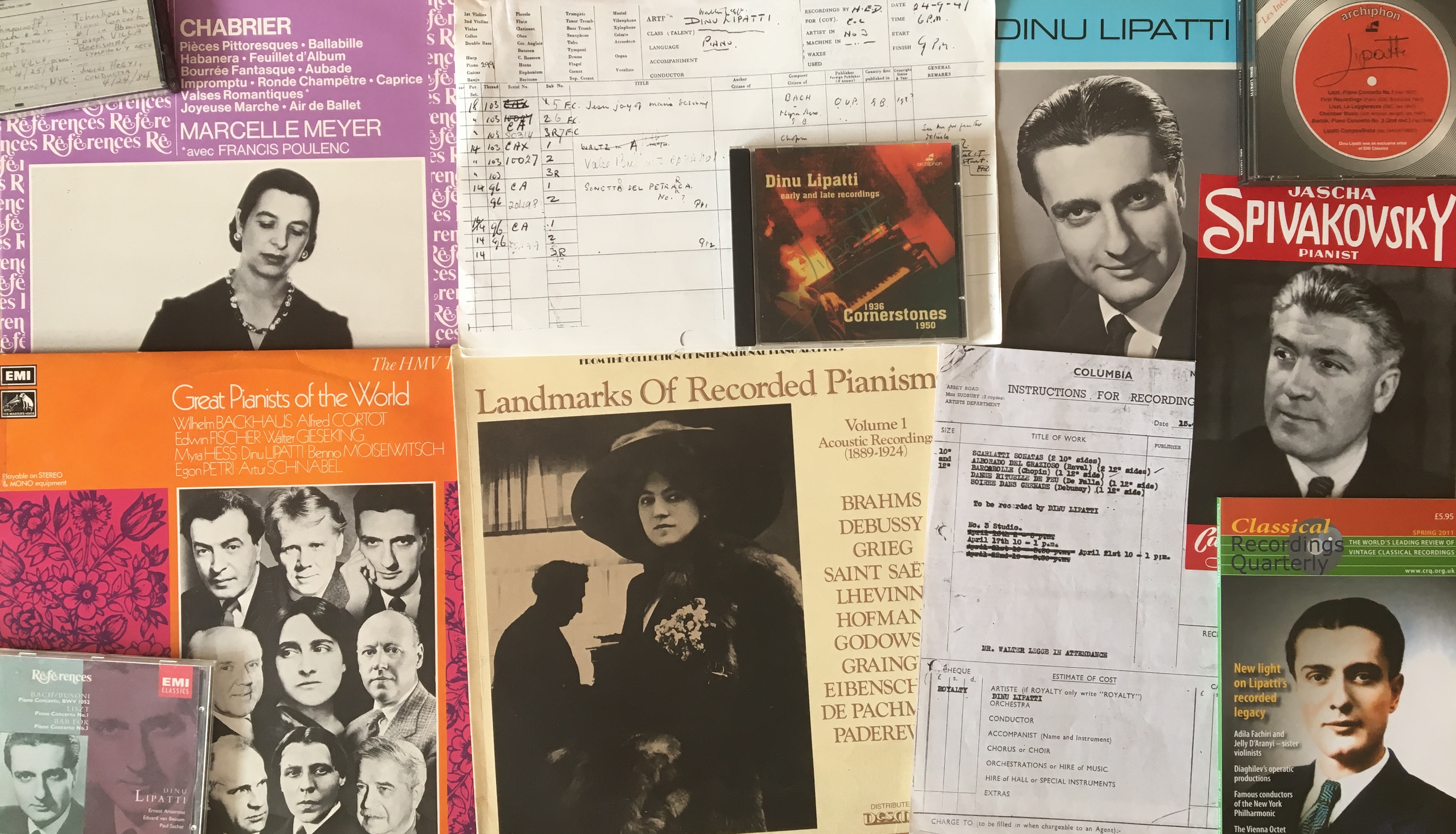

Mark’s work in the field of historical recordings began in his late teens, when his pre-university writing and research on this topic won the admiration of Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times music critic Harold Schonberg. His first CD liner notes, for VAI’s release ‘Liszt: The 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies Played by 19 Great Pianists’, were co-authored in his early 20s with International Piano Archives founding president Gregor Benko, coinciding with Mark’s pioneering work in discovering previously unpublished recordings of the legendary pianist Dinu Lipatti. His internationally acclaimed efforts led to the world premiere award-winning release of over two hours of ‘unknown’ performances by Lipatti, among them piano concertos by Liszt and Bartok.

