After a friend’s piano recital last year, a post-concert conversation amongst a few attendees took a fascinating turn. A teacher mentioned hearing students state a preference for interpretations that are ‘clean.’ We got into an amazing discussion of various things that both students and scholars tend to overlook, such as portamenti in string playing, rubato, and the shaping of phrasing. Some of what is found in early recordings can sound unusual to present-day listeners, yet it is remarkable to me how many trained musicologists, professors, and performers consider such means of expression ‘dated’ – a truly comical choice of words when speaking of music which, having been written a hundred or more years ago, is by definition dated. We discussed the challenge of bringing music to life without injecting something into it but rather by drawing something out of it, not blindly copying what was done in the past but being informed of what was the norm and what options are available today.

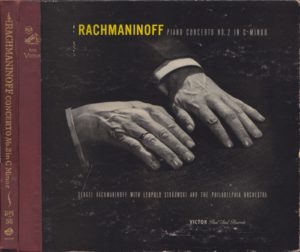

I recounted how when I presented historical recordings at the local university, some students balked at Rachmaninoff’s use of rubato when playing a Chopin Nocturne, despite his having been born in the century in which the music he was playing had been composed. It fascinated me that the students’ response indicated a subconscious belief that their perspectives on what rubato was appropriate was more ‘correct’ than that of a legendary pianist from the 19th century – why else would the students find the playing this old record ‘strange’ if they did not hold the belief that their way was the ‘right’ way? It was all the more fascinating when considering that these were students who loved and played Rachmaninoff’s own music – and yet they had reservations when the beloved composer-pianist’s playing differed from their own vision.

I recounted how when I presented historical recordings at the local university, some students balked at Rachmaninoff’s use of rubato when playing a Chopin Nocturne, despite his having been born in the century in which the music he was playing had been composed. It fascinated me that the students’ response indicated a subconscious belief that their perspectives on what rubato was appropriate was more ‘correct’ than that of a legendary pianist from the 19th century – why else would the students find the playing this old record ‘strange’ if they did not hold the belief that their way was the ‘right’ way? It was all the more fascinating when considering that these were students who loved and played Rachmaninoff’s own music – and yet they had reservations when the beloved composer-pianist’s playing differed from their own vision.

I am not saying we should imitate what was done in earlier eras, but should we not at least know what musicians of the past really did by listening as opposed to simply reading descriptions? I recall that the students’ objections came to a very sudden end when I asked, ‘And what if we found a recording by Chopin and you didn’t like the way he played? What would the implications be?’ Their jaws dropped and I could see their minds instantly open as they realized that their stated goal of doing justice to ‘the composer’s intent’ was at odds with their attitude towards playing that varied from their expectations, which were themselves formed by what is the norm in our era. They were far more receptive and engaged to what they heard in subsequent recordings.

