The Polish pianist Maryla Jonas is one whose name has all but been forgotten except by the most ardent piano fans and record collectors. First pressings as well as early LP discs of her 78rpm recordings – particularly a 1955 Columbia Entre LP featuring a set of Chopin Mazurkas made in the late 1940s – continue to fetch top dollar at shops and auctions. But beyond the legendary tale of her movie-like biography is a level of pianistic expression that is utterly magnificent and unique.

Much of the biographical material about Jonas contains some erroneous details. Born Maryla Jonasówna in Warsaw on May 31, 1911, she debuted as a child prodigy prior to the age of 10 (her age varies depending on the account). Reports that she won the 1932 International Chopin Prize are thoroughly inaccurate: she didn’t place in the 1927 competition and she came in 13th in 1932, also winning a diploma in the 1933 Vienna Competition, where Lipatti famously, much to Cortot’s consternation, tied for second; other diploma winners in Vienna include Gina Bachauer, György Sandor, and Karl-Robert Kreiten (who perished at the hands of the Nazis and whose memory still brought Claudio Arrau to tears decades later). In Brussels in 1938, she participated in the Eugène Ysaÿe International Music Competition – now the Queen Elisabeth Competition – and didn’t place in the top 12. On the basis of her competition standings, one wouldn’t think she would become a pianist whose scant recordings would be lauded into the next century.

What is clear (from her own admission) is that her suffering due to personal losses in the war would infuse her playing with a depth that cannot be learned in conservatories. Jonas was rounded up with other Jews in Warsaw in 1939, but a German officer who had previously heard her play in Germany released her. She is said to have made her way to Berlin on foot (a distance of over 300 miles), an arduous journey that was so incredibly taxing that it would lead to health problems that plagued the pianist for the rest of her short life. Contacts at the Brazilian embassy arranged for her to join her sister who had moved there several years prior to the war: Jonas was smuggled into Brazil with forged papers claiming that she was the wife of a diplomat and was reunited with her sister before news reached her that her husband, parents, and a brother had died in the camps.

What is clear (from her own admission) is that her suffering due to personal losses in the war would infuse her playing with a depth that cannot be learned in conservatories. Jonas was rounded up with other Jews in Warsaw in 1939, but a German officer who had previously heard her play in Germany released her. She is said to have made her way to Berlin on foot (a distance of over 300 miles), an arduous journey that was so incredibly taxing that it would lead to health problems that plagued the pianist for the rest of her short life. Contacts at the Brazilian embassy arranged for her to join her sister who had moved there several years prior to the war: Jonas was smuggled into Brazil with forged papers claiming that she was the wife of a diplomat and was reunited with her sister before news reached her that her husband, parents, and a brother had died in the camps.

Jonas was unconsolable and refused to play the piano, reportedly being admitted to a sanatorium to recover from her psychological stresses. It has been said that her admirer and compatriot Arthur Rubinstein lured her back to the piano by asking her to help him check the acoustics prior to his recital in Rio, and that once she touched the piano she couldn’t stop playing; apparently the audience had started to enter before she realized that she had been at the keyboard for hours and was not alone with Arthur. The enthusiastic response by those who heard her led her to be booked to perform a recital of her own.

Jonas was unconsolable and refused to play the piano, reportedly being admitted to a sanatorium to recover from her psychological stresses. It has been said that her admirer and compatriot Arthur Rubinstein lured her back to the piano by asking her to help him check the acoustics prior to his recital in Rio, and that once she touched the piano she couldn’t stop playing; apparently the audience had started to enter before she realized that she had been at the keyboard for hours and was not alone with Arthur. The enthusiastic response by those who heard her led her to be booked to perform a recital of her own.

While it has been stated that she spent extended periods of time recovering from her emotional turmoil, she in fact played her debut in Rio earlier than has been reported, as this news clipping from June 18, 1940 indicates: she was due to to perform on June 29, not long after she had arrived in the country. Whether her time recuperating was before or after this performance is unclear. Jonas did not seek out the limelight, though the impresario Ernesto de Quesada arranged concerts for the pianist in South America and eventually in New York, where her success would launch the most prolific period of her career.

With successes at Carnegie Hall in New York in early 1946 – the virtually empty hall on February 25 was full when she reappeared on March 30, thanks in no small part to a rave review in the New York Herald Tribune – Jonas signed a contract with Columbia Records that found her in the studio as early as April 19 producing discs that have in the intervening years cemented her reputation amongst piano connoisseurs. Among the works recorded at her first session is this reading of the Mazurka in F Minor Op.68 No.4, with phrasing is dramatically forged through varying key pressure and articulation, a phenomenally pure and focused singing sonority, elegant nuancing, and marvellous timing, with a wonderful rhythmic lilt and gorgeous rubato:

The fabled Columbia Entré LP issued September 26, 1955 features some of Jonas’ late 1940s recordings of Mazurkas, which captures her idiomatic approach to these seminal works, the varying moods beautifully characterized and played with a simplicity that belies the pianistic and musical skill required to phrase with such directness and purity of tone. While these works might not be technically challenging when it comes to playing the notes, to capture the right mood and play with such seeming directness is no small feat. Jonas accomplishes the Herculean task with elegance, grace, wit, and tenderness:

It is little wonder that this LP is still prized by collectors – though present-day listeners can fortunately now purchase Jonas’ complete discography in a marvellous four-disc set issued by Sony, remastered from the source material for the first time and issued with a lavish booklet and slip covers that are replicas of some of her vinyl releases.

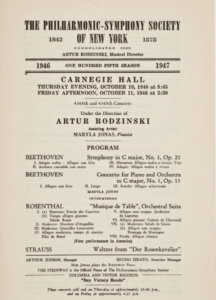

Sadly, Jonas’ complete discography comprises a mere four CDs (the recordings could actually fit on three) and there aren’t any large-scale works among them, the longest single composition being Schumann’s Kinderszenen, which is itself made up of shorter pieces. There was indeed some criticism during her brief career for the absence of more substantial repertoire in her programmes, and one laments that none of her concerto broadcasts seem to have survived (she made her New York Philharmonic debut in October 1946 with Beethoven’s first Concerto – and while a recording of Wanda Landowska playing Mozart’s Piano Concerto K.415 two weeks later has been found and issued, there is no trace of a Jonas aircheck).

However, one can learn more about piano playing and interpretation in a single mazurka reading by Jonas than one can in many readings of longer, more ‘profound’ works by many other pianists. While the scale of works she played might have been limited, her musical depth was anything but.

Jonas would largely give up performing in 1951, after a fainting spell while playing Carnaval in a Carnegie Hall recital led her to believe herself unfit to continue in the public eye, though she would have two more recording sessions a few months later, on May 9 and May 17, 1951. The following year she was diagnosed with a rare blood disease that would ultimately kill her less than a decade later. She made one final appearance in concert, a Mozart and Chopin performance at Carnegie Hall in December 1956. She died on July 3, 1959 at the age of 48 – her second husband died three weeks later.

Another wonderful example of her pianistic mastery is gorgeous reading of Mendelssohn’s Song without Words Op.102 No.4 from that next-to-last Columbia session of May 9, 1951, played with a dramatically arched melodic line and fluid legato phrasing that is as seamless as it is beautiful in tone and shaping. To think that this exquisite example of her pianism was produced at a time at which she had given up performing:

Sony Classical’s exceptionally well-produced The Maryla Jonas Story is a must-have for lovers of fine piano playing, containing the first ever official release of her complete discography, remastered from the source material (read my review here) – a fitting tribute to a truly exceptional pianist whose playing deserves repeated listening.