This is a revised form of an article that was published in the Summer 1999 edition of International Piano Quarterly. It has been updated with information that has since come to light.

Dinu Lipatti is one of the most mystical of pianists, yet over a half century after his premature death, most pianophiles know little more than the sketchy biographical information published with the frequent reissues of his critically lauded recordings. He received no more than a parenthetical mention in the classic tome The Great Pianists, Harold C. Schonberg’s only comment being that “his death in 1950 at the age of 33 took away a pianist who would have been one of the major figures of the century.” Such observations overlook the fact that before his death, Lipatti was already considered one of the greatest pianists and musicians to have graced the concert stage.

Exploding the Myth

Stories about the dramatic nature of his suffering at the hands of leukemia have often overshadowed his uniquely profound musicianship. Dinu Lipatti was in fact a far more modern, revolutionary, and dynamic pianist than his ill health or the limited scope of his few recordings would indicate. He is still generally thought of as a Bach-Mozart-Chopin pianist, yet his repertoire ranged from Bach to Bartok, Scarlatti to Stravinski, and he publicly performed some 23 works for piano and orchestra. A champion of modern music (he was a talented and successful composer himself), as a student he performed concerts of Romanian music in 1930s Paris with the likes of Szigeti and Enescu, and he gave the Swiss premiere of the Bartok Third Concerto with Ansermet (the orchestral scores arrived the day of the concert, and by all accounts it was a stellar performance). If his sickness prevented him from concertizing overseas (Malcuzynski was his last-minute replacement on a three-month Australian tour in 1949), Lipatti did perform all over Europe, from London to Bratislava and Helsinki to Rome, under conductors as varied as Abendroth, Ackermann, Ansermet, van Beinum, Bigot, Boehm, Hindemith, Karajan, Mengelberg, Munch, Sacher, and Scherchen.

Unique programmes

Unique programmes

Despite his overall physical weakness, Lipatti’s endurance on stage could be phenomenal, and his unorthodox programming indicates that he was not quite the frail, overly cautious purist many believe him to have been. What pianist today plays two concertos per concert? In his late teens in Bucharest Lipatti played the Mozart D Minor Concerto with Stravinski’s Capriccio (the critic felt that his playing was more suited to the Stravinski than to the Mozart!), and in his later years he coupled the Liszt E Flat Concerto with either the Mozart D Minor, Martin Ballade, or Chopin Andante Spianato and Polonaise, and would pair the Bach-Busoni D Minor or Haydn D Major Concertos with the Ravel G Major Concerto – what incredible juxtapositions of style! He created a stir when, at the 1947 Lucerne Festival under Hindemith’s baton, he performed the Mozart D Minor Concerto with Beethoven’s cadenza; while the concert was viewed as the highlight of the festival, Lipatti was accused of having written the “evil and anachronistic cadenza.”

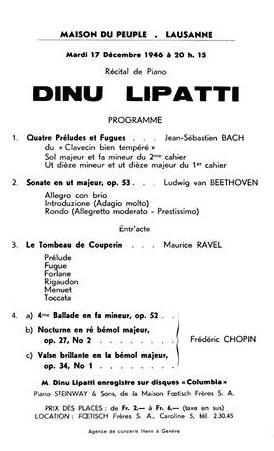

His solo programmes were equally bold and varied. He performed in one recital four Preludes and Fugues of Bach, Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata, Schumann’s Etudes Symphoniques, and Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin. One 1947 Chopin recital was a heroic survey of the composer’s works: 6 Preludes, 3 Etudes, Sonata Op.58, Ballade op.52, Mazurka Op.50 No.3, Scherzo Op.20, Nocturne Op.27 No.2, Waltz Op.34 No.1, and Polonaise Op.22. At other times, his recitals focused on one large-scale work, such as the Waldstein, Chopin B Minor Sonata, or the Etudes Symphoniques, the rest of the programme being a historical progression of smaller-scale compositions from Bach through Chopin, Brahms, Liszt, and through to modern composers like Debussy, Ravel, de Falla, and Enescu.

Fact vs. Fiction

If Lipatti’s career and repertoire were more expansive than has previously been believed, it should also be noted that some of the most famous anecdotes regarding his recordings and repertoire are completely false.