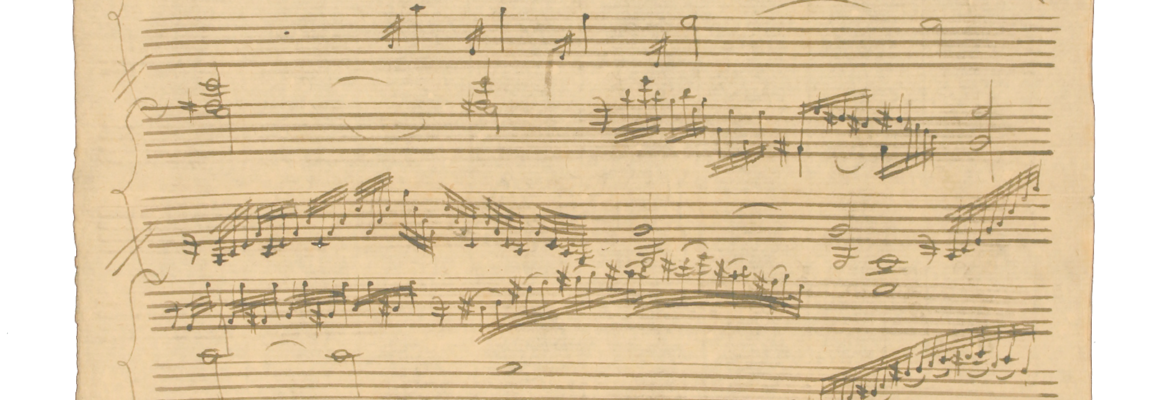

One of the most important recordings to have come to light and been released (very recently) is a fascinating one appropriate to this discussion. It may be the rarest piano recording ever and I think it is one of the most remarkable: a disc recorded ca. 1921 of the forgotten composer-pianist Josef Labor playing part of a Beethoven Sonata. Labor was born in 1842, a mere 15 years after Beethoven died, and was a celebrated pianist, organist, composer, and teacher. His more famous pupils include Arnold Schönberg, Alma Mahler, and Paul Wittgenstein, and he was a close friend of Brahms, Richard Strauss, and King Georg V of Hannover. He was also blind since childhood due to smallpox. While he was revered in his time, he has largely been forgotten by musical history … as was the fact that in the early 1920s, close to age 80, this man raised in Viennese culture not far removed from Beethoven’s time made two records on the obscure Union label of Austria. Gregor Benko of the International Piano Archives had never heard of Labor until the sole known copy of one of the discs found its way to him a few years ago via John Maltese Jr.; Benko tells the tale of its discovery, along with an assessment of its importance, on the Marston Records website page for the compilation on which it was released (click this link).

In Labor’s playing, we hear the fascinating use of timing, accents, and dynamic shifts to bring more dimension to this slow movement of Beethoven’s Sonata No. 7 in D Major Op. 10 No. 3. (Because only one of the two records Labor made has been found, the opening of the movement is missing.) This performance has been met by more academic-minded listeners with less enthusiasm – and that is certainly their right – and I am not suggesting that we emulate this kind of playing. However, listening – and more than once – is essential: when listening for the first time, our reaction to what is different from the norm and our preferences can prevent us from neutrally and accurately hearing and assessing what is happening, so our biases can limit the full apprehension of what is actually taking place. The more one listens, the more one hears. I recently played this recording for a Japanese violinist and his eyes widened as he said, ‘He’s revealing his soul and the soul of the music.’ This is indeed playing that needs to be heard more than once – and, keep in mind the question: if a recording were found of Beethoven playing, is there any guarantee that you would like it? And if not, what would that mean when it comes to your preferences and the role of the performer?

How incredible that in 2019, we can hear pianism preserved nearly 100 years ago of a man who was born almost 180 years ago. The playing is not just radically different in style from what we hear today but in intent. It is important to remember that there was a time when music was inextricably linked to live performance: because recording technology did not exist, if people wanted to hear music, they played it at home or went to a concert… they did not listen to music ‘in the background’ – it was a conscious, lived experience. The listening to and playing of the music were part of the same event, and the performer was expected to bring the work to life in an individual way. The notes and markings were a guide, but the music needed the interpreter to interpret it. Several kinds of inflections and means of expression were not marked in the score because such ‘touches’ were the norm at the time. Composers also did not need to dictate (or micro-manage) every nuance, nor would they have thought this worthwhile, as doing so would go against the nature of music and performance as they knew it.

Another Beethoven performance that some university students attending my presentations had initially found ‘extreme’ was this glorious 1936 broadcast of Josef Hofmann playing Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata (available here): they couldn’t imagine playing Beethoven with such rubato. But when one listens to rubato separate from tonal colours, dynamics, the balance with other voices, and musical structure, of course it can sound extreme – people tend to listen to one plane of expression alone as opposed to the multi-dimensional fabric of which the tempo is but one thread. But when adjusting timing simultaneously with dynamics, colour, and texture, it is not a one-plane shift in musical expression but a multifaceted one.

Hofmann’s individual music-making is absolutely fascinating, harking back to an age when performers who were both skilled and informed not only expressed their individual perspectives but were expected to. We don’t go to the theatre to hear the words of a script dictated, and it isn’t the blueprint alone that makes a house a home but how it is brought to life by the individual expression of those inhabiting it. Just as earlier styles of fashion and design can seem archaic in the present day, what is done today will one day be subjected to similar derision (although one need certainly not wait to disagree with contemporary norms). Whether one likes Hofmann and other performers of his generation or not, attempting to play music from previous centuries without hearing actual recordings by the greatest artists of the past borders on negligence.

It was the fact that Rachmaninoff recorded his own music that woke me up to the existence and importance of historical recordings some 30+ years ago (read more here) but this doesn’t mean that a composer’s way is the only way – or that composers even had only one approach that they never deviated from. However, the existence of recordings which preserve ‘fixed’ interpretations has bred into our culture and mindset the belief that there is one unwavering way to play a piece of music and that any artist should have such a fixed perspective, which would make each concert but a photocopy of each other performance they give. But great performers and composers such as Rachmaninoff were not so rigid in their own readings, even if there was a general conception that they had of a work.

It was the fact that Rachmaninoff recorded his own music that woke me up to the existence and importance of historical recordings some 30+ years ago (read more here) but this doesn’t mean that a composer’s way is the only way – or that composers even had only one approach that they never deviated from. However, the existence of recordings which preserve ‘fixed’ interpretations has bred into our culture and mindset the belief that there is one unwavering way to play a piece of music and that any artist should have such a fixed perspective, which would make each concert but a photocopy of each other performance they give. But great performers and composers such as Rachmaninoff were not so rigid in their own readings, even if there was a general conception that they had of a work.

