It is remarkable that a pianist whom Busoni said was among his greatest disciples could be forgotten to the extent that many fans of piano playing today have never heard of him, but this is sadly the case. Leo Sirota was not just one of the legendary pianist-composer’s three favourite pupils – alongside Egon Petri and Ignaz Friedman (although the latter’s primary teacher was Theodor Leschetizky) – but was also esteemed as a friend and colleague. Yet despite a major international career spanning six decades, the previously revered Russian pianist is far less remembered today than many of his contemporaries.

As is so often the case, one major factor is quite simply the lack of recordings: he made barely an hour’s worth for the Homochord label in the mid 1920s (including the first ever complete account of Schumann’s Etudes symphoniques) and another half hour in the 1930s while in Japan (including the first ever complete Petrouchka Suite), but he did not produce a single disc in the LP era, despite his having lived until 1965. Fortunately the relatively recent availability of some 1950s and 60s broadcast recordings has enabled his playing to reach a new audience and has brought awareness of the art and life of a man who played a major role in the dissemination of classical pianism in the first half of the 20th century.

Early Years

The pianist seemed destined for greatness from a very young age. Born Leiba Gregorovich Sirota on May 4, 1885 in Kamenezk Podolsk in present-day Ukraine, he was attracted by the playing of the pianist Michael Wexler, who lived in the same home and to whom the young boy would gravitate whenever he practiced. After some lessons at home, he was taken to the Imperial Music School in Kiev to study with Chodorwski (Horowitz’s future teacher Tarnowski was in the same class). He gave his first tour at the age of ten and so impressed Paderewski that the legendary Polish pianist invited him to Paris to study with him, an offer that was declined because the boy’s parents found him too young. Glazunov took him under his wing and upon Leo’s graduation, the famed composer wrote a letter of recommendation to Busoni with the suggestion that the young man train with the legendary Italian composer-pianist in Vienna.

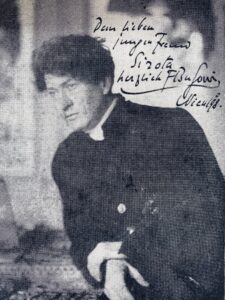

And so in 1904, the 19-year-old Sirota set off for Vienna – but he wanted to decide for himself who he should study with. He played for Hofmann, Paderewski, Godowsky, and Busoni: all four accepted him and he chose Busoni, and when Sirota belatedly presented him with Glazunov’s letter, the Italian is said to have stated, ‘What need is there for this? I have heard you play!’ The high esteem in which he was held by the composer is evidenced by a tale that after Sirota played the Don Juan Fantasy at a master class, Busoni shut the piano lid and stated that he did not wish to listen to anyone else play that day; he then took a copy of his recently-published Elegies from his desk and inscribed it, “To my young colleague from Kiev, for the Don Juan Fantasy on May 4th, 1908 in Vienna … Herzlich [cordially] … Ferruccio Busoni”. The date indicates that this was the pianist’s 23rd birthday, and the legendary composer’s use of the word ‘colleague’ was understandably moving to the artist as well.

Here is a broadcast recording of Sirota playing that work nearly 50 years later, a mere 6 weeks before his 70th birthday, still demonstrating a wonderful fusion of virtuosity and musicality:

Auspicious Debuts

Sirota’s solo Vienna debut took place on December 27, 1909 in a recital that included the Hammerklavier Sonata and ended with the Don Juan Fantasy. On February 8, 1910 he made his Berlin debut with a programme that sounds as though it was the same as his Vienna recital:

Beethoven Hammerklavier Sonata

Brahms Paganini Variations

Chopin: Two Etudes Op.10, Nocturne Op.48, Mazurka Op.59, Ballade No.1 [the selections in each opus grouping are unclear]

Mozart-Liszt Don Juan Fantasy

Despite rave reviews and the fact that he was already successfully performing, Sirota chose to enter the Anton Rubinstein Competition in St. Petersburg that year; Arthur Rubinstein was a participant and in his memoirs singled out Sirota, Edwin Fischer, Leff Pouishnoff, and another as pianists who ‘depressed me – they played too well. All four had the kind of technical polish which I never possessed. And they never missed a note, the devils.’ None of them would win a prize – Alfred Hoehn came out on top – and as we know, these artists went on to highly successful international careers, though it is Fischer and Rubinstein, both of whom recorded extensively, who are most remembered today.

One of the landmark concerts in Sirota’s career took place later that year at the Musikvereinsaal, in December 1910 – a massive and rather unusual programme: Sirota played the Don Juan Fantasy before joining Busoni for a performance of the Two-Piano Sonata in D Major, and then he played the titanic Busoni Piano Concerto with the composer conducting the Tonkünstler Orchestra with the Männergesangverein Chorus participating in the fifth movement’s choral performance.

