One of the great joys of running my Facebook page for the last 11-plus years is coming across great pianists I’d never heard of. In the past one had to find a record in a shop (in my case, usually second-hand) and take a gamble on whether to buy the disc, but now with YouTube and other online platforms we can unexpectedly find and quickly listen to artists we might never have encountered.

In December 2020 while browsing through YouTube I stumbled across a pianist that I had never heard of or heard before and it took me time to regain my composure, as the playing is in my opinion so staggeringly jaw-dropping that I am utterly flummoxed at how she could have been so forgotten.

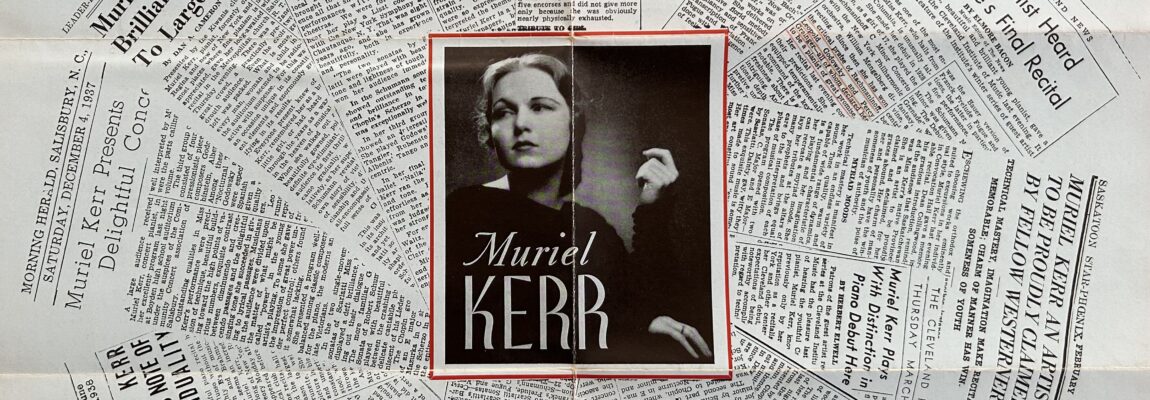

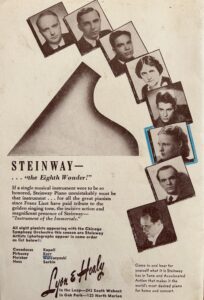

Muriel Kerr was a Canadian artist who ended up in the US, dying prematurely in 1963 at the age of 52. Born in Regina on January 18, 1911, Kerr studied initially with Paul Wells in Toronto, with Alexander Raab in Chicago, and with Percy Grainger (I’m not sure where or for how long). After a Canadian tour in 1922, she began an extensive period of studies in New York with Ernest Hutcheson – she became his favourite pupil and then his assistant for many years. She won the Schubert Memorial Competition at Julliard in 1928, which gave her the opportunity to record an RCA 78rpm disc (below) and to play the Rachmaninoff Second Concerto at Carnegie Hall with Willem Mengelberg conducting the New York Philharmonic on December 5, 1928, by which point Leopold Godowsky had proclaimed her ‘the most gifted pianist in America.’

She taught extensively throughout the US, beginning at Juilliard from 1942 to 1952 (David Bar-Illan was among her pupils). Her first European tour took place in 1948 and due to issues with management she put an end to a proposed tour the next year: she was represented by Columbia Artists and when she went to discuss the following year, the agent – with his feet on his desk – wanted her to repeat the exact same recital program she had played in every concert the previous year. Under the impression was that they simply didn’t want to print new programs, she walked out of the office.

She taught extensively throughout the US, beginning at Juilliard from 1942 to 1952 (David Bar-Illan was among her pupils). Her first European tour took place in 1948 and due to issues with management she put an end to a proposed tour the next year: she was represented by Columbia Artists and when she went to discuss the following year, the agent – with his feet on his desk – wanted her to repeat the exact same recital program she had played in every concert the previous year. Under the impression was that they simply didn’t want to print new programs, she walked out of the office.

She joined the faculty of the School of Music at the University of Southern California in 1955, where she would teach until her death in 1963, simultaneously acting as director of the Punahou Music School in Honolulu. Among her pupils there was Michael Tilson Thomas and she is quoted (here) as being a ‘glamourous tough cookie’ who suggested he bring his left hand to his next lesson.She still played throughout her teaching career: her pupil Neil Stannard wrote of a chamber music concert at USC in which she played the Brahms Piano Quartet in C Minor Op. 60 with fellow faculty members: Heifetz, Piatigorsky, and Primrose! That’s a pretty top-tier group of musicians right there … what I wouldn’t give to hear a recording of that performance.