Myth No.1: Lipatti would not record the Tchaikovsky Concerto unless he had three years to prepare it, and he would require four years for the Emperor Concerto.

Fact: An internal memo from Lipatti’s recording producer, the legendary Walter Legge, dated February 23, 1948 says that “Lipatti has his heart set on doing a Beethoven Concerto in 1949” and proposes a recording of the Emperor (which Lipatti had performed twice in Bucharest in the 1940-41 season); another dated June 7, 1948, addressing a proposed Tchaikovsky Concerto recording for Columbia, finds Legge presenting “the ideal solution for this problem. Lipatti has agreed to record this work in 1949 in London with Karajan.” (This was eventually shot down in favour of a recording with Malcuzynski.)

Myth No.2: Lipatti agreed to play the Beethoven Waldstein Sonata within the last two years of his life at Artur Schnabel’s suggestion when Legge introduced the two pianists.

Fact: Lipatti had performed the Waldstein regularly since 1935, making the first of many broadcasts of the work the following year, and he knew Schnabel well before he met Legge. (It was Edwin Fischer who, in 1943, taught Lipatti “the daring way in which Beethoven indicated the use of the forte pedal” in the last movement.)

Accolades from the musical elite

The extraordinary clarity of his playing and the probing musicality of his interpretations earned Lipatti the recognition and admiration of the musical luminaries of his time. Pianists such as Backhaus, Cortot, Fischer, Haskil, Kempff, and Schnabel were friends and supporters, as were musicians from other fields in music – Ansermet, Boulanger, Cuenod, Dukas, Enescu, Honegger, Markevich, Menuhin, Munch, Poulenc, Toscanini… Cortot, noting Lipatti’s “exceptional gifts,” called him “a real revelation on the horizon of pianists,” writing on his death, “There was nothing to teach you. One could, in fact, only learn from you.” When Frank Martin first heard Lipatti play, he “felt that something unusual was happening, that I had never heard the piano played like this.” Poulenc labeled him an “artist of Divine spirituality,” and Honegger said that he was “above all a musician and, secondly, a pianist.” Karajan described his playing as “no longer the sound of the piano, but music in its purest form.”

The extraordinary clarity of his playing and the probing musicality of his interpretations earned Lipatti the recognition and admiration of the musical luminaries of his time. Pianists such as Backhaus, Cortot, Fischer, Haskil, Kempff, and Schnabel were friends and supporters, as were musicians from other fields in music – Ansermet, Boulanger, Cuenod, Dukas, Enescu, Honegger, Markevich, Menuhin, Munch, Poulenc, Toscanini… Cortot, noting Lipatti’s “exceptional gifts,” called him “a real revelation on the horizon of pianists,” writing on his death, “There was nothing to teach you. One could, in fact, only learn from you.” When Frank Martin first heard Lipatti play, he “felt that something unusual was happening, that I had never heard the piano played like this.” Poulenc labeled him an “artist of Divine spirituality,” and Honegger said that he was “above all a musician and, secondly, a pianist.” Karajan described his playing as “no longer the sound of the piano, but music in its purest form.”

No less than Toscanini became a great admirer upon hearing Lipatti in the Chopin E Minor Concerto at La Scala in 1946, first in rehearsal – Lipatti had asked the maestro if he would offer some “severe criticism, which he readily agreed to do,” (oddly enough) – and then in concert, proclaiming “At last we have a Chopin sans caprices and with the rubato to my liking.” They developed quite a friendship, with Dinu and Madeleine being extended a rare invitation to attend his rehearsals (“these were rare moments of joy and encouragement for me,” wrote Dinu), and they spent more time together later in Lucerne.

Colleagues and admirers

The high esteem in which Lipatti was held by many great pianists is a true testimony to his artistry. He had met Edwin Fischer when he was a student in Paris, and was offered assistance any time he should visit Berlin; years later in Switzerland, they would meet and play for each other whenever they could. Clara Haskil, with whom he became lifelong friends, wrote “you are a very great artist and soon all your famous colleagues will be put in the shade by you.” Artur Schnabel declared that Lipatti’s playing was “an entirely new way of playing the piano” and attended several of his concerts. He was devastated by his death, writing of “a very real and personal loss. I admired and liked that boy immensely… He was one of the most attractive personalities I have known in my life.”