Sirota wrote of the event, “How I came to play Busoni’s Concerto is rather an interesting story. I had planned to make my debut in Vienna under the baton of the of the noteworthy conductors of that time. Since Busoni was not only my former master but also a most excellent conductor, and because of his immense popularity throughout the European continent, I decided that I must persuade him to come to Vienna. I, therefore, quickly wrote to him, offering to perform his Concerto, which had never been performed before at a concert in Vienna. Busoni quickly replied, making all the necessary arrangements, and indicating any specifications he had in mind. It was September and the performance was slated for early November [sic]. I immediately set to work, practicing eight hours a day during the entire six weeks before the concert, and when the night arrived, I walked out onto the stage without so much as a single rehearsal. Busoni was overjoyed at the success. We received sixteen curtain calls.”

Sirota wrote of the event, “How I came to play Busoni’s Concerto is rather an interesting story. I had planned to make my debut in Vienna under the baton of the of the noteworthy conductors of that time. Since Busoni was not only my former master but also a most excellent conductor, and because of his immense popularity throughout the European continent, I decided that I must persuade him to come to Vienna. I, therefore, quickly wrote to him, offering to perform his Concerto, which had never been performed before at a concert in Vienna. Busoni quickly replied, making all the necessary arrangements, and indicating any specifications he had in mind. It was September and the performance was slated for early November [sic]. I immediately set to work, practicing eight hours a day during the entire six weeks before the concert, and when the night arrived, I walked out onto the stage without so much as a single rehearsal. Busoni was overjoyed at the success. We received sixteen curtain calls.”

The pianist would travel around Europe but continue to be based in Vienna, continuing to work with Busoni throughout the war while studying philosophy, law, and music history at the University of Vienna. He helped his friend Jascha Horenstein, then training to be a conductor, by playing for him on Sundays and would eventually be introduced to the conductor’s sister Augustine. At a dinner the pair attended at Busoni’s home, while Leo spoke with Mrs. Busoni, the composer spoke highly of Sirota to Augustine, telling her what a nice man and wonderful musician he was. They were married soon after.

Sirota traveled extensively throughout Europe, at times in a Rolls Royce built for the King of Romania, and he was so well known in Vienna that mail addressed to ‘Leo Sirota, Vienna’ would be delivered to him. While performing throughout Russia, he was invited to give a tour of Manchuria: he took the Trans-Siberian railway and upon arrival was greeted by a special train elaborately decorated with greenery and adorned with posters of the pianist, complete with his own salon car and two additional carriages for attendants, plus another car with a Steinway. There are differing accounts as to how he met Japanese composer Kosaku Yamada while on that tour, but what is clear is that he made a previously unscheduled visit to Japan in the autumn of 1928 (not 1929 as has been reported) and gave more than a dozen concerts over the course of a month that were rapturously received.

The Far East

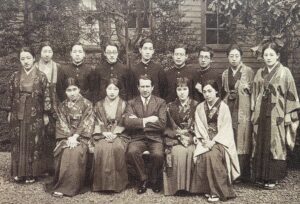

Sirota made such an impression in Japan that after his return to Europe he was offered to head the piano department at the Ueno Imperial Academy in Tokyo, while offers for concerts in the US were arriving. Instead of visiting the new world, Sirota opted to move to Japan with his family – surely not anticipating when he accepted the six-month post that he would remain for sixteen years. He became a beloved teacher, one of two major European pianists teaching there (the other was Leonid Kreutzer), and both his teaching and playing were highly acclaimed. Interestingly, Sirota was the first to play a Yamaha piano in concert – the brand-conscious Japanese had a preference for the more established European instruments – and he so significantly helped the company establish their reputation that they furnished him with pianos wherever he went.

Rave reviews were common, such as one in the Japan Times in 1933 that stated, “for him, no difficulty exists: he does with the piano what he wishes. The instrument like a faithful slave obeys and expresses every shade of his feeling, showing to his listeners whole series of tone pictures.” There were, however, signs that not all were aligned with Sirota’s aesthetic: occasionally a review might criticize his ‘passion’ while advocating ‘calm objectivity’, and critic Junji Kakei noted in 1937 that the Russian pianist represented more of the ‘old school’ of personal interpretations rather than the emerging preference for a more objective approach to performance:

Mr. Sirota’s expression lacks the freshness to lead and enlighten us. It lacks elastic naturalness. The rhythms are sometimes distorted by his arbitrary individualistic flourishes. I have no doubt that Mr. Sirota has the technique of a maestro but maybe he imagines he cannot be a signpost for us of the younger generation … This evening’s Liszt concert was a superficial success. If we feel any dissatisfaction about it, however, I think the chief reason was that Mr. Sirota failed to look back at every aspect of this great pianist Liszt from a modern point of view.