Stannard shared that “her demonstrations were inspiring and thought-provoking. She was a musician’s musician and everyone loved her.” Another pupil who studied with her extensively could not speak highly enough about her beloved mentor. “Her legato, singing, balanced tone was unforgettable, but she had every sound in the pianist’s arsenal for every period of music. Hearing her play, one was struck first by that tone and then the intelligence in interpretation (she was always mindful of what note should dominate in a chordal texture). The music was the whole and only message… Her hands were of medium size, not large. Her movements at the piano were mostly close to the keys, and there were no extraneous movements used for showmanship. She had a warmth and dignity on stage as well as in person.”

Stannard shared that “her demonstrations were inspiring and thought-provoking. She was a musician’s musician and everyone loved her.” Another pupil who studied with her extensively could not speak highly enough about her beloved mentor. “Her legato, singing, balanced tone was unforgettable, but she had every sound in the pianist’s arsenal for every period of music. Hearing her play, one was struck first by that tone and then the intelligence in interpretation (she was always mindful of what note should dominate in a chordal texture). The music was the whole and only message… Her hands were of medium size, not large. Her movements at the piano were mostly close to the keys, and there were no extraneous movements used for showmanship. She had a warmth and dignity on stage as well as in person.”

As regards her teaching, she added, “Possessing the kind of intelligence artists of a high calibre have, plus a good command of English (not all teachers do), she was able to choose words that brought truth to the fore. She did demonstrate some passages but she didn’t use the instrument to get across meaning all the time. She often broke down passages that could be divided between hands and would suggest, ‘but you could play that with your left hand.’ She helped without judging and never admonished. Most importantly, she was interested in teaching the highest level of repertoire and getting us to understand each work’s specificities. In summary, she was a very great teacher.”

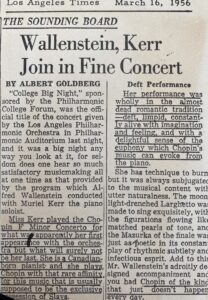

She continued to garner rave reviews for her appearances with orchestra and her solo recitals. A newspaper article by Patterson Greene (it is not clear in which newspaper) leading up to the concert whose programme is shown above provides some insight into Kerr’s interesting programming: “Miss Kerr, on general principles, does not align herself with those who use dates to establish sound barriers. Her taste is eclectic. In planning her programs she combines works that are compatible with one another. Their sequence is dictated by their essence, not by their place in musical chronology. For that reason, Hindemith will be followed by Beethoven: His set of Bagatellen Opus 126 – from the era of the late Sonatas and Quartets. The Schumann F Sharp Minor Sonata, a group of ‘Definitions’ by Beryl Rubinstein and a Chopin group – in that order – make up the unconventional bill of musical fare.”

Sadly, Kerr died suddenly as the result of an asthma attack on September 18, 1963 at the tragically young age of 52. She had been having a particularly hard time with asthma that summer and chose to spend that fateful night in the guest room to let her husband sleep. She went to the medicine cabinet in the middle of the night and must have had an asthma attack at the time, as her husband found her on the bathroom floor in the morning. Stannard was the first pupil to hear the awful news: he had arrived early to the fall semester registration to be sure that he could sign up for lessons with Kerr, only to be told by a shaken administrator that she had died the night before.

The high esteem with which Kerr was held by her colleagues is evidenced by the fact that the LA Philharmonic left their usual location to give a memorial concert dedicated to Kerr at USC’s Bovard Auditorium.

The high esteem with which Kerr was held by her colleagues is evidenced by the fact that the LA Philharmonic left their usual location to give a memorial concert dedicated to Kerr at USC’s Bovard Auditorium.

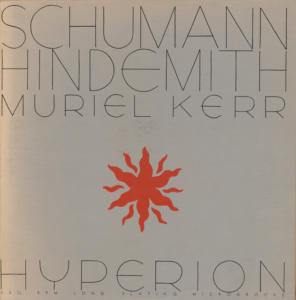

Kerr recorded her sole 78 in 1928 – only one of the two Scriabin works on the disc has been reissued – and a single LP in 1951 on the small Hyperion label, featuring works by Schumann and Hindemith; the latter was reissued on RCA Victor after she died, royalties for this ‘special products’ LP to be contributed to the Muriel Kerr Memorial Scholarship Fund at the USC. It is indeed lamentable that this great artist should have a recorded output lasting barely 40 minutes, and it is certainly to be hoped that some broadcast performances will be found and made available – fortunately, some private chamber recordings have been found and are available below for the first time ever.

