Pianophile and recording historian/researcher Allan Evans passed away on June 6 at far too young an age. Evans played a particularly active role in bringing attention to the playing of the great Polish pianist Ignaz Friedman, producing the first ever comprehensive reissue of the pianist’s recordings and penning a biography of the artist. On his label Arbiter, Evans also highlighted artists who were frequently overlooked and presented performances that showed a different side to an artist’s capabilities than was generally known, in addition to exploring world music on his Arbiter World label.

Despite having had communications online since the late 90s, I only met Evans for the first time in 2018 when I visited New York. The get-together was coordinated by Artur Schnabel’s granddaughter Ann Mottier, a close friend of Evans who believed that we would get along wonderfully – and that we did. Together with our mutual friend James Irsay (whom I first met in New York in 1992 when I was invited to appear on his program on WNYC courtesy another mutual friend, Gregor Benko), we spent hours dining together and discussing many musical matters. Any differences of opinion that we had had in online conversations evaporated as our enthusiasm for our shared passion of inspired music-making drove our conversation – as can be clearly seen in photographs that Mottier snapped on the occasion.

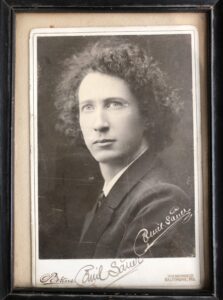

Evans and I met one more time on that trip, for a Thai dinner at a hole-in-the-wall restaurant that he adored – as with his music, Evans preferred a down-to-earth unfussy authenticity versus dressed-up, dolled-up presentations that lacked the grittiness of robust aliveness. Over the course of our dinner (at which he gave me the wonderful autographed Emil von Sauer photo shown here), I remember us discussing in particular the pianism of Ilona Eibenschütz and how the playing of those who knew Brahms ruffled the feathers of academics, about whom he uttered a line that I will always remember and use myself: ‘they want their playing embalmed, not alive.’ That incisive directness and down-to-earth clarity epitomizes Evans’ approach to and fascination with music, and all art forms, and life: real, robust, unconventional, in-the-moment.

After his passing, for one week I posted a performance daily on my Facebook page that related to his research, whether an artist he appreciated or a recording that he released on his Arbiter label or on the Pearl label prior to Arbiter’s founding. His contributions in this field were so profound that it made sense to gather them here, along with a few others, for permanent reference.

Ignaz Friedman

My tribute to Evans must begin with Friedman, the artist about whom he was the most passion and who had provided the impetus for his exploration of historical recordings. A Romantic of the highest order, Friedman had a beautiful singing sound, a rich tonal palette, and complete mastery of the pedal, while voicing creatively and phrasing with wonderful rubato fused with sensitive dynamic shadings.

Friedman’s rhythmic emphases in the mazurkas is the stuff of legend and startles the conservatory crowd, though Friedman’s having danced the mazur as a child lends his approach a certain level of authenticity that the current musical climate claims to aspire to but which they can find off-putting because it doesn’t match their picture of what Chopin playing should be like (they would do well to read of the composer’s argument with Meyerbeer over the rhythm he wanted in these works). This brings to mind that line of Evans quoted above about performances being alive as opposed to embalmed.

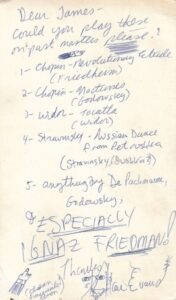

Well, this is certainly very alive playing – there is a vibrancy and vitality that are mesmerizing! And it is this recording that led to the long friendship between Evans and James Irsay: back in 1972 when Irsay had another program on WBAI, he played a 78rpm disc of Friedman playing Chopin’s A-Flat Polonaise – the first occasion that Evans heard this artist’s playing – and over their shared love of this robust pianism a deep friendship between the two was born. On the left you can see a note that Allan wrote to James soon after with requests for broadcast (though interestingly he mistakenly put Friedheim’s name instead of Friedman’s in the first number)!

I am also not suggesting everyone run out and imitate Friedman – but whenever one is ‘offended’ by a musical choice made by an artist trained in the 19th century, it is worth looking at what belief is being challenged, what stylistic preference is so strongly held, and why. It is not necessary to change one’s preferences or style of playing, but not questioning where these come from and why they are so important to you does not create space for accurate scholarship and musical study.

This truly is essential listening for any lover of great piano playing and we do indeed owe Evans tremendous gratitude for his work in bringing this artist more to the foreground.

Ignace Tiegerman

A pianist rescued from obscurity by Evans was Ignace Tiegerman, a pupil of Ignaz Friedman. Having lived in Cairo for his health and never made commercial recordings, Tiegerman evaded international recognition and was basically unknown to pianophiles until Evans released all the recordings he could find.