He was obviously an extremely congenial individual and a musician of tremendous capabilities, and his playing has continued to captivate listeners through the widespread release of his commercial and live recordings. Biographical information provides a fascinating look at his formative influences and his achievements, and hitherto-unpublished information regarding his recording career and analysis of his pianistic approach cast new light on this most unique musician and his artistry.

Early studies and beyond

There was never any doubt that Dinu Lipatti would devote his life to music. His proud, musical parents picked up on his natural talent right away, and with Georges Enescu as his godfather, his environment catered to his calling. Born March 19, 1917 in Bucharest, Romania, young Dinu (Constantin was his birth name) started studying piano with his mother at the age of four and was soon composing evocative descriptions of family members. At eight he was under the supervision of local legend Mihail Jora, and he was eleven when he entered the class of Florica Musicescu at the Bucharest Academy.

There was never any doubt that Dinu Lipatti would devote his life to music. His proud, musical parents picked up on his natural talent right away, and with Georges Enescu as his godfather, his environment catered to his calling. Born March 19, 1917 in Bucharest, Romania, young Dinu (Constantin was his birth name) started studying piano with his mother at the age of four and was soon composing evocative descriptions of family members. At eight he was under the supervision of local legend Mihail Jora, and he was eleven when he entered the class of Florica Musicescu at the Bucharest Academy.

While much has been made of Lipatti’s later studies with Cortot, that the French master felt that he had nothing to teach him was undoubtedly due to the thoroughness with which Musicescu instilled in Lipatti a monumentally comprehensive technique, an unrelenting critical ear, and deep understanding of his responsibility as a performing artist. The teacher of other fine pianists such as Radu Lupu and the nearly forgotten Mindru Katz, Musicescu was apparently somewhat of a tyrant, and if Lipatti occasionally went home in tears, his respect for and faith in his teacher were undying. He remained in contact with her for his entire life.

An unusual win

By the time he entered the 1933 Vienna International Music Competition at the age of 16, he had performed the Grieg, Chopin E Minor, and Liszt E-Flat Major Concertos to great acclaim. Romanian critics were already pinpointing the very qualities for which Lipatti’s playing continues to move listeners today, noting that he was “endowed not only with a splendid technique, but also with spiritual qualities, a fine grasp of the works performed, and a great desire to achieve the correct interpretation.” His participation in the competition would, rather backhandedly, prove to be a launching pad for his career.

The distinguished jury was a who’s-who of the piano world, including Arrau, Backhaus, Cortot, de Greef, Dohnanyi, Erdmann, Friedman, Gieseking, Hess, Landowska, Michalowski, Ney, Phillipp, Rachmaninoff, Rosenthal, and von Sauer. In the final round, it was a toss-up between Lipatti and Poland’s Boleslav Kon; because the latter would soon be beyond the age limit for competitions (and as Lipatti was so young), he was awarded first prize, and Lipatti tied for second with the USSR’s Mykyscha Taras. (Other finalists included Gina Bachauer and Gyorgyi Sandor.) Cortot was indignant about the use of non-musical criteria in the decision-making process, and is reported to have resigned from the jury in protest (this is, in fact, not clear, but his vocal objection certainly is). When given the choice between attending the awards ceremony or a recital given by Cortot the same evening, Lipatti opted for the recital, nevertheless reporting with characteristic modesty that the first prize “went to a Pole who possessed great experience, assurance, and calm.”

Paris in the ‘30s

It was not until the fall of 1934, after another year of studying and performing in Bucharest, that Lipatti moved to Paris – possibly not at Cortot’s invitation but at the suggestion of his mother, who went with him. When Lipatti did go to play for Cortot at the Ecole Normale de Musique, he was immediately recognized and invited to study piano with Cortot and his assistant Yvonne Lefebure, and composition with Paul Dukas. He would later study conducting with Charles Munch, and after Dukas’ death his composition teacher was Nadia Boulanger, who became his “spiritual mother.” (Like Musicescu, she too was capable of acts of tyranny, and years later, when she continued to reduce students to tears by having them play Bach fugues with the parts reversed, it was reported that only Lipatti had done so successfully.)