Rachmaninoff made his recordings in the era of 78rpm discs, which did not allow for precision editing (every 4-to-5-minute segment was recorded ‘as is’), so multiple versions were made of each ‘side’ so that the best of each could be chosen for the commercial release; concertos usually consisted of four or five two-sided records (for Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No.2, for example, it was five discs comprising ten ‘takes’). It seems that starting in the 1940s, RCA had been repressing some earlier recordings from their catalogue using existing alternate takes instead of those approved by the artists, apparently doing so to avoid overusing the ‘master’ metal stamper.

In the case of Rachmaninoff’s 1929 traversal of his own Piano Concerto No.2, it became apparent in the 1980s that all republications of the recording, from the 1940s right through the LP era, had used alternate takes for 9 out of the 10 sides – amazingly not only the initial 1950s LP transfers on RCA but also their 1973 centenary The Complete Rachmaninoff collection! Incredibly, the first long-playing release of the approved takes was RCA’s 1987 CD release! The upshot of this is that there are essentially two different performances of Rachmaninoff playing this work – and, naturally, not every nuance is exactly the same. So even in the case of a composer’s performance, not every reading was the same.

Here is Rachmaninoff’s ‘alternate’ reading:

There is at least one musicologist who thought that Rachmaninoff’s recordings should be disregarded because he deviated from the score… the score that he himself wrote. Let that sink in a little bit and consider the insanity and repercussions of that perspective … especially when one ponders the reasons a composer might choose to do things differently. Some insight in this regard comes from a pianist who strongly believed that the score was not sacrosanct: Jorge Bolet. The Cuban-born pianist was present for the rehearsals prior to Rachmaninoff’s first performance of his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, and he saw the composer realize in the course of playing with orchestra for the first time that certain things did not sound the way he had imagined. Rachmaninoff made revisions on the spot, but those changes were not incorporated into printed editions of the score because it had already been published. Therefore, the score as printed does not accurately convey the composer’s true wishes and those who follow it are actually not doing what the composer wanted – how’s that for irony? ‘So much for Urtexts,’ stated Bolet when recounting this tale and showing his own annotated score to his pupil Ira Levin.

The great pianist elaborated on the role of the performer in realizing a composer’s intentions in this brilliant interview (starting 2 minutes in this clip, after a fine performance of a Chopin-Godowsky Etude):

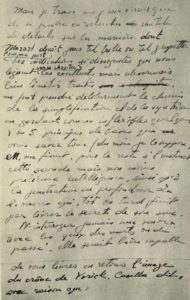

Bolet advised being faithful to the music more than to the score, a position shared by the legendary pianist Dinu Lipatti. Held up as a pianist who respected the score – and he did – Lipatti is often considered a proponent of more ‘objective’ playing, but he was not averse to making changes to the text. However, he did so in the same vein as Bolet, referring to the UrSpirit as being more important than the Urtext. This might seem to be at odds with the writing that follows, which was part of a draft for a master class on interpretation that Lipatti was to give together with Nadia Boulanger in the Spring of 1951 (alas, he died a few months earlier), but in fact it is not. His writing here reveals some fascinating concepts, though not the whole picture of his perspectives:

It is unjustly believed that the music from one era or another must preserve the imprint, the characteristics, and even the vices prevalent at the time this music was created. In thinking this way we have a peaceful conscience and find ourselves incapable of any dangerous misrepresentation. And to reach this objective, for all the effort, for all the research done in the dust of the past, for all the useless scrupulousness towards the ‘sole object of our attention,’ we will always end up drowning it in an abundance of prejudices and false facts. For, let us never forget, true and great music transcends its time and, even more, never corresponded to the framework, forms, and rules in place at the time of its creation: Bach in his work for organ calls for the electric organ and its unlimited means, Mozart asks for the pianoforte and distances himself decisively from the harpsichord, Beethoven demands our modern piano, which Chopin – having it – first gives its colours, while Debussy goes further in presenting through his Preludes glimpses of Martenot’s Wave. Therefore, wanting to restore to music its historical framework is like dressing an adult in an adolescent’s clothes. This might have a certain charm in the context of a historical reconstruction, yet is of no interest to those other than lovers of dead leaves or the collectors of old pipes.