While Tiegerman’s character and approach are clearly quite different from Friedman’s, the amateur home and radio recordings we have demonstrate some fine pianism – unfortunately most suffer from very poor sound but this 1965 account of the Brahms Capriccio in B Minor Op.76 No.2 is clearer in fidelity than most. Tiegerman’s tone is absolutely gorgeous, with seamless legato phrasing and transparent textures helping one hear the beauty of Brahms’s writing – and what buoyancy in the accompaniment while sustaining lyricism in the melodic line. Marvellous playing!

Pietro Scarpini

An unsung pianists who fascinated Evans was Pietro Scarpini, a largely overlooked figure whose playing was both robust and intelligently crafted. While Evans did not release a great deal of the artist’s performances, the disc he did put out included this truly marvellous 1952 concert performance of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.4 with Scarpini and legendary conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler. The atmosphere features that unique combination of divine inspiration and down-to-earth directness that was so much a part of Evans’ character and musical aptitude.

Egon Petri

An incredible discovery Evans made was a truly remarkable broadcast recording of Busoni’s pupil Egon Petri playing the fourth movement of the Busoni Piano Concerto from a 1932 (!) concert, with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by the great Hans Rosbaud.

Allan recounted that he went to Melodiya’s offices in 1987: “Waited for a meeting room to be prepared (someone hurried inside with a reel of tape – not so subtle.) Met their archivist who claimed the entire 1936 broadcast existed minus the 1st movement, in a private collection. The Red Army took everything in 1945. Two years later during Perestroika the 1932 Busoni movement and most of Totentanz emerged. The 1936 performance seems to be missing unless an army officer will ‘fess up. Took a while to get them. Worth the effort.”

Worth the effort indeed. It is staggering that a 1932 broadcast should exist at all and in such amazing sound, and one shudders to think of the whole performance played this way by this great student of the composer; the 1936 Totentanz (with the opening missing) referred to above was also released by Allan on one of his Arbiter CDs and features equally stunning pianism.

Petri could at times be uninvolved and detached (more so in the recording studio than in the concert hall) but that’s far from the case here: this is absolutely thrilling playing, with the easily surmounting the technical challenges of this work despite playing at breakneck speed – what octaves, with incredible voicing and rhythmic vitality. A truly phenomenal document of tremendous historical importance!

Madeleine de Valmalète

Another artist whom Evans adored was the French pianist Madeleine de Valmalète, who had been admired as a child prodigy by Saint-Saens and Widor and by Ravel and Cortot when a developed pianist. While she performed with important conductors across Europe, she never toured the US and didn’t care for recognition, so while she lived to 100 years old she was largely overlooked. This 1928 recording of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No.11 that Evans issued on his tribute disc to the artist captures her fiery yet refined pianism marvellously well, with some truly idiomatic rhythmic adjustments in the final section.

Marius-François Gaillard

Another artist more recently championed by Evans was a French pianist who became a conductor and lived as late as 1973 – largely forgotten despite having been a major proponent of Debussy’s piano music during and soon after the composer’s lifetime: Marius-François Gaillard.

Evans was the first to reissue Gaillard’s obscure Debussy piano recordings – I don’t think they ever made it onto LP – and they are significant documents unjustly overlooked: Gaillard was the first to play Debussy’s then-complete piano works in three concerts in 1922. A review at the time stated that “Among the illustrious interpreters of this incomparable musician [Debussy], Marius-Francois Gaillard has proved to be the most truthful, the most inspired, the one whose action is most striking to an audience.”

His playing in his 1930 recording of Debussy’s ‘Pour le piano’ presented here is absolutely magnificent, with a wonderful balance of pedal and clarity, sumptuous tonal colours, a refined dynamic palette, and marvellous phrasing.

Severin Eisenberger

Evans was often in the right place at the right time, connecting with just the right person to ensure that something was preserved. The recordings of Severin Eisenberger are a prime example: the Leschetizky pupil seems to have made no recordings but Evans ensured the preservation of some, among them this superb May 14, 1938 concert of the pianist playing Chopin’s F Minor Concerto with the Cincinnati Conservatory Orchestra under Alexander von Kreisler.

He told the story of how this and other broadcasts were rescued from oblivion: “After his passing in 1945, his widow received a mysterious box by the custodian of their Manhattan apartment house: the pianist once intended to throw it away. He told the custodian that it contained records made of his radio recitals and that he was displeased with the mistakes. The custodian realized his mistake and kept the box, returning it to his widow after the pianist’s death. For a major pianist who never recorded, the box contained more than a mere idea of his art.”