Lipatti enjoyed a prosperous period of study and performing, being invited to the musical salons and concertizing successfully in Paris and nearby European cities. Critics did not know “what to praise most, his technical mastery or his profound musical understanding.” Lipatti’s elegantly-phrased reviews of concerts by Horowitz, von Sauer, Kreisler, and others, published in Romania’s Libertatea, reveal his acute sensibility and awareness regarding the changing direction of musical performance (“today we witness a tendency towards absolute technical perfection devoid of any sensitivity or elan”) and the influence of “public opinion, which remains eternally superficial, dependent on trends made fashionable by snobbery and publicity.”

The winds of war

At the outbreak of the war, Lipatti returned to Romania, and continued to enjoy a career as a soloist (he performed the Liszt First Concerto with Mengelberg) in addition to beginning a two-piano partnership with his future wife, Madeleine Cantacuzene. Concerts were given in destinations such as Bratislava, Sofia, Vienna, Berlin (where “severe characters dressed in black… barely raised their eyebrows when they smiled – I liked them”), and Rome. While he wrote of a tour in March 1943 that was to find him performing throughout Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Germany with the likes of Abendroth and Boehm, he apparently did not go – concert programs exist for performances he made at that time in Romania. (Friedrich Wuehrer performed on at least one of the scheduled occasions.)

On September 4, 1943, Lipatti left Romania with Madeleine, provisionally on a ten-day tour, and never returned. After a blown engine led to an emergency landing in Hungary, he traveled to Vienna, Stockholm, and Helsinki before giving a tour of Switzerland, enjoying such unprecedented success that he remained for some time in Switzerland. The following year, Lipatti was offered an honorary professorship at the Geneva Conservatory; although some “colleagues” had lodged a protest based on political ideologies, Lipatti was supported by Ansermet, Martin, and others, and in April 1944 he began his role as professor of the Classe de Virtuosite, a position he held for five years.

A mysterious illness

It was shortly after his arrival in Switzerland that the first signs of a mysterious illness appeared. It started out as a persistent fever, and after some time he was treated with X-ray therapy. He remained in precarious health for the rest of his life (he had been somewhat weak since childhood and as such his general education had taken place at home), and baffled doctors, in their desperate attempts to find a solution, administered esoteric treatments that brought about serious side effects. Around the time of his Columbia recordings he underwent mustard-gas injections, which caused such immense swelling in his left arm that his suits needed altering to hide the disfiguration; Lipatti joked that he could now produce “such formidable sonorities in the bass that even Miss Musicescu would be satisfied!” He had only one working lung (“my lung of existence”), and by 1947 had been diagnosed with lymphogranulomatosis, a form of leukemia known as Hodgkin’s Disease.

Despite frequent cancellations caused by ill health, Lipatti concertized throughout Europe in halls packed with audiences who had heard talk of a pianist who brought unimaginable depth to his interpretations. The musical world outside of Europe began to learn of Lipatti when the release of his Columbia recordings started in 1947. The Schumann Concerto was particularly well-received (even if Lipatti wasn’t too happy with the “super-classical” Karajan’s tempi), but about a month after it was recorded in April 1948, Lipatti fell gravely ill and for a year and a half gave only a handful of concerts. He was having weekly blood transfusions, and in 1949 was forced to abandon his teaching post. He prepared a “less tiring programme” (Bach Partita No.1, Mozart Sonata No.8, 2 Schubert Impromptus, and the Chopin Waltzes) and dropped grander works from his repertoire in order to conserve his strength. Admirers held onto their tickets in the hope that he would appear despite official cancellations. By the end of 1949 Lipatti was performing more, albeit sporadically, continuing to mesmerize audiences with what one contemporary referred to as “a different kind of expression.”

A ray of hope

In the Autumn of 1949, Lipatti’s friend and colleague Paul Sacher and his wife heard of the success of cortisone treatment in America and, when the Swiss doctors gave their approval several months later, obtained the very best pure leaf extract (at the then-exorbitant cost of eighteen pounds a day) with the help of other Lipatti admirers. The success was startling: “Just think of it, I’m still marvelously well,” he wrote his benefactors. “It’s an unheard-of feeling.” Recording equipment was sent to Geneva to capture Lipatti’s playing as he enjoyed an unprecedented remission and return to vitality.