Mark’s articles about Lipatti for International Piano Quarterly, International Piano, and Classical Record Collector magazines, as well as liner notes for the labels APR, archiphon, and Opus Kura, have debunked myths surrounding the life and art of this legendary musician, and he has received support for his work from some of the Rumanian biographers, diplomats, and producers who have worked for decades in publicizing this musician’s legacy. Mark has also written in both International Piano and Classic Record Collector magazines about the great French pianist Marcelle Meyer, the muse of Le Groupe des Six in 1920s Paris who additionally worked with Ravel, Debussy, and Stravinsky.

Mark has given lectures at the Manhattan School of Music in New York, the Leschetitzky Society in Tokyo, and the San Francisco Conservatory, speaking about Great Historical Recordings in general and about Dinu Lipatti specifically, and was featured on WNYC radio in New York City in 1992 for the premiere broadcast of some rare Lipatti recordings. In September 2010, Mark co-chaired the panel discussion after the screening of a documentary about Dinu Lipatti at the Besancon International Music Festival, and the following month he opened the 2010 Great Romantics Festival with a presentation entitled “Schumann—The Poet of the Piano” for the bicentennial of Schumann’s birth. In 2016 the Romanian Cultural Institute in Bucharest sponsored a trip for Mark to visit Romania and lecture about Dinu Lipatti in conjunction with a new Lipatti website; Mark additionally appeared on Romanian TV and radio on this trip. He also presented at the Romanian Cultural Institute in Vienna in 2017 to mark the beginning of Lipatti’s centenary that year.

Mark’s international research has led to meetings with many musical luminaries, among them Elizabeth Schwarzkopf, Yehudi Menuhin, Hugues Cuenod, Franziska Ackermann (widow of conductor Otto Ackermann), Stephen Hough (who has referred to Mark’s blog in his own for The Telegraph), Idil Biret, the family of Marcelle Meyer, Lake Como Piano Academy director William Nabore, and renowned artist manager Jacques Leiser.

Mark has regularly written long features in International Piano magazine about a number of pianists and topics, such as the evolution of Alfred Cortot’s playing as heard through his recordings, the challenges facing young pianists as related by Jacques Leiser, an interview with British-Canadian pianist Valerie Tryon, and biographical articles about Dinu Lipatti and Marcelle Meyer. Starting in September 2023, he has a new regular column in International Piano entitled Historical Perspectives (the first one can be read here). Mark has also published an extensive 9-page article about Dinu Lipatti for Classical Recordings Quarterly, and for Clavier Companion magazine has produced an article about recording producer Walter Legge, a feature on the ‘rediscovered Romantic’ pianist Jascha Spivakovsky, and interviews with Stephen Hough and Livia Rev. Mark continues his research into the life and recordings of Dinu Lipatti and has prepared a commemorative website devoted to the artist at dinulipatti.com .

Mark has been a regular guest lecturer piano literature classes at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, BC, and he guest lectured at Manhattan School of Music in April 2017. He is available for writing projects such as CD liner notes, articles, and interviews, as well as lecture-demonstrations on a variety of piano-related topics. Amongst his repertoire:

- In The Groove: An Introduction to Historical Recordings

- Dinu Lipatti, Prince of Pianists

- Marcelle Meyer, Muse of Les Six

- The Great Romantic Pianists

- Legendary Chopin Interpreters

- ‘Live, from New York…’

- Fabulous French Pianists

- Unknown Greats

- Off The Record: Rare Unpublished Recordings

Additional topics available on request.

For booking inquiries, please write to mark@markainley.com

“Mark Ainley is one of the most knowledgeable music experts and writers on musical subjects that I have encountered.” – Jacques Leiser, former EMI producer to Richter and manager to Michelangeli

“How could you possibly know what you know at your age?” – Elizabeth Schwarzkopf

Piano Files Patrons

Many thanks to my supporters whose subscriptions on Patreon and donations by PayPal help to support the production of content on this website.

Donald Wright

Alex Forbes

Felix Buchmann

Aurelien Jolly

David Kinney

Furio and Ron Zerafa

Eric Barnhill

Dennis Malone

Yuko Suzuki

David Hull

Francis Crociata

Alberto Reyes

Eden Spivakovsky

Jeff Tam

Robert Dvorkin

Ray Edwards

Greg Dell

Rose Leiman

Alex McIntyre

James Irsay

Lidia Amorelli

Charles Timbrell

Chase Kimball

Joe Salerno

Edward Ronayne

Hendrik Slegtenhorst