Aged 17 at the time she cut her RCA Victor 78, Kerr plays with the authority and command that characterizes the playing on her LP recording, qualities referenced in most concert reviews (a review of her 1945 New York recital featuring the Liszt Sonata compared her to the legendary Teresa Carreño). With long lines in lyrical passages and clarity of texture throughout, Kerr’s playing features consistently beautiful tone, marvellous pedal technique, and wonderful dynamic control.

The first recording of Kerr that I came across on YouTube was some Schumann from a transfer of the memorial RCA Victor LP and I was mesmerized from beginning to end – the upload had a mere 35 views at the time, tragic in my opinion given the absolute mastery on display in the playing. Fortunately, the piano community kicked into high gear when I posted excitedly about the artist on my Facebook page: within 24 hours I had not only received the 78 transfer (now replaced with a newer transfer by Tom Jardine, to whom all thanks) but also a much cleaner transfer of the RCA vinyl (gratitude to Hugo David Vazquez Merritt!), which I have now uploaded to YouTube and embedded below. I have opted to present the Schumann portions prior to the Hindemith (reverse order to the RCA vinyl) as that appears to have been the ordering on the original Hyperion LP.

The first recording of Kerr that I came across on YouTube was some Schumann from a transfer of the memorial RCA Victor LP and I was mesmerized from beginning to end – the upload had a mere 35 views at the time, tragic in my opinion given the absolute mastery on display in the playing. Fortunately, the piano community kicked into high gear when I posted excitedly about the artist on my Facebook page: within 24 hours I had not only received the 78 transfer (now replaced with a newer transfer by Tom Jardine, to whom all thanks) but also a much cleaner transfer of the RCA vinyl (gratitude to Hugo David Vazquez Merritt!), which I have now uploaded to YouTube and embedded below. I have opted to present the Schumann portions prior to the Hindemith (reverse order to the RCA vinyl) as that appears to have been the ordering on the original Hyperion LP.

We can hear in her stunning performance of the Schumann Novelette Op. 21 No. 8 that Kerr had stupendous technique, additionally playing with blazing passion and truly refined musicality. Her magnificent tone, stunning clarity of texture, gloriously sculpted phrasing, mindful use of dynamics, and impeccable timing – particularly at transitions – all captivate me. For those who find it harder to recognize the refinement in her playing amidst the intensity in this first performance on the disc, her account of the Fantasiestücke No. 2 in A-flat Major Op. 111 reveals to perfection her gorgeous tonal colours, sumptuous legato phrasing, clarity of texture, and soaring phrasing, while the Fantasiestücke No.1 in C Minor Op. 111 also receives a masterful performance, with incredible momentum that highlights the work’s inner intensity without being overly driven, with that distinctive clarity of phrasing and texture that characterizes her other recordings. As for the Hindemith, Kerr’s traversal of his Piano Sonata No.3 is as lyrically phrased and transparent in texture as her Schumann.

I am delighted to share two private recordings of Kerr playing chamber music, from a white label LP provided by her student and transferred by Hugo David Vazquez Merritt. The other performers are violinist Sascha Jacobsen (concertmaster of the LA Philharmonic), violist Paul Robyn, and Kerr’s cellist husband Naoum Benditzsky. The recordings appear to have been made in a studio setting (there is no audience noise or applause) and the ensemble is absolutely terrific, Kerr’s pianism shining with her characteristic clarity of texture, masterful phrasing, and rhythmic vitality. Here is Mozart’s Piano Quartet No.1 in G Minor, K. 478:

The flip side of the record is a superb account of Beethoven Piano Quartet in E-Flat, Op.16 with the same artists, with the same cohesiveness and marvellous playing on the part of each:

Renowned pianist Kirill Gerstein became fascinated by the artist when he saw my Facebook posts and started doing his own online digging, in so doing coming across this 1953 WNYC interview with the pianist, in which she speaks about using music education to help disabled veterans – a wonderful testament to her dedication as a teacher:

In May 2023 I was contacted by someone who had seen this tribute page who had inherited a significant volume of Kerr documents from the pianist’s nephew, and he generously sent me the sizeable package. Included were concert programs and newspaper clippings dating back to the 1920s, promotional flyers, concert programs, and personal and professional photographs. I will add a few of these to this page and more biographical details once I am able to sort through them more systematically but at this time I have added a few of the images from this amazing collection.

I will be adding to this page as information and recordings make themselves available, so if anyone out there knows anything else about this artist or has any unissued recordings, please let me know. In the meantime, I hope you will enjoy the truly superb playing of this utterly remarkable musician, sadly taken from us much too soon.