But after this brief flash of optimism, his condition deteriorated (doctors had dared give the injections for no more than a month) and he gave only two more concerts, performing the Mozart Concerto K.467 in Lucerne with Karajan and a final solo recital in the small French town of Besancon, both of which were recorded and posthumously issued. The most famous story of Lipatti’s career, sadly, is the fact that he was too weak to perform the last of the fourteen Chopin Waltzes he had programmed; after a brief absence from the stage he played “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” instead, as a final offering.

Dinu Lipatti died on December 2, 1950 – not of the leukemia which had plagued him for years, nor from the various medical treatments which had ravaged his body, but because an abscess on his one working lung, having gone unnoticed by his doctor that very day, burst. He was 33 years old.

The recordings

Lipatti’s international renown and reputation today come, for the most part, from his incredible EMI recordings, and it is a virtually unknown fact that this association almost never came to be. In January 1946 one Sidney Beer was in Switzerland signing artists to Decca, and Dinu Lipatti was at the top of his list (which also included Furtwaengler, Richard Strauss, and Backhaus). Decca hoped to organize a tour for Lipatti, and over a two-month period “make a large number of recordings. It [was] proposed to record piano concertos of Chopin and other composers.” When EMI learned of this, they quickly intervened (they had not followed through on a previous offer to Lipatti) and won the artist to their Columbia sub label. After his first failed recording session in Zurich (a new material the company was experimenting with resulted in noisy surfaces), Lipatti would go to London three times to record before his final sessions in Geneva.

The few recordings Lipatti did make for Columbia (totaling about 3 1/2 hours) are of remarkable musicianship and interpretative depth, and that we do not have more is due not only to cancellations brought about by Lipatti’s sickness, but also to an overall lack of foresight regarding the seriousness of his condition and the great importance of capturing a comprehensive cross-section of his repertoire on disc. It has already been shown how Lipatti was prepared to record the Emperor Concerto and the Tchaikovsky Concerto, despite stories indicating otherwise. Other recordings which had been proposed (and in one case, made) are mouth-watering to be sure.

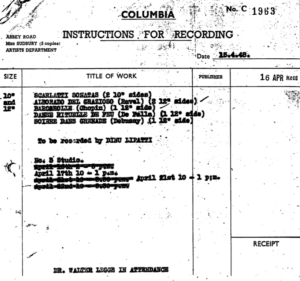

Lost opportunities

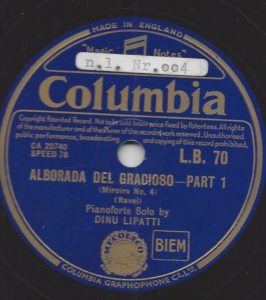

An “Instructions for Recording” sheet dated April 15, 1948 lists as items to be recorded at four sessions two Scarlatti Sonatas (he had already recorded two the previous year), the Chopin Barcarolle, Ravel’s Alborada del Gracioso (thus dismissing the tale that the work was recorded on a whim), Debussy’s Soiree dans Grenade, and de Falla’s Ritual Fire Dance. Two of the dates are crossed out, and Lipatti is only known to have recorded the Chopin and Ravel titles. (The Barcarolle was rejected and issued posthumously.) A memo dated April 21, 1948 – the day the Barcarolle was recorded – finds Legge writing that “Lipatti has made a special request to record the Schumann Etudes Symphoniques,” a work in his active repertoire at the time. Although the request was promptly approved, it appears that the recording was not made.

He did record six 78 sides accompanying the cellist Antonio Janigro (as a “test for Mr. W. Legge,” according to the recording sheets) at the Zurich Wolfbach Studio on May 24, 1947, when the artists were performing a series of chamber music recitals. Among them are the first movement of the Beethoven Third Cello Sonata and a movement of a Bach Cello Sonata. (A complete set of pressings is known to exist in private hands, yet only two sides from another source could be obtained for release a few years back.) On a similar note, Lipatti had also been asked to record the Chopin Cello Sonata with Gaspar Cassado, but was said to be “unavailable.”