It is unjustly believed that the music from one era or another must preserve the imprint, the characteristics, and even the vices prevalent at the time this music was created. In thinking this way we have a peaceful conscience and find ourselves incapable of any dangerous misrepresentation. And to reach this objective, for all the effort, for all the research done in the dust of the past, for all the useless scrupulousness towards the ‘sole object of our attention,’ we will always end up drowning it in an abundance of prejudices and false facts. For, let us never forget, true and great music transcends its time and, even more, never corresponded to the framework, forms, and rules in place at the time of its creation: Bach in his work for organ calls for the electric organ and its unlimited means, Mozart asks for the pianoforte and distances himself decisively from the harpsichord, Beethoven demands our modern piano, which Chopin – having it – first gives its colours, while Debussy goes further in presenting through his Preludes glimpses of Martenot’s Wave. Therefore, wanting to restore to music its historical framework is like dressing an adult in an adolescent’s clothes. This might have a certain charm in the context of a historical reconstruction, yet is of no interest to those other than lovers of dead leaves or the collectors of old pipes.

These reflections came to me while recalling the astonishment that I caused some time ago when I played, at a prominent European music festival, Mozart’s D minor Concerto with the magnificent and stunning cadenza that Beethoven made for this work. True, we could sense that the same themes appear differently under Beethoven’s pen than under that of Mozart. But this is exactly wherein lies the appeal of this interesting confrontation between two such different personalities. I regret to say that other than a few enlightened spirits, nobody understood this marriage and everyone suspected that I had composed this vile and anachronistic cadenza!

How right Stravinsky is in affirming that ‘Music is the present’!

Music has to live under our fingers, under our eyes, in our hearts and in our brains with all that we, the living, can offer it.

Far be it for me to promote anarchy and disdain for the fundamental laws which guide, along general lines, the coordination of a valid and pertinent interpretation. But I find it a grave mistake to lose oneself in researching useless details regarding the way in which Mozart would have played a certain trill or grupetto. As for myself, the diverse markings provided by excellent yet incomplete treatises compel me to decisively take the path to simplification and synthesis while immutably preserving some four or five fundamental principles of which I think you are aware (or at least, I suppose you are), and for the rest I rely on intuition, that second but no-less-precious intelligence, and to in-depth penetration of the work, which, sooner or later, ends up confessing the secret of its soul.

Never approach a score with eyes of the dead or the past, for they may bring you nothing more in return than the image of Yorick’s skull. Alfredo Casella rightly said that we must not be satisfied with merely respecting masterpieces, but we must love them.

Lipatti was not saying that it is a waste of time to research how Mozart was played in his era: he states that is a ‘grave mistake to lose oneself in researching useless details.’ I would add that one should not lose oneself in useful details either, as details alone do not paint the full picture and ‘losing oneself’ would render any potentially useful details useless. Lipatti was certainly historically informed, yet he also played in a very present-time way – how else to explain his radically unconventional approach to Bach’s D Minor Concerto BWV 1052? He not only incorporates some of the variants that Busoni had penned for the work but uses dynamics and voicing in a fascinating way: pay particular attention to the magnificent decrescendo in the first movement (from 6:39 to 7:02), where he reveals the magic of Bach’s writing by highlighting the chromatic progressions while also reducing the volume in a way that seems absolutely logical.

There are those who believe that Bach should not be played with such dynamic variation because this was not possible on the harpsichord. However, several of Bach’s keyboard concertos were transcribed for violin and for oboe; the composer himself transcribed these compositions so they could be played not just on the harpsichord but also on instruments capable of adjusting dynamics and lyrical phrasing. That should make it obvious that he would be happy if his keyboard music were played on a keyboard capable of more lyrical and dynamic expression as well. It’s incredibly shortsighted and unimaginative to believe that this is not the case – and Bach himself was hardly shortsighted and unimaginative!

There is no one correct approach to the issue of how one should perform the music of the past. It was all once new and now it isn’t; indeed, the composers whose music we still play today likely had no idea that we would still be listening to and performing their music centuries later. So many factors have changed – not just the instruments but the size of the spaces in which the music is performed and heard, as well – and one cannot recreate the past, and nor should one want to. It is up to the performer to find their way and lead the listener home to the heart of the music. I am convinced, however, that composers would not want performance to simply reproduce the printed notes on the page but rather to bring the music to life. How best to do that is the art of interpretation … which is certainly more than just the skill of reproducing notes.

One thing is certain: we are fortunate that so many incredible historical recorded performances are now so readily available. Long may we listen, learn, and enjoy!

Comments: 2

Magnificent, Mark. I am going to make this required reading for my music history students. BTW, do you know Lipatti’s wonderful advice on preparing for performance? It was from a letter sent to a young student,

Thank you so much for your lovely comment, Joel – I’m so touched that you’ll be sharing it with your students. There’s no one way or right way… but we need to ask some questions and at times sit with the question even when there’s no real answer.

I do know that Lipatti text – another one that I’ll have to put online too, for easy reference. There’s also a fascinating July 1950 radio interview in which he writes about his way of approaching a new work – it’s on YouTube (in French) and I’ve also translated it into English on the dinulipatti.com website.

Thank you once again for your lovely comment!