How fortuitous that that box of broadcasts was preserved, as the pianism captured is indeed stupendous. Eisenberger plays with an exquisitely refined sonority, magnificently shaped phrasing (what a natural rise-and-fall, as if spoken by a skilled actor), wonderful clarity of articulation and rhythmic pulse, and pedalling that never obscures the clarity of texture and the line.

Mieczysław Horszowski

Another example of recordings saved from destruction that show another side to the artist are some performances Evans issued of the Polish pianist Mieczysław Horszowski. In addition to a number of live recordings of the artist, Evans managed to rescue some 1940 Vatican radio recordings that were made at a time when the pianist was not making commercial recordings. An archivist at Vatican Radio transferred the Horszowski tapes just as they started to fall apart, and Evans was able to obtain and release these historically invaluable performances. Here is a stunning reading of Liszt’s Legende No.1, St. Francis of Assisi preaching to the birds.

Ilona Eibenschütz

This pupil of Clara Schumann was also a favourite pianist of Brahms, who chose to privately perform his Opp.118 and 119 for her alone. Evans released two sets of historical Brahms recordings and was very taken with the vivacious, unpretentious style of the fiery Eibenschütz, heard here in a performance captured when she was around 80 years old. What a soaring melodic line, rhythmic propulsion, expansive rubato, and clarity of texture – truly spirited yet sensitive artistry by a remarkably important figure in late Romantic pianism.

Leo Sirota

Another tremendous artist whose scarce recordings Evans released was Leo Sirota, an utterly fascinating pianist. Paderewski had hoped to teach the young Russian but the boy’s parents thought him too young, and he would later go on to study with Busoni in Vienna. He then lived in Japan for a period of 16 years starting in 1929, becoming a major figure in Western classical music in the country. However, being Jewish he was interned during WWII. Once the conflict had ended, his daughter moved to Japan as one of the few Americans fluent in Japanese and would help draft the new constitution, having a role to play on equal constitutional rights being granted to both genders.

This 1963 performance of Chopin’s Nocturne in B Major Op.62 No.1 comes from Sirota’s farewell concert tour of Japan and features lovely Romantic pianism, with fluid phrasing, amazing dynamic shadings, incredible pedalling, and truly spacious pacing: what freedom in his shaping and timing of the melodic line and how it interacts with the accompaniment.

You can read more about Sirota in recollections by his daughter on Allan’s website here:

Artur Schnabel

As it was Schnabel’s granddaughter Ann Mottier who arranged for Allan and me to meet in New York two years ago, it seemed appropriate to end this tribute with this superb and rare recording that I was totally unaware of until just after Allan’s passing. This performance was released by Evans some 30 years ago: a November 17th 1947 concert recording of Artur Schnabel playing Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.4 in G Major with Izler Solomon conducting the Columbus Philharmonic Orchestra. This rare broadcast performance was released on disc only once, on a Pearl CD set also featuring Schnabel’s 1930s studio accounts of the complete Beethoven Concertos with Malcolm Sargent conducting. Schnabel would rerecord Concerti 2 through 5 in the late 1940s in London, as well as 4 and 5 in 1942 in Chicago. A 1945 concert performance of the Third Concerto conducted by Szell circulated quite widely but the Pearl set is the only release I know of featuring this traversal of the Fourth.

The performance was recorded privately for the conductor on yellow-labeled lacquers. Because the discs had suffered some water damage on account of poor storage, several portions were unplayable. For those sections, Evans and transfer engineer Seth Winner patched the gaps with the relevant sections of Schnabel’s 1942 RCA recording with the Chicago Symphony. It is worth noting that the slow movement in this concert performance is significantly longer than in Schnabel’s studio accounts: 6:50, whereas the 1942 RCA version is 5:29 and the 1946 EMI version is 4:55. This gives an idea of how the time constraints set by the limited length of 78rpm discs impacted some of the pianist’s interpretative inclinations.

Schnabel’s playing throughout is glorious, with a truly luminescent sonority, marvellous pedal effects, rhythmic vitality, and wonderful interplay with the orchestra – a truly heartfelt and inspired performance.

Our thoughts are with Allan’s widow Beatrice, son Stefan, and their extended family and friends. Allan’s website Arbiter Records at arbiterrecords.org will be maintained and his extensive collection of materials will be preserved – no details are available at the moment but do stay tuned. RIP Allan and grazie mille for all your brilliant work.

One comment

What a good tribute to a wonderful and truly gifted man! Personally, I shall always feel his loss.