Other recordings which had been planned include the Busoni Indian Fantasia and the Mozart C Major Concerto K.467. The Bartok Third Concerto (with Karajan) and the Chopin Waltzes were scheduled for November 1949; a suggestion to record in Switzerland was overturned, and Lipatti never made it to London. An emphatic plea to send equipment to record Lipatti in the Chopin E Minor Concerto came from the Jecklin Pianohaus, Zurich on February 21, 1950; this too never transpired. It would not be until July 1950 that equipment would be sent to Geneva and that Lipatti would make his valedictory recordings of Bach, Mozart, and Chopin.

The final sessions

It should be noted that he was presented with two pianos for these sessions – one Hamburg Steinway concert-grand from the Jecklins, and another short grand donated by admirers. According to Walter Legge, Lipatti opted for the latter, his “virgin, whom no other hands have caressed,” despite the fact that Legge had a “rooted objection to the lack of warm bass that seems inevitable in recordings made with short grands.” However, both Bela Siki and Jacques Chapuis, who visited the studio during the sessions, stated that it was indeed a grand piano, but that the small size of the studio creates the impression that a short grand was being used. As a result, the widely celebrated recordings, while of exceptional beauty and musicality, do not reveal Lipatti’s spacious tone and subtlety of articulation to the degree as would have a recording in a more spacious studio; this is particularly noticeable in the Chopin (a comparison with the 1947 recording of the A-flat Waltz makes this clear). How ironic that when Lipatti as in such vibrant health, he made recordings of his “less tiring programme” on what sounds like a sub-concert grand piano!

Lipatti’s pianism

Lipatti’s pianism is remarkable in how it expresses profound truth with utter simplicity, and is characterized by the crystalline clarity with which both structure and character are revealed. His interpretations go beyond the limited framework of the piano with his flawless command of pianistic technique – not simply digital accuracy but purity of tone regardless of the dynamics (his range was enormous), crisp precision of articulation, accenting without distortion of the melodic line, steadiness of rhythmic pulse, clarity of texture in voicing, and subtlety and timing of pedaling. That melodic lines are so deftly sculpted and presented in such stark relief is due to his ability to vary the attack used by different fingers, even within the same hand. The voicing of all lines is thus thoroughly consistent, and inner voices do not distract from the main subject; each line becomes an individual voice with its own unique timbre, together forming a choir of interdependent entities, each weaving its pattern in a tapestry of exquisite complexity.

His playing is immaculate – the balance, timing, and significance of every phrase, nuance, and harmonic progression has been considered and mastered, yet his performances exhibit warmth and passion and are free of the air of academic over-analysis. He presents each work under his fingers with such disarming simplicity that the music seems to be speaking freely through him, as though he were a receiver through which the composer’s intended message (of which the text is but a shadow) were being transmitted from the source of its inspiration – hence one French critic’s comment that he “heard Chopin himself interpreting his Sonata in B minor”. This does not mean that he was a literalist, however, and examples abound of changes he made to the text. He spoke, however, of the greater importance of the “Ur-spirit” as opposed to the Urtext, often telling his students that “if you are well brought-up, you can put your feet on the table and not offend anyone.”

A variety of approaches

Dinu Lipatti grasped and clarified the idiom of every composer whose works he played, and consequently his entire discography is worthy of examination. His ability to present the structure of a work with both the architectural overview of a blueprint and the spirit of a living being renders his Bach performances particularly worthy of attention, not least an unorthodox interpretation of the D Minor Concerto with selected Busoni variants: the perfectly steady decrescendo near the end of the first movement, with chromatic progressions in the outer voices superbly highlighted, puts an end to any audience noise in the Concertgebouw and will keep present-day listeners on the edge of their seats.

Recordings have been issued of Lipatti in two works of Mozart, the C Major Concerto K.467 and the A Minor Sonata K.310, and his performances of both exhibit the youthful innocence with tragic undertones that characterized the lives of both the composer and the interpreter. In his Chopin recordings, rhythmic pulse is subtly maintained, tempo shifts are beautifully choreographed (the transition into the coda of the D-flat Nocturne, the middle section of the Barcarolle, and the first movement of the Third Sonata are prime examples), and inner voices which cooperate rather than compete with the principal subject emerge clearly with pure singing tone. The middle section of the E Minor Etude is a miracle of balance and texture, the long melodic line never-ending, enveloped in cascading waves of harmonies. Lipatti’s virtuosity is put to dramatic yet musical use in his recording of the Grieg Concerto (the first movement cadenza is particularly spellbinding) and in all of his Liszt performances. The cadenza in the Allegro animato of the Liszt First Concerto, with its rumbling bass and carefully arched phrasing, has never sounded so sinister, and the Sonetto del Petrarca No.104 is of remarkable sensuality (the tonal control in the coda is breathtaking).