Nevertheless, despite such outlying reviews, he was very successful and was certainly beloved by his pupils. Despite some inherent linguistic barriers, Sirota was able to demonstrate effectively at the keyboard how they could improve their playing and they achieved noticeable results. However, things would take a turn during the Second World War. As Beate left in 1939 to go to college in California, the Japanese secret police began keeping tabs on foreigners living in Japan. The Sirotas made a visit to the US in mid 1941 and sailed back that November on the last ship that left the States prior to Pearl Harbour being bombed. Their absence raised questions and Leo was interrogated as to why he had mailed letters in the US on behalf of a friend. German officials in the country had all Jews in prominent positions removed from their posts and Sirota was thus barred from performing and broadcasting.

Leo and Augustine were with other expatriates sent to the mountain village of Karuizawa, where they experienced a drastic change from the more luxurious conditions in which they had previously been living: their rural home was very cold (minus 15 degrees Celsius in the winter) and food was scarce. One day, a farmer recognized Sirota as he had not only attended one of the pianist’s concert years earlier but been so moved that he had brought home one of the posters of the event. Although local residents were to have no contact with interned foreigners, at great personal risk the farmer provided the Sirotas with extra food and helped them as much as he could.

In 1945, three secret police agents came to arrest Sirota but a colleague of theirs intervened and said they would be back the following week; Sirota believed he would be taken to be executed. Within days, the atomic bombs were dropped and the war ended. Beate, as one of the few Americans completely fluent in the Japanese language, got a job with the Foreign Economic Administration working for General MacArthur and was able to go to Japan to find her family and ensure their safety. She was tasked with helping draft the new constitution of the country and played a significant role in the inclusion of a clause regarding legal equality between men and women, which endeared her to the Japanese for the rest of her life (read more here).

The New World

After a few farewell concerts (and a polite refusal to resume his teaching post), Sirota and his family moved to the US in 1946, initially settling in New York. In 1947 the master pianist finally gave his Carnegie Hall debut – almost four decades after his European debuts. He was invited to St. Louis and accepted a post on the piano faculty at the St. Louis Institute of Music, taking over from another Busoni pupil, Gottfried Galston. Over the course of the next 15 years or so, Sirota gave many broadcasts on the radio – including the complete piano music of Chopin and Schumann, the complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas (the first pianist to do so on radio in the US), and a Liszt series – but he made no commercial recordings.

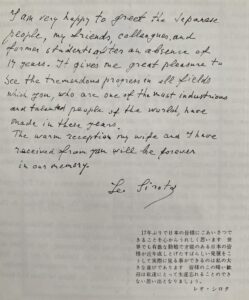

At the age of 78, Sirota finally consented to requests that he return to Japan and in late 1963 he gave a farewell tour where he played solo recitals and conducted concerto performances in which his students appeared as soloists. The three-week trip was described by the pianist as ‘like a wonderful dream.’ Alas, it was to be his last tour. Plans were underway to celebrate his 80th birthday in May 1965, but he fell ill a few months earlier, complaining of tiredness in early February. Within weeks, he died of liver cancer and aggravated diabetes, on February 24, 1965.

Rediscovering A Legend

Sirota made about an hour’s worth of recordings for the Homochord label between 1924 and 1926 (Gieseking also recorded for them) and also produced some discs for Japanese Columbia within a year of his arrival in the country a few years later. These were all but forgotten until the mid 1990s, when the Dante label produced a reissue in their series devoted to historical piano recordings. The Japanese label Green Door came out with a 3-disc set that included some of these 78s together with later recordings of unknown provenance. Pianophile Allan Evans would befriend Sirota’s daughter Beate, who made available to him a number of private tapes that were taken from both American broadcasts and the pianist’s 1963 farewell tour of Japan. He included a few tracks in two Busoni and his Circle CDs on the Pearl label and then issued three discs entirely dedicated to Sirota on his own Arbiter label. After Evans passed away, the Japanese label Sakuraphon was tasked with releasing more Sirota items from the family archive, and as of Autumn 2024 two volumes have been released (available here).

Among the pianist’s official recorded output is one important world premiere: the first complete account on disc of Schumann’s Etudes symphoniques Op.13, including posthumous variations. Despite the lamentable sound – perhaps the recording, the remastering, or a combination thereof – we can appreciate the pianist’s nobility of conception, refinement of tone, deftness and consistency of articulation, combination of power and musicality, and clarity of voicing.