Contemporary champion

Lipatti’s performances of 20th Century music fully reveal the qualities that make all of his recordings so astounding. The transparency of his voicing and his rich, tonal palette demonstrate that dissonance need not be aggressive, but that it is simply a delayed resolution based on different laws than those used by earlier composers. Rather than hammering out a discordant note, Lipatti burnishes it and draws attention to its placement and how it is subsequently resolved. The chorale of the Adagio religioso of the Bartok Third Concerto is a stunning example, as chords reveal themselves to be clusters of tone vibrations (“music in its purest form”), each with its own particular flavour, colour, and message. The Third Sonata of Enescu, a work of extraordinary complexity, receives a stunning interpretation in which Lipatti is able to rapidly shift soundscapes to create a collage of tonal and atmospheric effects.

Lipatti’s performances of 20th Century music fully reveal the qualities that make all of his recordings so astounding. The transparency of his voicing and his rich, tonal palette demonstrate that dissonance need not be aggressive, but that it is simply a delayed resolution based on different laws than those used by earlier composers. Rather than hammering out a discordant note, Lipatti burnishes it and draws attention to its placement and how it is subsequently resolved. The chorale of the Adagio religioso of the Bartok Third Concerto is a stunning example, as chords reveal themselves to be clusters of tone vibrations (“music in its purest form”), each with its own particular flavour, colour, and message. The Third Sonata of Enescu, a work of extraordinary complexity, receives a stunning interpretation in which Lipatti is able to rapidly shift soundscapes to create a collage of tonal and atmospheric effects.

There is no greater recording of Dinu Lipatti than that of Ravel’s Alborada del Gracioso (it is, in fact, the only one with which he was fully satisfied), which reveals his varied tonal palette, staggering virtuosity, and miraculous interpretative genius. The rapid-fire repeated notes, bright punchiness of the chords, impossibly hair-raising graduated glissandos with spellbinding dynamic control, and orchestral sonorities make this one of the most phenomenal of all piano recordings, one which must be heard to be believed.

An inspiration

The bold and profoundly inspiring nature of Dinu Lipatti’s pianism continues to move lovers of fine piano playing the world over. There is little doubt that had he lived, he would have been universally acclaimed as one the greatest musical minds on the planet. While it is natural to wish for more performances to enjoy (and the possibility still exists – one cache of private recordings, known to have existed, went missing some years ago), we are indeed fortunate to have access to so many superb recordings which allow us to comprehend that such feats of musicality and divine inspiration are indeed possible. Kempff wrote that “all that is left for us to do is to remember the beauty of what he gave us, and to mourn.” Let us focus less on the drama of Dinu Lipatti’s life and death, and instead try to embody the qualities that his musicality represents, while continuing to enjoy the unique recordings of a prince of pianists who was a master musician, “an instrument of God.”

This revision © Mark Ainley, 2002

Header image of Lipatti at his final recital in Besançon courtesy of the Estate of Michel Meusy

Dinu Lipatti plays the Bach-Hess chorale Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring in 1947

Comments: 5

Mark,

While honoring the memory of Dinu Lipatti, I must also give you praise for your monumental work, which has opened my mind and that of many others to a life and artistry of this amazing genius!

Deepest thanks for your highly significant contribution to the piano world!

So glad that you are enjoying this and that you are a Lipatti fan!

Thanks for this great article, Mark! I was interested to see Maryla Jonas (listed as Maryla Jonasowna) among the entrants!

Glad you liked it, Tom. And YES, fascinating seeing Jonas in the Vienna listings. I included that name of hers in my recent article about her – hadn’t seen her full name written before!

[…] to prepare the Tchaikovsky and Emperor Concertos (absolutely not true – details in the Prince of Pianists article), there is the idea that he played very few concerted works. But before his death at the age of 33, […]