It was Sirota who premiered Stravinsky’s Trois mouvements de Petrouchka when Arthur Rubinstein, the pianist for whom the composer had penned the work, found himself unable to master the suite’s technical challenges (Rubinstein never recorded it commercially but a 1961 concert recording exists). Sirota set down an account for Japanese Columbia in his early years in Japan – the first on record – demonstrating great dexterity yet always playing with beautiful tone, his rhythmic pulse steady without being rigid – the musical content is always primary.

Despite the faded sound in these early recordings, we can recognize some true brilliance and mastery in Sirota’s playing. His 1924 recording via the acoustical process [with a cone-shaped horn instead of a microphone] of the Glinka-Balakirev ‘The Lark’ reveals a gorgeous singing tone, seamless phrasing, magnificent pedalling, and magnificent nuancing. What glistening runs and poised presence!

Fortunately there are some later recordings of the pianist in vastly better sound that help us appreciate the full extent of his artistry. If he was past his prime – as might be expected when he was in his 60s and 70s in these performances – he nevertheless maintained his impressive dexterity and, more importantly, demonstrated depth of musicianship that was both innate and the result of his wealth of experience in a career that had that point been over half a century.

Because Sirota recorded primarily shorter works (with the exception of the Schumann Op.13 and Stravinsky Petrouchka) in his studio sessions, hearing him in larger scale repertoire from a range of historical periods gives us a greater idea of his interpretative capabilities. This performance of Beethoven’s Sonata No.18 in E-Flat Major Op.31 No.3 from his farewell tour of Japan finds the 78-year-old playing with tremendous command both technically and musically, and we get a glimpse into another world of piano playing. Sirota was still decidedly ‘old school,’ though his individual touches are not as overt as some from his generation or soon before; there are, nevertheless, some fascinating nuances such as gentle timing adjustments at transition points.

Sirota had the entire Chopin solo works in his repertoire (it is to be hoped that his 1950s broadcasts are preserved and will be issued) and the composer’s music provides the ideal vehicle for his brand of individual pianism. In this 1952 broadcast, he plays the opening measures of the Fantaisie F Minor Op.49 with a wonderfully full and transparent bass sonority, presenting the themes with disarming simplicity and beauty of tone, eschewing bombast as the work builds in tension while still playing with remarkable strength and power. A terrifically exciting yet musical performance!

As the Chopin Fantaisie above, this 1954 broadcast of Liszt’s Après une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata features grand and noble playing by the 69-year-old Sirota, powerful and impassioned without being either overbearing or sentimental, his massive sonority and broad gestures never compromising musical content and clarity.

It is often in works that are seemingly simple that we can recognize an artist’s mastery. These two short works from Stravinsky’s Three Easy Pieces are delivered with a wonderful lilting rhythm, mindful use of articulation and dynamics to highlight the quixotic nature of the music, an absolutely gorgeous sonority, and magnificent phrasing. What a whimsical performance!

There is only one recording of Sirota playing with orchestra that has been made public, a recent upload to YouTube: a June 24, 1955 St. Louis concert performance of Weber’s Konzertstück Op.79 with his brother-in-law Jascha Horenstein conducting. Sirota’s astounding pianism is readily discernible despite the sonic limitations of the recording: a month after his 70th birthday, he plays with incredible fire, with a depth of tone that never devolved into harshness in louder passages while also going down to a whispering pianissimo without losing its singing quality, and with remarkable rhythmic vitality and beautifully shaped phrasing. It’s also quite meaningful to hear these two musicians together some forty years after they met, especially given their familial connection.

To close this tribute to this remarkable pianist, a performance of Chopin’s Nocturne in B Major Op.62 No.1, from Sirota’s 1963 farewell concert tour of Japan. This reading features fluid phrasing, amazing dynamic shadings, incredible pedalling, and truly spacious pacing: what freedom in his shaping and timing of the melodic line and its interplay with the accompaniment.

To learn more about Sirota, there is an English translation of a Japanese book available on Amazon (print-on-demand or instant Kindle download) which is a very enjoyable and insightful read. Some of the Arbiter CDs may still be available but apparently some are out of print (you can check to see if iTunes/Apple Music will work for you) – there is certainly some worthy reading about him on the Arbiter website. The pianist’s daughter Beate wrote a marvellous book detailing her role in drafting the Japanese constitution, which also gives some fascinating biographical background about the family. Let us hope that more of the pianist’s playing and personal history will be made available!